Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationArchive for Film Review

When the World Thought Tarzan Was Real

Before the vine-swinging gets underway in the latest film version of Edgar Rice Burrough’s story about a white child brought up by apes, we might remember that for years before the 1912 debut of Tarzan of the Apes in the All-Story Magazine, Americans and Europeans had been hearing stories of white men going native in Africa, not just in adventure fiction, but in explorers’ reports, newspaper accounts, and scientific journals. It wasn’t just orphaned aristocrats that were going missing, but entire white communities. While exploring East Africa in 1876, five years after his famous meeting with David Livingstone, Henry Morton Stanley encountered some Africans whose light complexion and European features aroused his curiosity “to the highest pitch.” They came from the slopes of Gambaragara, a snow-capped mountain west of Lake Victoria. That such a towering range existed in the heart of equatorial Africa was astonishing enough. “But what gives it peculiar interest,” Stanley wrote, “is that on its cold and lonely top dwell a people of an entirely distinct race, being white, like Europeans.” Stanley’s claim caused a sensation. In the months ahead, it was reported all over the world.

Other explorers brought home similar stories. In 1904, University of Chicago anthropologist Frederick Starr brought back nine hundred feet of motion picture film to document the Ainu of Hokkaido as the “aboriginal Caucasian inhabitants of Japan.” The same year that Tarzan came to press in 1912, Canadian anthropologist Vilhjalmur Stefansson returned from the Arctic reporting the discovery of “Blond Eskimos” who behaved like the Inuit but looked “like sunburned, but naturally fair Scandinavians.” A few years later, the American entrepreneur Richard Marsh returned to Washington from an expedition to Panama where he reported the discovery of “White Indians.”

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

Scientists sifted through the reports of these anomalous encounters— flaxen-haired Indians, blue-eyed Inuit, round-eyed Japanese— in hopes of connecting the dots of racial geography to form a picture of the white racial past. Out of these efforts came a theory, the Hamitic Hypothesis –named after Ham, the cursed son of Noah from Genesis 9– positing that the world’s light-complexioned indigenes were the result of an ancient Caucasian invasion from Central Asia. As it turns out, none of these white tribes turned out to be white, at least in the racial sense of the term intended by explorers. The “White Indians” of Panama were albinos, the Ainu of Japan and the “Blond Eskimos” of Victoria Island descended from ethnic groups distinct from the general population. Henry Morton Stanley’s “white race of Gambaragara” remains a mystery, but may have been a population of light-skinned East Africans who lived in the rainforests of the Ruwenzori Mountains.

Yet the legacy of these discoveries had profound consequences for the world, especially for the people of Africa. In the existence of white tribes, Europeans found justification for their conquest and colonization of the world. If the European race had its own long history on the continent, it followed that the Europeans who followed Stanley into Africa were not settling, but re-settling, lands that had been conquered by fair-skinned invaders centuries before. As such, the white-complexioned Gambaragarans provided supporting evidence to an argument that redefined Africa’s past, and more importantly set its course for the century ahead.

None of this should be laid at the door of Edgar Rice Burroughs. He was a pencil sharpener wholesaler when he wrote Tarzan of the Apes. His novel reflected, rather than directed, the events of his age. Yet beneath its fantastic plot lay a thought experiment. How would an Englishman without his tweeds, gun, and Oxford degree size up alongside the African? How would a viscount or earl perform once the veneer of polite society had been stripped away? The answer: pretty awesome. This is the racial fantasy that, despite its many revisions and movie incarnations, clings Jane-like to Tarzan as he swings through the twenty-first century.

For more on this subject, read (shameless plug) my book:

The Lost White Tribe: Explorers, Scientists, and the Theory that Changed a Continent

The Myth of Pure Experience

The Hero’s Journey

The hero’s journey is a story common to all human cultures. While this story varies from from place to place and era to era, there are deep structural similarities among its forms. So common were these basic structural elements that comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell called the hero story a “monomyth.”

The story has a structure that we recognize in Bible stories and big-screen films alike: a hero departs the comforts of the known world on a quest. She endures physical and emotional trials, gains wisdom, and returns home to impart lessons learned on the journey.

Campbell’s eagerness (following Jung’s) to reduce all stories to basic structures makes me a little uneasy. (Can we really blueprint all human art forms?) But in the case of the hero story, I think he was on to something. The power of the journey story does appear to have almost universal expression and a common lesson also: that we gain knowledge by our encounter with the unknown and its perils.

That doesn’t mean, however, that the monomyth is monolithic. I see two important variants: some heroes gain knowledge in their quest that adds to things they already know (e.g. Moses and Jesus). Others discard their possessions and beliefs in order to find the truth (e.g. Plato’s prisoner of the cave, Siddhārtha Gautama, and St Francis of Assisi).

