Time to Eat the Dogs

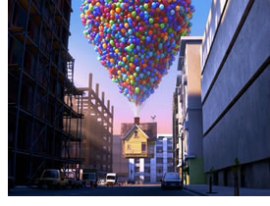

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationFilm Review: Up

Carl Fredricksen under attack by explorer Charles Muntz

Since the release of the Incredibles in 2004, Pixar has proven that it can run with grown-ups as well as the kindergarten crowd. Kid movies, after all, will always have multiple audiences. The trick is to produce stories that cohere as well as engage these different movie-goers. The Batman and Bugs Bunny of my youth did this by packing episodes with jokes, allusions, and celebrity guest stars geared to my parents. No matter, the shows had enough fights, cliff-falls, and shotgun-blasts to keep me watching.

Pixar’s strategy, however, has been more ambitious: to produce films that pull in adults by compelling stories rather than sophisticated jokes.

The Incredibles (2004), for example, broke with a tradition of scripting superhero movies as bildungsroman, coming-of-age stories for teens with mutant powers. Instead it told the story of superheroes as they are getting soft, wrestling with the demands of family life, middle age, and lost ambitions. While there are plenty of explosions and chase sequences, the real action of The Incredibles is in the livingroom, when Bob Parr (Mr Incredible) spars with his wife Helen (Elastigirl) about life’s priorities.

The Incredibles (2004)

Up boasts no superheroes or spandex, but it follows The Incredibles‘ lead by creating a protagonist, Carl Fredricksen (Ed Asner), widower and would-be adventurer, who has seen brighter days. When we meet Carl, he is grieving the loss of his wife Ellie (Ellie Docter). After a court pressures him to sell his house and enter a retirement community, he uses his balloon expertise to turn his Victorian house into a helium dirigible, sailing aloft and out of reach of contractors and nursing home attendants.

He decides to steer his craft south, towards the mythic South American land of Paradise Falls, a place he dreamed of visiting with Ellie since they formed an adventure club as kids. Only after lifting off does Carl realize that he has a passenger, Russell (Jordan Nagai), a Wilderness Explorer trying to earn an “Assisting the Elderly” merit badge.

Russell

What inspires me to write about Up here? Because the film is about exploration in the many senses of the word. From its opening shot, Up creates a backstory for Paradise Falls, a lost world which was explored by wealthy adventurer Charles Muntz (Christopher Plumber) in his dirigible, The Spirit of Adventure. Muntz returns claiming discovery of a large flightless bird, meeting with ridicule. With no proof of his discovery, he is stripped of his membership in the National Explorer’s Club, and leaves on The Spirit of Adventure (with a large pack of dogs) vowing to return once he has proven his claim to the world.

Charles Muntz, explorer of Paradise Falls

Muntz’s exploration of South America borrows much from Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1912 book, The Lost World, which also tells the story of a South American expedition (led by Dr. Challenger) who is ridiculed for claiming the discovery of living dinosaurs.

Yet as a wealthy explorer with a keen sense of technology, Muntz also resembles Howard Hughes, piloting the H-4 Hercules (Spruce Goose) in 1947, and Walter Wellman, who steered the dirigible America toward the North Pole in 1906. He also reminds me of Frederick Cook, whose claims of discovering the North Pole in 1909 eventually brought about public ridicule and expulsion from the Explorers Club the following year. (As for Muntz’s dogs, trained to perform human tasks and provided the power of speech, I couldn’t help but think of The Island of Dr. Moreau by H. G. Wells).

Walter Wellman aboard America

As for the giant flightless bird of Paradise Falls (named “Kevin” by Russell), it could be an allusion to Doyle’s dinosaur, but it also made me of the most famous description of a South American flightless bird, Charles Darwin’s discovery of the Rhea in 1833, a find that had serious implications for his theory of evolution.

