Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationFilm Review: Avatar

As I went to see Avatar last week, I felt resigned. It had all of the predictors of a bad movie.

First, it cost half a billion dollars to make. This may seem promising. What film wouldn’t benefit from vast sums to improve cast, scripts, and special effects? Yet big budgets are usually the death of good films because studios become obsessed with recovering their investments. The question of “how do we make a good film” becomes eclipsed by “how do we make a film that brings in 500 million dollars of audience?” The recipe for this is well known: find big name actors, put them in a romance story which doubles as an action film, and sprinkle liberally with special effects. Toy merchandising helps too.

Second, Avatar was developed as a 3-D computer graphics film, only occasionally including scenes with human actors. While CGI has revolutionized film-making, it has often been used indiscriminately, creating scenes that are ill-conceived, implausible, or – with hundreds of moving points of animation – impossible to watch. George Lucas is the poster-child for CGI abuse. The coherence and narrative tension of the original Star Wars series was no where to be found in the prequel episodes of the last decade, as the demands of the blue-screen eclipsed plot, drama, and character development.

Third, Avatar follows two of the most cliched genres in films: it is coming-of-age movie, a bildungsroman in space, and a “going native” story where the lead, Jake Sully (Sam Worthington), a paraplegic marine, finds meaning in life by becoming a member of “primitive” tribe, the Na’vi on the planet of Pandora. This feat is made possible by the creation of a Na’vi avatar that Sully inhabits for most of the film. (To see how easily Avatar maps on to other ‘going native’ films, see these mashups here and here of Avatar & Disney’s Pocahontas)

So I was surprised that I really like this movie. The millions of dollars used in production and marketing have not corrupted the soul of Avatar. Credit for this goes to director, James Cameron, who has proven capable of directing massively expensive, CGI intensive films (Terminator, Aliens, and Titanic) without surrendering plot and coherence.

As for the CGI effects, they are stunning to behold. The planet of Pandora is rendered with brilliant color and movement, texture and imagination. The ten-foot tall Na’vi – who in the real universe would already have been recruited for the NBA, move with all of the grace of real humans, or rather, humanoids. After a few minutes, I forgot I was watching CGI, or more accurately, I forgot about the distinction between CGI and “real life.” This is a clever effect since the viewer is, in a sense, recapitulating Sully’s experience with his avatar.

Most importantly, the story of Jake Sully’s assimilation into the world of the Na’vi, while predictable, is not mawkish. It isn’t hard to believe that a man who has lost the use of his legs, spent six years in space, and no longer functions within the world of the Marines, would find running and flying through wilds of Pandora exhilarating.

Indeed, it is the idea of the avatar that keeps this ‘going native’ story interesting. Other films in this genre, from Apocalypse Now to Dances With Wolves, follow men as they cut themselves off from the world left behind. By contrast, Avatar follows Sully as he moves back and forth between worlds: his avatar existence with the Na’vi and his human existence in base camp. How does one go native if there is constant access to the world one is leaving? The moral conflict which results provides Avatar with much of its narrative tension.

Finally, Avatar proves three-dimensional in another sense, by taking this theme of remote connection beyond the story of Sully and the Na’vi. The Marines on Pandora have found their own avatars of sorts, in the weaponized “Amplified Mobility Platform” or AMP (which bears more than a passing resemblance to the cargo loader operated by Sigourney Weaver in Aliens).

The Na’vi, on the other hand, are able to link, through neuro-chemical connections to other beings on Pandora. Indeed, the planet itself operates as an organic neural network. Avatars, in other words, have many incarnations and, in their most developed states, begin to emulate a kind of Gaia or world-soul. At what point does neural connectivity cross the line into spirituality? While Avatar sometimes crosses the line into a preachy environmentalism, the bigger questions that it raises make it worth the ride.

Furr

Despite their endangered status, wolves still roam freely in the world of myths and fables. She-wolf Lupa became the patriotic mother of Rome when she wet-nursed Romulus and Remus. The wolves of European fairy tales, on the other hand, were destroyers, the natural enemy of pigs, sheep, children, and near-sighted grandmothers.

Late 20th-century portrayals of wolves show a softer side: Kevin Costner’s companion Two Socks is the playful title figure of Dances With Wolves (1990). The wolf pack of Never Cry Wolf (1983) act as teachers to Farley Mowat (played by Charles Martin Smith). Indeed, the image of the wolf seems to improve as the number of real wolves diminish.

In this, the wolf of the western imagination seems to be following a path taken by others, namely American Indians, who were often portrayed as blood-thirsty and menacing in the 18th and early 19th centuries, but eventual found redemption in the eyes of white Americans as “children of nature” in the late 1800s. It was at this time that real Indians were no longer perceived as a threat to Euro-American expansion.