Since the late 1700s, the latter variant of the hero monomyth — that one must escape civilization in order to find oneself — has gained a strong foothold in the West. Although the idea that civilization corrupts is an old one, it has blossomed with the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and others.

In its most extreme form, the escape-civilization-to-find-enlightenment myth suggests that the traveler or explorer gains wisdom only when civilization is burned away by extreme experience. As climber Robert Dunn put it in 1907: explorers were “men with the masks of civilization torn off.”

Or as climber David Breashears expressed it a century later:

The idea is that all the artifice that we carry with us in life, the persona that we project—all that’s stripped away at altitude. Thin air, hypoxia—people are tremendously sleep-deprived on Everest, they’re incredibly exhausted, and they’re hungry and dehydrated. They are in a very altered state. And then at a moment of great vulnerability a storm hits. At that moment you become the person you are. You are no longer capable of mustering all this artifice. The way I characterize it, you either offer help or you cry for help.

But if the journey does its wisdom-building work by tearing off the mask of civilization, by stripping away artifice, we are left with this question:

What’s underneath the mask?

Dunn and Breashears imply that the true self is revealed: the intense experiences of the journey shear the subject of culture and its trappings. This is a comforting idea at first glance because it presumes that

1) you can find yourself by setting out on an exceptionally difficult adventure.

2) your problems are the result of your culture rather than your essential nature.

This reminds me a lot of John Locke who also believed that you could neatly separate the original self from one imprinted by civilization. In An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690), Locke argued that human beings begin their journey tabula rasa — as blank slates — waiting to be shaped by experience. The Lockian newborn was a human TiVo pulled from its styrofoam packing, waiting to be filled by sounds and images that would give it its special identity.

I doubt that Dunn or Breashears believe the journey can return the explorer to the perfect self of the infant. I expect they see the perilous journey as a way of re-booting the TiVo rather than wiping it clean, clear out old programming to make space for new material.

The Cult of New Experience

The important point here is this: those who think of the self as something that can be purged of culture, like a psychological master cleanse, tend to weight the power of new experience over the power of reason or ideas, to prefer the bungee jump over the writer’s retreat. In their view, traditional ideas impede our understanding rather than advance it. To access the new, we need to leave our old selves — like a pair of flip-flops — at the door.

Perhaps this obsession with the power of experience explains why so many travelers and explorer seem concerned with having “authentic” experience rather than ones they see as packaged, hybrid, or touristy. In the traveler’s search for the truly different, she must avoid experiences that carry the whiff of world left behind. She avoids the McDonalds in Karachi. She turns down the tour bus to the pyramids. She resists the urge to text-message home from the summit of Everest.

But is our faith in the uber-experience wise? Can we peel away our culture like the rind off an orange? Closer inspection shows how much culture enters the flesh, shapes us, makes us. Humans have an innate form, of course, but its a form that cannot function without an environment. So speaking about one without the other is like asking “Which do plants need more: water or light?”

Before we make pure experience the holy grail of the self-knowledge, then, we need to pay closer attention to the way humans think about these experiences.

First, authentic is a rather squishy concept. Cultures routinely borrow and import what they need from other cultures. For example, in Eat Pray Love, Elizabeth Gilbert discovers herself in part through her ecstatic encounter with Italy. Italy’s authenticity is expressed through its foods: it is a place of fried zucchini blossoms and sizzling Margarita pizza. Yet the core ingredients of these foods — zucchini and tomatoes — are foreign to Italy. They are both New World species, brought back to Europe and incorporated into Italian cooking in the 19th century. What is authentically Italian experience for Gilbert was, two centuries earlier, suspiciously foreign and non-Italian.

Second, experience itself is never pure, never unmediated (as I wrote about in my recent post about Moscow). Even those experiences which seen so expressly sensory — the joy of food, sex, art — feel different according to our beliefs about them. In his book, How Pleasure Works: The New Science of Why We Like What We Like, Paul Bloom explodes the myth of pure experience:

What matters most is not the world as it appears according to our senses. Rather, the enjoyment we get from something derives from what we think that thing is. This is true of intellectual pleasures, such as the appreciation of paintings and stories, and also for pleasures that seem simpler, such as the satisfaction of hunger and lust. For a painting, it matters who the artist was; for a story whether it is truth or fiction; for a steak we care about what sort of animal it came from; for sex, we care about who we think our sexual partner really is [xii]

Can we apply Bloom’s analysis of pleasure to the explorer’s experience of pain? Does the ascent up Everest gain meaning because of the pure experience of frostbite and hypoxia? Or does it matter more that the climber is enduring such pain on the slopes of the world’s tallest mountain? The mask of civilization is not something that the climber rips away. It’s the reason the climber is there in the first place.

Film Review: Avatar

As I went to see Avatar last week, I felt resigned. It had all of the predictors of a bad movie.

