Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationTrump’s Rough-Riding Populism

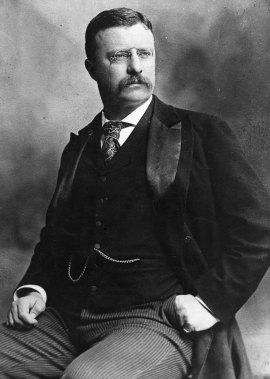

We’ve seen this before. A scion of New York – one born with a silver spoon in his mouth – becomes the GOP presidential nominee, prophesying national decline and blaring a populist tune at odds with his own party. Businessmen and politicians are rigging the system! Immigrants are weakening America! An influx of foreigners taking our jobs and creating “obstructions to the current of our national life,” he declares, urgently demanding us to “regulate our immigration by much more drastic laws.” Not all of the immigrants are bad, of course, but the “criminals, idiots, and paupers” among them must be turned back. Especially those in border areas who pose an existential threat to American language, culture, and way of life.

French-Canadian migrants, that is. “They are swarming into New England with ominous rapidity,” Theodore Roosevelt confided to a friend. The year was 1904.

There are echoes of Teddy Roosevelt in Donald Trump, just as there are echoes of the Progressive Era in today’s America. Both men championed issues ignored by the social class they arose from. Both were obsessed with their own virility. (Trump doesn’t speak softly, but boasts about his big stick). And both used race to win votes. Roosevelt worried publicly that immigration, combined with a declining Anglo-Saxon birth rate, would “supplant the old American stock.” Race suicide, as he called it, could only be stopped by curbing immigration and increasing white birth rates. This sounds a lot like the utterances of today’s Stormfront.org, “White Genocide” acolytes, and other racist rightwing groups that have applauded Trump’s statements on Muslims and Mexicans.

Yet Roosevelt differed from Trump in important ways. He was an optimist about American culture and its ability to absorb new immigrants, even as he hoped they would assimilate the culture of “old American stock.” Doom and gloom were not his métier. Though he finished his letter on the Canuck deluge by predicting that Catholicism would become “the predominant creed in several of the Puritan commonwealths” – a prospect to horrify the WASPocracy – he himself remained “a firm believer that the future will somehow bring things right in the end for our land.” Roosevelt had no intention of building walls. He needed no “I love poutine!” photo to soften his harsh views.

His fighting spirit and love of provocation notwithstanding, Roosevelt was also a seasoned politician, with the experience – as state assemblyman, Governor of New York, and vice-president of the United States — to help him move his Progressive agenda through Congress. In the end, his presidency addressed much more than race and immigration. Roosevelt lowered taxes and tariffs even as he curbed the power of monopolies. He pushed through reform legislation like the Pure Food and Drug Act. He ushered in an era of environmental conservation via the creation of National Parks, Game Preserves, and National Forests. The Rough Rider, in short, had real goals and policies, along with the will and the wherewithal to effect them. Does Trump?

Trump works the crowd at the Macon Centreplex Coliseum in Macon, Ga. (Curtis Compton/Atlanta Journal-Constitution via AP)

Finally – another irony — it’s worth noting that Roosevelt’s Progressive-Era populism fell short on a point that should give pause to those Trumpistas tempted to adopt the original Rough Rider as their patron saint: namely, that his vision for America did not include them. In the dominant view of his day, Irish, Italian, Eastern European, and French Canadian immigrants might be white in color, but not in “stock.” The uneducated and underemployed whites who stand at the center of the Trump’s world stood marginalized and often reviled in Roosevelt’s – the demographic problem, not the solution. As Roosevelt the historian –yes, he was that, too—knew well, the more times remain the same, the more they change.

When the World Thought Tarzan Was Real

Before the vine-swinging gets underway in the latest film version of Edgar Rice Burrough’s story about a white child brought up by apes, we might remember that for years before the 1912 debut of Tarzan of the Apes in the All-Story Magazine, Americans and Europeans had been hearing stories of white men going native in Africa, not just in adventure fiction, but in explorers’ reports, newspaper accounts, and scientific journals. It wasn’t just orphaned aristocrats that were going missing, but entire white communities. While exploring East Africa in 1876, five years after his famous meeting with David Livingstone, Henry Morton Stanley encountered some Africans whose light complexion and European features aroused his curiosity “to the highest pitch.” They came from the slopes of Gambaragara, a snow-capped mountain west of Lake Victoria. That such a towering range existed in the heart of equatorial Africa was astonishing enough. “But what gives it peculiar interest,” Stanley wrote, “is that on its cold and lonely top dwell a people of an entirely distinct race, being white, like Europeans.” Stanley’s claim caused a sensation. In the months ahead, it was reported all over the world.

