Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationArchive for Popular Culture

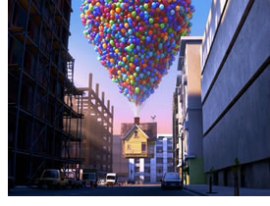

Film Review: Up

Carl Fredricksen under attack by explorer Charles Muntz

Since the release of the Incredibles in 2004, Pixar has proven that it can run with grown-ups as well as the kindergarten crowd. Kid movies, after all, will always have multiple audiences. The trick is to produce stories that cohere as well as engage these different movie-goers. The Batman and Bugs Bunny of my youth did this by packing episodes with jokes, allusions, and celebrity guest stars geared to my parents. No matter, the shows had enough fights, cliff-falls, and shotgun-blasts to keep me watching.

Pixar’s strategy, however, has been more ambitious: to produce films that pull in adults by compelling stories rather than sophisticated jokes.

The Incredibles (2004), for example, broke with a tradition of scripting superhero movies as bildungsroman, coming-of-age stories for teens with mutant powers. Instead it told the story of superheroes as they are getting soft, wrestling with the demands of family life, middle age, and lost ambitions. While there are plenty of explosions and chase sequences, the real action of The Incredibles is in the livingroom, when Bob Parr (Mr Incredible) spars with his wife Helen (Elastigirl) about life’s priorities.

The Incredibles (2004)

Up boasts no superheroes or spandex, but it follows The Incredibles‘ lead by creating a protagonist, Carl Fredricksen (Ed Asner), widower and would-be adventurer, who has seen brighter days. When we meet Carl, he is grieving the loss of his wife Ellie (Ellie Docter). After a court pressures him to sell his house and enter a retirement community, he uses his balloon expertise to turn his Victorian house into a helium dirigible, sailing aloft and out of reach of contractors and nursing home attendants.

He decides to steer his craft south, towards the mythic South American land of Paradise Falls, a place he dreamed of visiting with Ellie since they formed an adventure club as kids. Only after lifting off does Carl realize that he has a passenger, Russell (Jordan Nagai), a Wilderness Explorer trying to earn an “Assisting the Elderly” merit badge.

Russell

What inspires me to write about Up here? Because the film is about exploration in the many senses of the word. From its opening shot, Up creates a backstory for Paradise Falls, a lost world which was explored by wealthy adventurer Charles Muntz (Christopher Plumber) in his dirigible, The Spirit of Adventure. Muntz returns claiming discovery of a large flightless bird, meeting with ridicule. With no proof of his discovery, he is stripped of his membership in the National Explorer’s Club, and leaves on The Spirit of Adventure (with a large pack of dogs) vowing to return once he has proven his claim to the world.

Charles Muntz, explorer of Paradise Falls

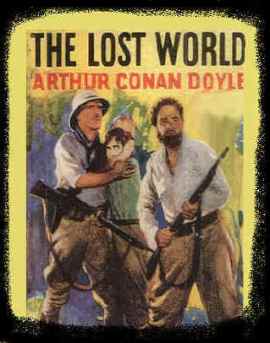

Muntz’s exploration of South America borrows much from Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1912 book, The Lost World, which also tells the story of a South American expedition (led by Dr. Challenger) who is ridiculed for claiming the discovery of living dinosaurs.

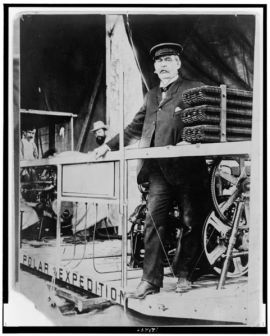

Yet as a wealthy explorer with a keen sense of technology, Muntz also resembles Howard Hughes, piloting the H-4 Hercules (Spruce Goose) in 1947, and Walter Wellman, who steered the dirigible America toward the North Pole in 1906. He also reminds me of Frederick Cook, whose claims of discovering the North Pole in 1909 eventually brought about public ridicule and expulsion from the Explorers Club the following year. (As for Muntz’s dogs, trained to perform human tasks and provided the power of speech, I couldn’t help but think of The Island of Dr. Moreau by H. G. Wells).

Walter Wellman aboard America

As for the giant flightless bird of Paradise Falls (named “Kevin” by Russell), it could be an allusion to Doyle’s dinosaur, but it also made me of the most famous description of a South American flightless bird, Charles Darwin’s discovery of the Rhea in 1833, a find that had serious implications for his theory of evolution.

Kevin, flightless bird of Paradise Falls

Rhea Darwinii

More compelling than these historical and literary allusions, however, are the deeper questions Up raises about the idea of exploration. As children, Carl and Ellie bonded over the idea of exploring Paradise Falls, a dream that was never realized during Ellie’s lifetime. It fuels Carl’s quest to reach the mythic locale after her death. Yet once he reaches the Falls, Carl opens up Ellie’s childhood “My Adventures” scrapbook to find that the pages after “Paradise Falls” are not empty, but filled with pictures of Carl and Ellie through the happy years of their marriage. Adventure – Ellie knows – is where you find it, and discovery, as William Goetzmann points out in Exploration and Empire, is almost always a question of re-discovery, finding new things in places already traveled.