Yet while Indian and Wolf have both become symbols of nature, I wonder: do these symbols function in similar ways? What about other symbols of nature such as wildman that I wrote about in an earlier post? This was my question as I listed to the song “Furr” by Blizten Trapper:

When I was only 17

I could hear the angels whispering

So I drove into the woods

and wandered aimlessly about

Until I heard my mother shouting through the fog

It turned out to be the howling of a dog

Or a wolf to be exact

the sound sent shivers down my back

But I was drawn into the pack and before long

They allowed me to join in and sing their song

So from the cliffs and highest hill

We would gladly get our fill

Howling endlessly and shrilly at the dawn

And I lost the taste for judging right from wrong

For my flesh had turned to fur

And my thoughts, they surely were

Turned to instinct and obedience to God.

You can wear your fur

like a river on fire

But you better be sure

if you’re makin’ God a liar

I’m a rattlesnake, Babe,

I’m like fuel on fire

So if you’re gonna’ get made,

Don’t be afraid of what you’ve learned

On the day that I turned 23,

I was curled up underneath a dogwood tree

When suddenly a girl with skin the color of a pearl

She wandered aimlessly, but she didn’t seem to see

She was listening for the angels just like me

So I stood and looked about

I brushed the leaves off of my snout

And then I heard my mother shouting through the trees

You should have seen that girl go shaky at the knees

So I took her by the arm

We settled down upon a farm

And raised our children up as gently as you please.

And now my fur has turned to skin

And I’ve been quickly ushered in

To a world that I confess I do not know

But I still dream of running careless through the snow

And through the howling winds that blow,

Across the ancient distant flow,

It fill our bodies up like water till we know.

Stories of wolf-human transformation have a rich history, dating back thousands of years, to the Greek myth of Lycaon who became a wolf after eating human flesh, and extending to Asian and American cultures, such as the Navajo legends of the Mai-cob. (For an excellent treatment of wolves in Asia, see Brett Walker’s book, The Lost Wolves of Japan)

But these transformations also seem to be getting softer over time. Medieval werewolves are devilish creatures, agents of terror. But 20th century werewolves are considerably less brutish, sometimes even urbane, from An American Werewolf in London to the hunky werewolves of Underworld. Blitzen Trapper’s man-wolf certainly doesn’t do the devil’s bidding. Rather he seems to be on an existential Outward Bound course. And in due time, he makes the transformation back into man rather easily, if with a bit of nostalgia for his doggy life.

I like “Furr ” a song that Bob Dylan would have written perhaps if he were taken by the spirit of Jack London. But it also makes me wonder why wolves and werewolves have become progressively de-clawed as cultural symbols, a process that extends to their symbolic cousins, vampires.

Do we feel so far removed from nature that all things feral seem alluring at a distance? Or is our desire for transformative experience so strong that we’ve made animal and demon possessions user-friendly? In this new age of shape-shifting, one does not have to lose one’s soul to visit the dark side. It might even be worth the trip. Look how far we’ve come.

Interview with Felix Driver

A Malay native from Batavia at Coepang, portrait of Mohammed Jen Jamain by Thomas Baines. Courtesy of the Royal Geographical Society

The history of exploration does not have its own departments in universities. It does not really exist as a historical sub-discipline either, at least in the way that formalized fields such as labor history, women’s history and political history do. Instead, the history of exploration is a disciplinary interloper, a subject taken up by many fields such as literary studies, anthropology, geography, and the history of science. Each brings its own unique perspective and methods. Each has its own preoccupations and biases.

All of which makes the work of Felix Driver, professor of human geography at Royal Holloway, University of London, especially important. While Driver has covered many of the meat-and-potatoes subjects in exploration: navigation, shipwrecks, and biographical subjects such as Henry Morton Stanley and David Livingstone, he has framed them in the broadest context: through the visual arts, postmodern theory, social history, and historical geography.

He is the author of many books and articles including Geography Militant: Cultures of Exploration and Empire. He is also the co-editor of Tropical Visions in an Age of Empire which came out with University of Chicago Press in 2005.

At the same time, Driver has worked to bring these subjects to the attention of the public, supervising the new Royal Geographical Society exhibition, Hidden Histories of Exploration. The exhibition, which opened on October 15, “offers a new perspective on the Society’s Collections, highlighting the role of local inhabitants and intermediaries in the history of exploration.”

Driver took some time to speak with me about the exhibition and his work on exploration.

Welcome Felix Driver.