Other explorers brought home similar stories. In 1904, University of Chicago anthropologist Frederick Starr brought back nine hundred feet of motion picture film to document the Ainu of Hokkaido as the “aboriginal Caucasian inhabitants of Japan.” The same year that Tarzan came to press in 1912, Canadian anthropologist Vilhjalmur Stefansson returned from the Arctic reporting the discovery of “Blond Eskimos” who behaved like the Inuit but looked “like sunburned, but naturally fair Scandinavians.” A few years later, the American entrepreneur Richard Marsh returned to Washington from an expedition to Panama where he reported the discovery of “White Indians.”

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

Scientists sifted through the reports of these anomalous encounters— flaxen-haired Indians, blue-eyed Inuit, round-eyed Japanese— in hopes of connecting the dots of racial geography to form a picture of the white racial past. Out of these efforts came a theory, the Hamitic Hypothesis –named after Ham, the cursed son of Noah from Genesis 9– positing that the world’s light-complexioned indigenes were the result of an ancient Caucasian invasion from Central Asia. As it turns out, none of these white tribes turned out to be white, at least in the racial sense of the term intended by explorers. The “White Indians” of Panama were albinos, the Ainu of Japan and the “Blond Eskimos” of Victoria Island descended from ethnic groups distinct from the general population. Henry Morton Stanley’s “white race of Gambaragara” remains a mystery, but may have been a population of light-skinned East Africans who lived in the rainforests of the Ruwenzori Mountains.

Yet the legacy of these discoveries had profound consequences for the world, especially for the people of Africa. In the existence of white tribes, Europeans found justification for their conquest and colonization of the world. If the European race had its own long history on the continent, it followed that the Europeans who followed Stanley into Africa were not settling, but re-settling, lands that had been conquered by fair-skinned invaders centuries before. As such, the white-complexioned Gambaragarans provided supporting evidence to an argument that redefined Africa’s past, and more importantly set its course for the century ahead.

None of this should be laid at the door of Edgar Rice Burroughs. He was a pencil sharpener wholesaler when he wrote Tarzan of the Apes. His novel reflected, rather than directed, the events of his age. Yet beneath its fantastic plot lay a thought experiment. How would an Englishman without his tweeds, gun, and Oxford degree size up alongside the African? How would a viscount or earl perform once the veneer of polite society had been stripped away? The answer: pretty awesome. This is the racial fantasy that, despite its many revisions and movie incarnations, clings Jane-like to Tarzan as he swings through the twenty-first century.

For more on this subject, read (shameless plug) my book:

The Lost White Tribe: Explorers, Scientists, and the Theory that Changed a Continent

Interview on New Books Network

Two years ago, I found the New Books Network on I Tunes, and I’ve been hooked ever since. Specialists talk to authors about their new books in interviews that last an hour or more. These lo-fi podcasts sound a bit warbly, but the results are intellectually high-audio, offering broad-ranged and fine-grained profiles of books that outmatch the offerings of the New York Times Book Review, the Wall Street Journal, or specialist journals. It is a book geek’s guide to paradise, and it has become one of my favorite tools for vetting books that I can enjoy in podcast form or want to read in full.

Given my love of the network, it was a real pleasure to talk to University of British Columbia historian and NBN interviewer Carla Nappi about my own book The Lost White Tribe: Explorers, Scientists, and the Theory that Changed a Continent (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016). Nappi is the Terry Gross of the NBN world, a worldly & whip-smart scholar who carefully reads every book she discusses in her author interviews (now numbering over 300). That these books cover the range between Biomedical Computing and the Tokyo Zoo demonstrates Nappi’s exceptional range across the fields of East Asian Studies and Science, Technology, and Society. Thanks Carla & NBN. The interview is available in I Tunes and on the NBN website.

Exploration: A Very Short Introduction (book review)

Exploration: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015)

Oxford’s Very Short Introduction series spans 500 volumes, taking up subjects from Beauty to Relativity to Wittgenstein. As we lose ourselves in ever expanding information networks, the brightly coloured paperbacks have become the researcher’s Lonely Planet, a pocket guide to topics that require some navigation. While the series covers some of the same ground as other reference sources insofar as they chronicle events and basic principles, their real value lies in the perspective of their specialist authors who, in addition to detailing facts, take on the central issues and controversies of their subjects.