Ellie and Carl

Most of all, Carl’s insight into the idea of adventure reminded me of Philip Carey, protagonist of Somerset Maughm’s novel Of Human Bondage (1915). Although Carey nurtured a lifelong dream to travel, he eventually decides to shelve this plan when he falls in love, seeing a different path to discovery:

What did he care for Spain and its cities, Cordova, Toledo, Leon; what to him were the pagodas of Burmah and the lagoons of the South Sea Islands?…He had lived always in the future, and the present always, always had slipped through his fingers. His ideals? He thought of his desire to make a design, intricate and beautiful, out of the myriad, meaningless facts of life: had he not seen also that the simplest pattern, that in which a man was born, worked, married, had children, and died, was likewise the most perfect?

Charles Muntz is the most traveled character of Up. He is also the least enlightened by his travels, scarcely touched by his experiences of Paradise Falls except for his obsessive quest with finding the flightless bird. Ellie, by contrast, never leaves the suburbs and the zoo where she works. But she understands that exploration is a state of mind as much as a plan of action, an experience that does not require talking dogs or dirigibles.

Wild Thing

Woodwose (detail), Albrecht Durer, 1499

Whether going up mountains, down rivers, over canyons, or across the pack-ice, adventurists often express a malaise with “civilized life” back home. In the wild, the drudgeries of the mall-shopping, lawn-mowing, 401K-filing world fall away, and with them, the barriers to authentic experience. Says Mt Everest climber Stephen Venables:

Although you don’t deliberately seek an epic, you know that one day something like that might happen. When it did happen on Everest, it was harder and more prolonged and draining than anything I had ever done, but also more exhilarating than anything I had ever done. It was like a watershed. It was something I was probably never going to repeat again. [quoted in Maria Coffey, Where the Mountain Cast Its Shadow, 137]

Why does civilization make some people feel so queasy that they’d travel to the most dangerous places on earth to find relief? A common answer is that human beings are not well-adapted to the world they inhabit, that some deeply buried instinct drives us to leave our suburban ghettos and take up high-altitude mountain climbing. A related argument holds that humans are innately curious, so curious that they are impelled, like cats near washing machines, to explore at any cost.

I don’t like these explanations. No one doubts that human beings have inherited behaviors, all animals do, but humans have proven remarkably plastic as a species. Speech patterns, fashion, diet, and language all show how impressionable we are to environment, experience, and culture.

Perhaps this reveals my bias too: as a cultural historian, I tend to think of explanations that are cultural rather than biological. In this case, I am inclined to believe that explorers and adventurers find catharsis in the wild because, well, they have learned to think of such places as cathartic.

Historians such as T. J. Jackson Lears and Gail Bederman have built a strong case for this argument. Looking at a wide array of evidence from the 19th and early 20th centuries, they link the urge to return to nature with cultural events. In particular, “going native,” Primitivism, and the Arts and Crafts movement all gain popularity just as Western societies transition from agricultural to industrial economies. For Lears and Bederman, the “call of the wild” has less to do with the feral impulses of the human psyche, and more to do with the disorienting world of the industrial city.

Tarzan of the Apes (Cover), Edgar Rice Burroughs, 1912

Yet, I will admit, the “call-of-the-wild” impulse cannot be entirely explained by culture either. If we travel back in time before industrialization, we can still find a certain malaise with civilization.

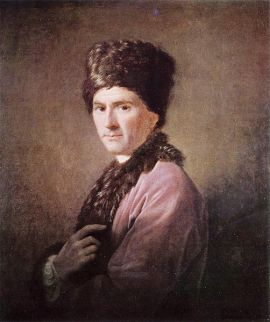

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Allan Ramsay, 1766

Living in 18th century Paris, Jean-Jacques Rousseau railed against the vanities and corruptions of civilized life. He found role models in the islands of the South Pacific where native peoples lived – so he thought – more virtuous lives closer to nature.

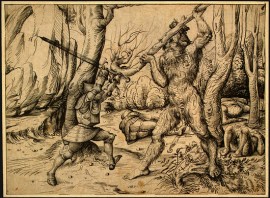

The Fight in the Forest, Hans Burgkmair, 1500 CE

We can go back even further. For Medieval Europeans the “Wildman” was a common, if legendary, figure in art and literature. Often, wildmen represented civilized men who, in the throes of madness, grief, or unrequited love, cast off everything and entered a state of nature. They reverted to savagery, acted violently, and lost their powers of speech and reason. Yet when these wildmen, by chance, were returned to the civilized world, they often emerged better for the experience: stronger of spirit and purer of heart. Such was the case with Merlin of the King Arthur legends.

Even the ancient Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, which dates to at least 2000 BCE, features the feral wild-child Enkidu, a boy raised by beasts and ignorant of all of civilization’s pleasures until seduced by the temple prostitute Shamhat. No industrial cities here.