Kevin, flightless bird of Paradise Falls

Rhea Darwinii

More compelling than these historical and literary allusions, however, are the deeper questions Up raises about the idea of exploration. As children, Carl and Ellie bonded over the idea of exploring Paradise Falls, a dream that was never realized during Ellie’s lifetime. It fuels Carl’s quest to reach the mythic locale after her death. Yet once he reaches the Falls, Carl opens up Ellie’s childhood “My Adventures” scrapbook to find that the pages after “Paradise Falls” are not empty, but filled with pictures of Carl and Ellie through the happy years of their marriage. Adventure – Ellie knows – is where you find it, and discovery, as William Goetzmann points out in Exploration and Empire, is almost always a question of re-discovery, finding new things in places already traveled.

Ellie and Carl

Most of all, Carl’s insight into the idea of adventure reminded me of Philip Carey, protagonist of Somerset Maughm’s novel Of Human Bondage (1915). Although Carey nurtured a lifelong dream to travel, he eventually decides to shelve this plan when he falls in love, seeing a different path to discovery:

What did he care for Spain and its cities, Cordova, Toledo, Leon; what to him were the pagodas of Burmah and the lagoons of the South Sea Islands?…He had lived always in the future, and the present always, always had slipped through his fingers. His ideals? He thought of his desire to make a design, intricate and beautiful, out of the myriad, meaningless facts of life: had he not seen also that the simplest pattern, that in which a man was born, worked, married, had children, and died, was likewise the most perfect?

Charles Muntz is the most traveled character of Up. He is also the least enlightened by his travels, scarcely touched by his experiences of Paradise Falls except for his obsessive quest with finding the flightless bird. Ellie, by contrast, never leaves the suburbs and the zoo where she works. But she understands that exploration is a state of mind as much as a plan of action, an experience that does not require talking dogs or dirigibles.

Book Review: Science and Empire in the Atlantic World

JAMES DELBOURGO and NICHOLAS DEW (eds.), Science and Empire in the Atlantic World. New York: Routledge, 2008. Pp. xiv + 365. ISBN 978-0-415-96127-1. £18.99 (paperback).

Maybe I shouldn’t read too much into titles, but Science and Empire in the Atlantic World caught my attention. At first glance, it seemed a strange choice of words since “science and empire” has become a common, almost clichéd, phrase in the history of science and science technology studies (STS). The phrase took hold in the 1970s when Marxist scholarship revealed the exploitative functions of imperial science and gained inspiration from other critiques such as Edward Said’s Orientalism in 1978.

By the 1980s, books and articles containing “science” and “empire” blossomed in the scholarly press. Yet the phrase has since witnessed a slow decline, as scholars have grown uneasy with portrayals of colonial science as a hegemonic expression of European power. Replacement terms tend to emphasize the reciprocal relationships in the production of science. Most notable among these is “Atlantic World,” a term that now races like a forest fire through history of science titles, probably due to Bernard Bailyn’s influential Seminar in the History of the Atlantic World which he instituted at Harvard in 1995. Why, then, marry “Science and Empire” with “Atlantic World” together in one title?

Bernard Bailyn

The answer comes from the function of “empire” within this edited collection. All twelve essays here challenge empire, or more precisely, an imperial top-down model of science in describing the Atlantic World. The “Empire” of the title, in other words, does not represent a historic process to be revealed, but a historiographic concept to be critiqued, a goal that Dew and Delbourgo accomplish with devastating efficiency. By focusing on famous “heroic narratives of discovery” (5) Delbourgo and Dew argue, studies of imperial science have missed the day-to-day activities which shaped the study of nature in the Atlantic World. In other words, historians of science (including me) have grown too comfortable thinking of Atlantic science through the image of a sextant-wielding Baron von Humboldt.

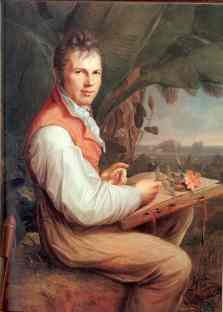

Alexander von Humboldt

As Science and Empire demonstrates, knowledge of the Atlantic World depended upon the labors of far lesser-known figures: sailors, surgeon-barbers, Creole collectors, and diasporic Africans among others. Most essays go beyond describing the actions of these invisible networks, connecting them with better known ones.