This is hard to do in 35,000 words. It is especially hard to do with exploration which spans history and prehistory and crosses disciplinary boundaries from history, geography and anthropology to literary theory. From what perspective can all of these topics and approaches be surveyed in 130 pages? Is it possible to give appropriate scope to the subject as a whole and still say something meaningful about the explorer, the subaltern, the contact zone or the encounter?

In Stewart Weaver’s hands, yes. Written with a deft touch, his account of exploration gives scope while still finding room for subjects that require special detail and analysis. Beginning with a reflection on the idea of exploration – a term that after all this time is still difficult to pin down – Weaver establishes a central theme of the book: exploration is much more than a history of travels and conquests. “Far from expressing an eccentric wandering urge on the part of some rugged visionary, [exploration] is the outward projection of cultural imperatives shaped and elaborated back home” (7).

Chapters follow on travel in human prehistory, ancient exploration, the Age of Discovery, the Enlightenment, the Imperial Age and extreme exploration in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. While histories of exploration commonly focus on European and North American activities, Weaver provides numerous accounts of non-Western explorers: from Polynesian navigators venturing into the Eastern Pacific and the peripatetic adventures of Ibn Battuta to the magisterial voyages of Zheng He into the Indian Ocean. Important subjects receive concentrated focus. The Columbian voyages of the late 1400s, which transformed Atlantic peoples on three continents, is given considerable attention. The voyages of James Cook in the Pacific, the long five-year trek of Alexander von Humboldt through the Americas, and the western expedition of Lewis and Clark are also given room.

All of this makes A Very Short Introduction to Exploration a very useful text: accessible for a quick overview of events but also deep enough for a close examination of important episodes. For this reason, it is an appropriate work for lay readers, university students, as well as researchers seeking to contextualise their projects. Researchers will also appreciate Weaver’s nuanced knowledge of exploration scholarship. In general, Very Short Introductions avoid footnotes and restrict references to a short section in the back matter. Still, Weaver manages to infuse his chapters with the flavour of contemporary debates about exploration.

One example of this is his treatment of Alexander von Humboldt. Of the famous Prussian explorer – known in the world of nineteenth-century science not merely for his travels in South America, but for his virtuosity in representing nature graphically and holistically –Weaver provides a portrait that goes beyond a simple play-by-play of his travels. A hero in the Victorian Age, Humboldt (the subject of a special issue of Studies in Travel Writing Studies in Travel Writing, 2016 Vol. 20, No. 1, 116–117 edited by Peter Hulme in 2011) became a contested figure in the 1980s and 1990s during the postcolonial turn for being an agent of empire, doing the bidding of the Spanish crown in its attempts to maintain control over its restive colonies. Given the restrictions of the format, Weaver cannot name names, but he is clearly referring to the work of Mary Louise Pratt and others who put forward this critique of the explorer in the early 1990s. Yet he does not stop there, describing a new interpretation by Aaron Sachs and Laura Dassow Walls that recovers Humboldt from being a mere agent of empire. In their works, he emerges as a pioneer of civil rights and human ecology.

This is only one example. David Northrup’s theory of “Globalization and the Great Convergence” informs Weaver’s discussion of prehistoric exploration, Felipe Fernández-Armesto’s views are put forward in his treatment of Columbus, and even the findings of molecular biologist R. P. Ebstein – whose work on the dopamine D4 receptor raised the idea of an “adventure gene” in the late 1990s – is described in analysing the motives behind exploration. One senses, in these new biological approaches, that we have returned full circle to the late nineteenth century when “Arctic fever”, “mountain madness” and other metaphorical maladies were diagnosed as behaviours innate to our species: a will to explore.

Ultimately, while Weaver allows room for the effects of biological imperatives on exploration at both the level of the species and the individual, his emphasis is clearly on culture as the engine of expeditionary zeal, the driver of imperial encounters as well as quests to conquer “the extreme”. Still, the vast reach of exploration across the ages, encompassing so many human actors, activities and motivations resists easy generalizations. Weaver is too nuanced a thinker and too careful a historian to make epic pronouncements, but in this pocket-sized grand tour of human travel across the centuries, he offers a small one: “Exploration is always surprising; it defeats expectations,

challenges certainties, even opens eyes from time to time” (9).

Originally published as “Exploration: a very short introduction,” Studies in Travel Writing, 20:1, 116-117, DOI: 10.1080/13645145.2015.1136093

Book Talk at the Explorer’s Club on 3 May

I’ll be giving a talk at the Explorers’ Club about my new book in Boston on 3 May. Social reception at 7pm. Lecture at 8pm. More info here.