What inspired the Hidden Histories exhibition?

A conviction that the history of exploration was about a wider, collective experience of work and imagination rather than simply a story of lone individuals fighting against the odds. The idea of ‘hidden histories’ has an innate appeal – it suggests stories that have not been heard, which have been hidden from history, waiting to be uncovered. It has already provided the RGS with a model for a series of exhibitions linking aspects of their Collections with communities in London. The Society’s strong commitment to public engagement in recent years provided an opportunity for a more research-oriented exhibition which asked a simple question: can we think about exploration differently, using these same Collections which have inspired such great stories about heroic individuals? This was a kind of experiment, in which the Collections themselves were our field site: together with Lowri Jones, a researcher on the project, we set out to explore its contours, trying to make these other histories more visible.

Hidden Histories uses RGS collections to look at “role of local peoples and intermediaries in the history of global exploration.” Those of us who study exploration get excited by this, but how do you pitch it to the general public? How do you engage the exploration buff interested only in Peary, Stanley, or Columbus?

That’s a good question. The exploration publishing industry has returned over and over to the same stories. The lives of great explorers continue to sell well, and that is one aspect of the continuing vitality of what I call our culture of exploration. Still, recent developments in the field and in popular science publishing have encouraged authors and readers to shift the focus somewhat, turning the spotlight on lesser known individuals whose experiences have been overshadowed. Consider for example the success of some terrific popular works on the theme of exploration and travel such as Robert Whitaker’s The Mapmaker’s Wife, or Matthew Kneale’s novel English Passengers, which are all about large and complex issues of language, translation, misunderstanding and exchange. That gives you a bit of hope that actually readers are looking for something new, so long as there is a good story there! Of course it is not easy – so much simpler to tread the path of our predecessors. Sometimes it requires an exploring spirit to venture further from the beaten track….

What first drew you to the history of exploration? Is there particular question or theme that guides your research? How have your interests changed over time?

What drew me first to the history of exploration was a growing realization that the subject was more important to my own academic field – geography – than my teachers in the 1970s were prepared to admit. I was interested in the worldly role and impact of geographical knowledge, socially, economically and politically. When I was at school and college, ‘relevance’ was in the air and geographers were turning their attention to questions of policy and politics. My point was that geographical knowledge has been and continued to be hugely significant in the world beyond the academic, from travel writing to military mapping, and exploration provided one way into this. There were other ways into this worldly presence, of course, and the work of my PhD supervisor Derek Gregory has had a lasting influence.

Much of my own writing has focused strongly on the long nineteenth century, partly because this was a period in which I immersed myself for my PhD and first teaching (my first post was a joint appointment in history and geography). However, I was drawn to the work of social historians – at first EP Thompson’s Making of the English Working Class, later work influenced by new models of cultural history. Partly because of my appointment on the borders of two disciplines, I found myself increasingly attracted to fields – such as Victorian studies or the history of science – that were in a sense already interdisciplinary. In both these cases, an interest in space and location has had a strong impact on the best writing in the field. Historians like Jim Secord and Dorinda Outram, as well as geographers such as David N. Livingstone and Charles Withers, taught me a lot about the ways in which ideas about exploration circulate, and why it is important to think of knowledge in practical as well as intellectual terms.

My interest in the visual culture of exploration and travel reflects the strong focus on the visual has shaped the work of geographers in this area, pre-eminently Stephen Daniels and Denis Cosgrove. My interests developed through work with James Ryan, whose book on the photographic collections of the RGS remains a seminal work. Later I worked with Luciana Martins on a project on British images of the tropical world in which we were particularly concerned with the observational skills of ordinary seamen and humble collectors rather than the grand theorists of nature. In retrospect, this project paved the way for some of the themes in the hidden histories of exploration exhibition. But this exhibition also represents a departure for me as the focus is squarely on the work of non-Europeans. There is an interesting discussion to be had here about whether turning figures like Nain Singh or Jacob Wainwright into ‘heroes’, just like Stanley or Livingstone, is the way to go. Perhaps we can’t think of exploration without heroes, and it’s a matter of re-thinking what we mean by heroism. Or perhaps we historians need to do more than ruminate on the vices and virtues of particular explorers, by considering the networks and institutions which made their voyages possible and gave them a wider significance.

In Geography Militant, you warned that scholars were focusing on exploration too much as an “imperial will-to-power” [8] ignoring the unique and contingent qualities of each expeditionary encounter. You developed this argument further in Tropical Visions in an Age of Empire. Do you think scholars are now moving away from an “empire-is-everywhere” world view? If so, what do you think we are moving towards?