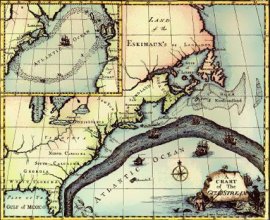

Alison Sandman, for example, explains how pilots competed with learned cosmographers to control cartographic knowledge in early modern Spain. Júnia Ferreira Furtado’s essay, focused on Brazil, shows how Dutch surgeon-barbers “broke the monopoly of erudite knowledge enjoyed by doctors,” (Furtado, 132) giving tropical medicine a pronounced, empirical tilt. Even well known figures are not what they appear. Joyce Chaplin revisits Benjamin Franklin, poster-child of elite science, to show how he relied upon the reports of sailors and sea captains in describing the Atlantic “Gulph Stream.”

Franklin Map of Gulf Stream, 1769

Taken together, the essays portray Atlantic science differently than the influential center-periphery model of science described by Bruno Latour in Science in Action (1987). Within Latour’s model, knowledge of the world starts and ends in the metropole where men of science provide the questions and instruments needed to understand nature at the edges of empire. While Latour’s system works well in describing many aspects of state-sponsored expeditions, it fails to explain other types of knowledge networks.

Bruno Latour

For one thing, Atlantic networks were unstable. As Neil Safier explains in tracing the work of French naturalist Joseph de Jussieu, acquiring and transmitting information was a precarious business. “The successful circulation of information from one point in the Atlantic to another was often dependent on circumstances that could just as easily go wrong as right” (Safier, 219). The networks developed by Spanish botanical expeditions, as described by Daniela Bleichmar, were of sturdier stuff. Yet Bleichmar points out other weaknesses in the Latourian model, specifically how “periphery” is a term ill-suited to describe botanical science in the Americas: “Circulation [of information] did not resemble the flight of a boomerang, always returning to the center, but rather a more reciprocal paddle game. Every letter or shipment from one side provoked a reply from the other.” (Bleichmar, 239). While European “centers” were important – no one disputes the asymmetries in power between mother country and colonies – they were dependent upon colonial peoples’ cooperation. This was not merely a question of finding Indians and Africans to collect things. As Susan Scott Parrish and Ralph Bauer point out in essays on diasporic Africans and Native American magic, respectively, Europeans adapted indigenous knowledge systems to make sense of an occult, magical nature. If London, Paris, and Madrid operated as hubs of scientific calculation, they were centers shaped by the world wheeling around them.

With such a strong theme linking all the essays, Science and Empire does not really need section headings. I found the four offered — “Networks of Circulation,” “Writing an American Book of Nature,” “Itineraries of Collection,” and “Contested Powers” – too vague to be useful. There are fruitful subordinate themes that track across essays, such as the tension between theory and empiricism (Sandman, Bauer, Furtado, Barrera-Osorio) and environmental history and technology (Golinski, Dew, Delbourgo, and Regourd). Still this is a minor quip. Dew and Delbourgo have managed to square the circle of edited collections: bringing together a diverse set of essays to target an important historiographical issue.

This review will be published in the upcoming issue of the British Journal for the History of Science. My thanks to BJHS for permission to reprint it here.

Wild Thing

Woodwose (detail), Albrecht Durer, 1499

Whether going up mountains, down rivers, over canyons, or across the pack-ice, adventurists often express a malaise with “civilized life” back home. In the wild, the drudgeries of the mall-shopping, lawn-mowing, 401K-filing world fall away, and with them, the barriers to authentic experience. Says Mt Everest climber Stephen Venables:

Although you don’t deliberately seek an epic, you know that one day something like that might happen. When it did happen on Everest, it was harder and more prolonged and draining than anything I had ever done, but also more exhilarating than anything I had ever done. It was like a watershed. It was something I was probably never going to repeat again. [quoted in Maria Coffey, Where the Mountain Cast Its Shadow, 137]

Why does civilization make some people feel so queasy that they’d travel to the most dangerous places on earth to find relief? A common answer is that human beings are not well-adapted to the world they inhabit, that some deeply buried instinct drives us to leave our suburban ghettos and take up high-altitude mountain climbing. A related argument holds that humans are innately curious, so curious that they are impelled, like cats near washing machines, to explore at any cost.