First, it cost half a billion dollars to make. This may seem promising. What film wouldn’t benefit from vast sums to improve cast, scripts, and special effects? Yet big budgets are usually the death of good films because studios become obsessed with recovering their investments. The question of “how do we make a good film” becomes eclipsed by “how do we make a film that brings in 500 million dollars of audience?” The recipe for this is well known: find big name actors, put them in a romance story which doubles as an action film, and sprinkle liberally with special effects. Toy merchandising helps too.

Second, Avatar was developed as a 3-D computer graphics film, only occasionally including scenes with human actors. While CGI has revolutionized film-making, it has often been used indiscriminately, creating scenes that are ill-conceived, implausible, or – with hundreds of moving points of animation – impossible to watch. George Lucas is the poster-child for CGI abuse. The coherence and narrative tension of the original Star Wars series was no where to be found in the prequel episodes of the last decade, as the demands of the blue-screen eclipsed plot, drama, and character development.

Third, Avatar follows two of the most cliched genres in films: it is coming-of-age movie, a bildungsroman in space, and a “going native” story where the lead, Jake Sully (Sam Worthington), a paraplegic marine, finds meaning in life by becoming a member of “primitive” tribe, the Na’vi on the planet of Pandora. This feat is made possible by the creation of a Na’vi avatar that Sully inhabits for most of the film. (To see how easily Avatar maps on to other ‘going native’ films, see these mashups here and here of Avatar & Disney’s Pocahontas)

So I was surprised that I really like this movie. The millions of dollars used in production and marketing have not corrupted the soul of Avatar. Credit for this goes to director, James Cameron, who has proven capable of directing massively expensive, CGI intensive films (Terminator, Aliens, and Titanic) without surrendering plot and coherence.

As for the CGI effects, they are stunning to behold. The planet of Pandora is rendered with brilliant color and movement, texture and imagination. The ten-foot tall Na’vi – who in the real universe would already have been recruited for the NBA, move with all of the grace of real humans, or rather, humanoids. After a few minutes, I forgot I was watching CGI, or more accurately, I forgot about the distinction between CGI and “real life.” This is a clever effect since the viewer is, in a sense, recapitulating Sully’s experience with his avatar.

Most importantly, the story of Jake Sully’s assimilation into the world of the Na’vi, while predictable, is not mawkish. It isn’t hard to believe that a man who has lost the use of his legs, spent six years in space, and no longer functions within the world of the Marines, would find running and flying through wilds of Pandora exhilarating.

Indeed, it is the idea of the avatar that keeps this ‘going native’ story interesting. Other films in this genre, from Apocalypse Now to Dances With Wolves, follow men as they cut themselves off from the world left behind. By contrast, Avatar follows Sully as he moves back and forth between worlds: his avatar existence with the Na’vi and his human existence in base camp. How does one go native if there is constant access to the world one is leaving? The moral conflict which results provides Avatar with much of its narrative tension.

Finally, Avatar proves three-dimensional in another sense, by taking this theme of remote connection beyond the story of Sully and the Na’vi. The Marines on Pandora have found their own avatars of sorts, in the weaponized “Amplified Mobility Platform” or AMP (which bears more than a passing resemblance to the cargo loader operated by Sigourney Weaver in Aliens).

The Na’vi, on the other hand, are able to link, through neuro-chemical connections to other beings on Pandora. Indeed, the planet itself operates as an organic neural network. Avatars, in other words, have many incarnations and, in their most developed states, begin to emulate a kind of Gaia or world-soul. At what point does neural connectivity cross the line into spirituality? While Avatar sometimes crosses the line into a preachy environmentalism, the bigger questions that it raises make it worth the ride.

Film Review: Up

Carl Fredricksen under attack by explorer Charles Muntz

Since the release of the Incredibles in 2004, Pixar has proven that it can run with grown-ups as well as the kindergarten crowd. Kid movies, after all, will always have multiple audiences. The trick is to produce stories that cohere as well as engage these different movie-goers. The Batman and Bugs Bunny of my youth did this by packing episodes with jokes, allusions, and celebrity guest stars geared to my parents. No matter, the shows had enough fights, cliff-falls, and shotgun-blasts to keep me watching.

Pixar’s strategy, however, has been more ambitious: to produce films that pull in adults by compelling stories rather than sophisticated jokes.

The Incredibles (2004), for example, broke with a tradition of scripting superhero movies as bildungsroman, coming-of-age stories for teens with mutant powers. Instead it told the story of superheroes as they are getting soft, wrestling with the demands of family life, middle age, and lost ambitions. While there are plenty of explosions and chase sequences, the real action of The Incredibles is in the livingroom, when Bob Parr (Mr Incredible) spars with his wife Helen (Elastigirl) about life’s priorities.