This is not an original view. Many of the best known historians and literary critics writing on empire have made similar points: I am thinking of Peter Hulme, Catherine Hall and Nicholas Thomas. What I take from them is a deep sense of what colonialism and empire meant – not just at the level of trumpets and gunboats, but in the very making of our sense of ourselves and our place in the world, past and present. At the same time, I have wanted to highlight the fractured, diverse nature of the colonial experience and I have never been happy with lumpen versions of ‘colonial discourse’ which used to be advanced within some versions of postcolonial theory. This interest in difference is reflected in my interest in moments of controversy and crisis, points where the uncertainties and tensions come to the surface (as in controversies over the expeditions of Henry Morton Stanley). You can’t work on exploration for long without realizing the strong emotional pull of the subject on explorers and their publics; and the fact quite simply that they were always arguing, either with ‘armchair geographers’ (those much maligned stay-at-homes) or with their peers. If these arguments were frequently staged if not orchestrated by others, that is part of the point: these controversies were more than simply the product of disputatious personalities, they were built in to the fabric of the culture which produced them.

What’s your next project?

In recent years I have worked on a variety of smaller projects on collectors and collecting, involving everything from insects to textiles. What I would like to do next is a book on the visual culture of exploration, drawing on a wide variety of materials from sketch-books to film. Some of these materials are represented in the hidden histories exhibition, notably the sketchbooks of John Linton Palmer and the 1922 Everest film featured on the website. But there is much left to explore!

Thanks for speaking with me.

Your work focuses on many issues besides the history of exploration, including visual arts, the geography of cities, and questions of identity and empire.

The Remotest Place on Earth

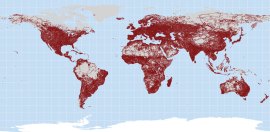

Travel times to major cities. Shipping lanes in blue. Image Credit: NewScientist

This week, NewScientist announced the remotest place on earth: 34.7°N 85.7°E, a cold, rocky spot 17,500 ft up the Tibetan Plateau. From 34.7°N 85.7°E it takes three weeks by foot to reach Lhasa or Korla.

Not that anyone has tried. No council of explorers advised NewScientist on its choice of locations. It was determined by using geographical information systems (GIS) which combined number of factors, including:

information on terrain and access to road, rail and river networks. It also consider[ed] how factors like altitude, steepness of terrain and hold-ups like border crossings slow travel.

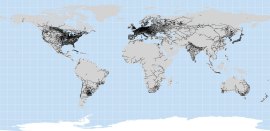

The world's roads. Image credit: NewScientist

Nineteenth century maps still occasionally showed regions of Terra Incognita. But twenty-first century maps have no blank spaces left. The NewScientist maps offer, in their measure of “most remote” a modern equivalent.

The world's railroads. Image credit: NewScientist

Finding the remotest place on earth is an interesting project. In tracing this circulation system of human movement, we see how closely it correlates to areas of wealth and industrialization. Still I wonder if human movement – specifically how long it takes to reach a major city – is the best way to measure remoteness. Today cell phones and the internet connect people in some of the world’s loneliest places. There are no roads or trains that reach the pinnacle of Everest. Yet it can be reached by cell phone, observed from base camp by telescope, viewed in three dimensions through satellite images in Google Earth.

The world's navigable rivers. Image credit: NewScientist

By contrast, there are places within the bright regions of the NewScientist map where connectivity fails. A resident of the Ninth Ward of New Orleans or Cairo’s City of the Dead are only minutes away from a web of roads, rivers, and trains. Yet how often do residents use them? In these cases, remoteness is not a matter of distance, but of culture and socio-economics. How do we measure these kinds of blank spaces on the map?

Why We Need a New History of Exploration

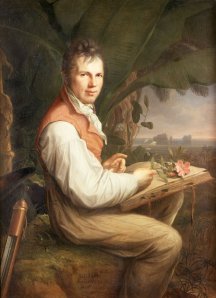

Alexander von Humboldt by Friedrich Georg Weitsch, 1806.

Today, just some announcements:

Common-Place, the online history journal, just published my article, “Why We Need a New History of Exploration.” You can read it here.

SciCafe, at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, is presenting “Darwin on Facebook: How Culture Transforms Human Evolution” a presentation by anthropologist Peter Richerson. “SciCafe features cutting-edge science, cocktails, and conversation and takes place on the first Wednesday of every month. For more information, please visit amnh.org/scicafe”

The Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) opens its new exhibition Hidden Histories of Exploration today in London. The exhibition website is worth checking out. I hope to be doing a more extensive write-up of the exhibition (and curator Felix Driver) soon.