I don’t like these explanations. No one doubts that human beings have inherited behaviors, all animals do, but humans have proven remarkably plastic as a species. Speech patterns, fashion, diet, and language all show how impressionable we are to environment, experience, and culture.

Perhaps this reveals my bias too: as a cultural historian, I tend to think of explanations that are cultural rather than biological. In this case, I am inclined to believe that explorers and adventurers find catharsis in the wild because, well, they have learned to think of such places as cathartic.

Historians such as T. J. Jackson Lears and Gail Bederman have built a strong case for this argument. Looking at a wide array of evidence from the 19th and early 20th centuries, they link the urge to return to nature with cultural events. In particular, “going native,” Primitivism, and the Arts and Crafts movement all gain popularity just as Western societies transition from agricultural to industrial economies. For Lears and Bederman, the “call of the wild” has less to do with the feral impulses of the human psyche, and more to do with the disorienting world of the industrial city.

Tarzan of the Apes (Cover), Edgar Rice Burroughs, 1912

Yet, I will admit, the “call-of-the-wild” impulse cannot be entirely explained by culture either. If we travel back in time before industrialization, we can still find a certain malaise with civilization.

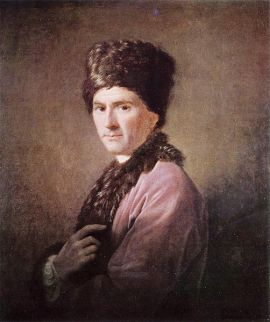

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Allan Ramsay, 1766

Living in 18th century Paris, Jean-Jacques Rousseau railed against the vanities and corruptions of civilized life. He found role models in the islands of the South Pacific where native peoples lived – so he thought – more virtuous lives closer to nature.

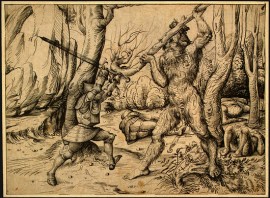

The Fight in the Forest, Hans Burgkmair, 1500 CE

We can go back even further. For Medieval Europeans the “Wildman” was a common, if legendary, figure in art and literature. Often, wildmen represented civilized men who, in the throes of madness, grief, or unrequited love, cast off everything and entered a state of nature. They reverted to savagery, acted violently, and lost their powers of speech and reason. Yet when these wildmen, by chance, were returned to the civilized world, they often emerged better for the experience: stronger of spirit and purer of heart. Such was the case with Merlin of the King Arthur legends.

Even the ancient Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, which dates to at least 2000 BCE, features the feral wild-child Enkidu, a boy raised by beasts and ignorant of all of civilization’s pleasures until seduced by the temple prostitute Shamhat. No industrial cities here.

What to make of all this? Perhaps there is something of the “call-of-the-wild” that strikes deep, beneath the reaches of culture (is there such a place?). From what we know, it appears that human beings spent most of their 125,000 year history in motion, as nomadic, itinerant tribes. Only in the last 10,000 years or so have we put down roots, developing agriculture and the foundations of complex, specialized societies. Is this restlessness a a biological shadow of our long journey as hunter-gathers? A vestigial organ of the civilized psyche? I never used to think so but I wonder.

What Kind of Explorer are You?

Robert Peary

Explorers’ narratives only get you so close to the truth. They are — like all memoirs — public documents, manuscripts that are written to be read by others. Yet they sometimes reveal things unawares. For example, Robert Peary’s 1910 book, The North Pole, is not a source you would consult to figure out if Peary really made it to the North Pole in 1909. But the book reveals much about Peary’s view of the North Pole quest and his ideals of leadership (or, to be more accurate, Peary’s views as channeled through his ghostwriter). Describing the final push across the polar pack ice in April 1909, Peary states:

This was the time for which I had reserved all my energies, the time for which I had worked for twenty-two years, for which I had lived the simple life and trained myself as for a race. In spite of my years, I felt fit for the demands of the coming days and was eager to be on the trail. As for my party, my equipment, and my supplies, they were perfect beyond my most sanguine dreams of earlier years. My party might be regarded as an ideal which had now come to realization-as loyal and responsive to my will as the fingers of my right hand. [Peary, North Pole, 270-271]

Peary’s view of his expedition “as for a race” is telling. Seeing the North Pole as the finish line in a contest rather than a region to be investigated, Peary tended to look at other explorers as rival contestants rather than colleagues or collaborators.