The Incredibles (2004)

Up boasts no superheroes or spandex, but it follows The Incredibles‘ lead by creating a protagonist, Carl Fredricksen (Ed Asner), widower and would-be adventurer, who has seen brighter days. When we meet Carl, he is grieving the loss of his wife Ellie (Ellie Docter). After a court pressures him to sell his house and enter a retirement community, he uses his balloon expertise to turn his Victorian house into a helium dirigible, sailing aloft and out of reach of contractors and nursing home attendants.

He decides to steer his craft south, towards the mythic South American land of Paradise Falls, a place he dreamed of visiting with Ellie since they formed an adventure club as kids. Only after lifting off does Carl realize that he has a passenger, Russell (Jordan Nagai), a Wilderness Explorer trying to earn an “Assisting the Elderly” merit badge.

Russell

What inspires me to write about Up here? Because the film is about exploration in the many senses of the word. From its opening shot, Up creates a backstory for Paradise Falls, a lost world which was explored by wealthy adventurer Charles Muntz (Christopher Plumber) in his dirigible, The Spirit of Adventure. Muntz returns claiming discovery of a large flightless bird, meeting with ridicule. With no proof of his discovery, he is stripped of his membership in the National Explorer’s Club, and leaves on The Spirit of Adventure (with a large pack of dogs) vowing to return once he has proven his claim to the world.

Charles Muntz, explorer of Paradise Falls

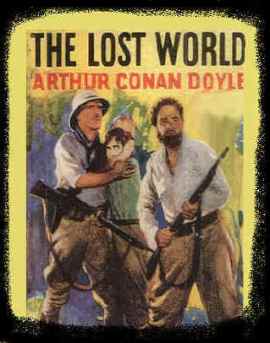

Muntz’s exploration of South America borrows much from Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1912 book, The Lost World, which also tells the story of a South American expedition (led by Dr. Challenger) who is ridiculed for claiming the discovery of living dinosaurs.

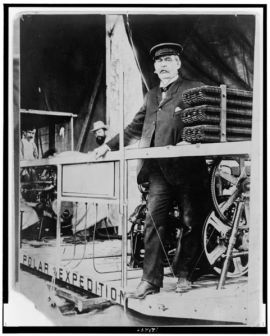

Yet as a wealthy explorer with a keen sense of technology, Muntz also resembles Howard Hughes, piloting the H-4 Hercules (Spruce Goose) in 1947, and Walter Wellman, who steered the dirigible America toward the North Pole in 1906. He also reminds me of Frederick Cook, whose claims of discovering the North Pole in 1909 eventually brought about public ridicule and expulsion from the Explorers Club the following year. (As for Muntz’s dogs, trained to perform human tasks and provided the power of speech, I couldn’t help but think of The Island of Dr. Moreau by H. G. Wells).

Walter Wellman aboard America

As for the giant flightless bird of Paradise Falls (named “Kevin” by Russell), it could be an allusion to Doyle’s dinosaur, but it also made me of the most famous description of a South American flightless bird, Charles Darwin’s discovery of the Rhea in 1833, a find that had serious implications for his theory of evolution.

Kevin, flightless bird of Paradise Falls

Rhea Darwinii

More compelling than these historical and literary allusions, however, are the deeper questions Up raises about the idea of exploration. As children, Carl and Ellie bonded over the idea of exploring Paradise Falls, a dream that was never realized during Ellie’s lifetime. It fuels Carl’s quest to reach the mythic locale after her death. Yet once he reaches the Falls, Carl opens up Ellie’s childhood “My Adventures” scrapbook to find that the pages after “Paradise Falls” are not empty, but filled with pictures of Carl and Ellie through the happy years of their marriage. Adventure – Ellie knows – is where you find it, and discovery, as William Goetzmann points out in Exploration and Empire, is almost always a question of re-discovery, finding new things in places already traveled.

Ellie and Carl

Most of all, Carl’s insight into the idea of adventure reminded me of Philip Carey, protagonist of Somerset Maughm’s novel Of Human Bondage (1915). Although Carey nurtured a lifelong dream to travel, he eventually decides to shelve this plan when he falls in love, seeing a different path to discovery:

What did he care for Spain and its cities, Cordova, Toledo, Leon; what to him were the pagodas of Burmah and the lagoons of the South Sea Islands?…He had lived always in the future, and the present always, always had slipped through his fingers. His ideals? He thought of his desire to make a design, intricate and beautiful, out of the myriad, meaningless facts of life: had he not seen also that the simplest pattern, that in which a man was born, worked, married, had children, and died, was likewise the most perfect?

Charles Muntz is the most traveled character of Up. He is also the least enlightened by his travels, scarcely touched by his experiences of Paradise Falls except for his obsessive quest with finding the flightless bird. Ellie, by contrast, never leaves the suburbs and the zoo where she works. But she understands that exploration is a state of mind as much as a plan of action, an experience that does not require talking dogs or dirigibles.