Peary’s view of his team as “fingers” is also revealing. It shows that Peary thought of leadership as a something dictated from the top. Teams should not exhibit independence or creative judgment, any more than fingers should challenge the mind that directs them.

While Peary’s attitudes were common among explorers, they were not universal. Alexander von Humboldt used his expedition narrative to give voice to peoples often omitted in travel literature, in particular, the Spanish and indigenous Americans who made his researches possible.

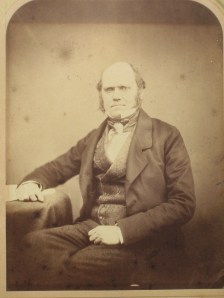

Charles Darwin

Explorer-scientists Charles Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace had good reason to feel competitive: both arrived at the theory of natural selection independently. Yet while Darwin learned of Wallace’s discovery with a certain amount of gloom, he co-reported Wallace’s work with his own. Wallace, for his part, upheld the priority of Darwin’s claim. Both men remained on good terms.

Is it your field of work that determines your approach to your peers and employees? Or other factors — class, family, work culture, personality? As I worked on my dissertation, I remember looking warily at works that approached my topic too closely. While some of these works ultimately proved helpful, they seemed dangerous at first: objects just below the waterline which might force me to change course, or worse, send my thesis to the bottom.

Yet graduate school was also a time of generous acts. We grad students kept an eye out for one another: writing down citations for each other, photocopying sources, drinking beer, listening to bad practice speeches.

Now I’m fortunate to belong to a community of generous peers: people I seek out for advice, to read early drafts, recommend books, or suggest lines of thought. These are not the only ways to approach life in the Academy – I know of a few Pearys in the field – but fortunately I see them only at some distance, marking out territory and planting flags.

The Myth of the Popular Audience

Every year I attend two or three academic conferences, mostly to keep up with friends and sneak-preview new research. Usually the best material (about friends and research) emerges from conversations in bars and hotel lobbies rather than in the faux-walled conference rooms where panelists deliver their papers. I know many colleagues who avoid the panels all together, afraid of being caught in a boring session from which they cannot (politely) escape.

Why is this? Most of the historians I know are diligent and innovative teachers, people who care about communicating with their students, who allow a great deal of back and forth in the classroom. But something strange happens when they go to conferences. Suddenly the vibrant professor is transformed into the paper-reading scholastic, delivering his/her monotone lecture as if s/he were a medieval instructor in front of young, suffering novitiates.

It makes me think that we overstate the divide between scholarly and popular audiences. Is the public all that different from the Academy in what it wants from a lecture? I want to hear talks that are well developed and delivered, talks that do not assume too much about my knowledge of the subject, talks that keep to their allotted time, talks that make a point. Isn’t this what everyone wants?

If academic and popular audiences are more similar than we think, perhaps we should also reconsider our assumptions about lecture content. Academics often make distinctions about subjects appropriate for their peers and those appropriate for everyone else. Sometimes these distinctions are warranted, particularly for talks that require a lot of theoretical knowledge at the outset. But theory is not the Iron Curtain separating scholars from public that we make it out to be. Often a quick tutorial in theory can be developed within the talk if the point is important enough.

My experience giving public lectures over the past two months have convinced me of this. While I have had to limit some of the details of my work, the structure and arguments of my talks has closely followed my scholarly writings. My talks begin with anecdote, some context, an argument, and then pieces of evidence to defend the argument. They end with a short conclusion about “why all of this matters.” Overall, I’ve gotten a good response.

What would happen if academics wrote papers for their peers as if they were addressing the general public?

Maybe things are already getting better. In the last conference I attended — the History of Science Society Annual Meeting in Pittsburgh — the papers were terrific. I chaired a panel that was focused and snappy. Everyone used images to illustrate their points. The panels I attended held their own against the meetings of peers in bars and lobbies…except, perhaps, for the drinks.