What to make of all this? Perhaps there is something of the “call-of-the-wild” that strikes deep, beneath the reaches of culture (is there such a place?). From what we know, it appears that human beings spent most of their 125,000 year history in motion, as nomadic, itinerant tribes. Only in the last 10,000 years or so have we put down roots, developing agriculture and the foundations of complex, specialized societies. Is this restlessness a a biological shadow of our long journey as hunter-gathers? A vestigial organ of the civilized psyche? I never used to think so but I wonder.

The Myth of the Popular Audience

Every year I attend two or three academic conferences, mostly to keep up with friends and sneak-preview new research. Usually the best material (about friends and research) emerges from conversations in bars and hotel lobbies rather than in the faux-walled conference rooms where panelists deliver their papers. I know many colleagues who avoid the panels all together, afraid of being caught in a boring session from which they cannot (politely) escape.

Why is this? Most of the historians I know are diligent and innovative teachers, people who care about communicating with their students, who allow a great deal of back and forth in the classroom. But something strange happens when they go to conferences. Suddenly the vibrant professor is transformed into the paper-reading scholastic, delivering his/her monotone lecture as if s/he were a medieval instructor in front of young, suffering novitiates.

It makes me think that we overstate the divide between scholarly and popular audiences. Is the public all that different from the Academy in what it wants from a lecture? I want to hear talks that are well developed and delivered, talks that do not assume too much about my knowledge of the subject, talks that keep to their allotted time, talks that make a point. Isn’t this what everyone wants?

If academic and popular audiences are more similar than we think, perhaps we should also reconsider our assumptions about lecture content. Academics often make distinctions about subjects appropriate for their peers and those appropriate for everyone else. Sometimes these distinctions are warranted, particularly for talks that require a lot of theoretical knowledge at the outset. But theory is not the Iron Curtain separating scholars from public that we make it out to be. Often a quick tutorial in theory can be developed within the talk if the point is important enough.

My experience giving public lectures over the past two months have convinced me of this. While I have had to limit some of the details of my work, the structure and arguments of my talks has closely followed my scholarly writings. My talks begin with anecdote, some context, an argument, and then pieces of evidence to defend the argument. They end with a short conclusion about “why all of this matters.” Overall, I’ve gotten a good response.

What would happen if academics wrote papers for their peers as if they were addressing the general public?

Maybe things are already getting better. In the last conference I attended — the History of Science Society Annual Meeting in Pittsburgh — the papers were terrific. I chaired a panel that was focused and snappy. Everyone used images to illustrate their points. The panels I attended held their own against the meetings of peers in bars and lobbies…except, perhaps, for the drinks.

New Arctic Exhibition

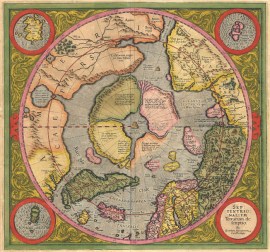

Septentrionalium Terrarum Descriptio, Gerard Mercator, 1611. A polar projection showing islands and open water at the North Pole.

Apologies for the spare postings over the last two weeks. I’ve been doing a lot of out of town projects. Last week I was down in DC where Story House Productions is putting together a documentary on the Cook-Peary North Pole Controversy of 1909. They interviewed me in the historical newspaper room of the Newseum (just off the National Mall). Museums are strange places anyway, but after dark they become positively surreal.

News History Gallery, Newseum, Washington DC.

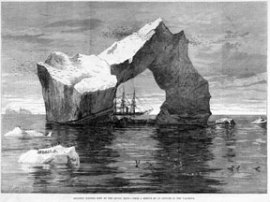

I was also up in Maine working out the kinks of an exhibition I am curating at the Portland Museum of Art called “The Coldest Crucible: Arctic Exploration in American Culture.” The show examines many of the same themes as my book (no surprise). But where my book was limited to 18 black-and-white prints, the exhibition delivers a much broader range of paintings, photos, and illustrations. The point is to show how the Arctic of these images represents a hybrid-world: a vision of polar regions, colored by the aesthetics and preoccupations of the Americans who traveled there.

Gigantic Iceberg Seen By the Arctic Ships, From a Sketch by an Officer of the Valorous, Illustrated London News, 1875

You can see some of the images of the show here.

I gave an interview about the exhibition on Channel 6 while I was there.

The show opens this Saturday and runs through 21 June.

Asia on Top

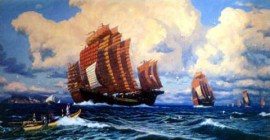

Zheng He's fleet sailing the Western (Indian) Ocean, 1405-1433. 20th century painting, artist unknown.

Exploration seems an inclusive concept, a big-tent activity that admits anyone with a geographical goal and a good pair of shoes. But like most terms, exploration has hidden meanings and rules, ones that restrict certain places, people, and activities.

For example, Americans have made a national mythology out of exploration, creating a genealogy of pioneers and explorers that extends from Lewis and Clark in 1804 to Neil Armstrong in 1969. Were extraterrestrials listening in to the speeches of the 2008 Democratic National Convention, they would be forgiven for thinking that Americans single-handedly discovered the world. (For more on exploration talk at the DNC, read this)

Yet even the most blinkered American manifest-destinorians would have to extend the “spirit of exploration” to Europeans. Otherwise they would have to exclude the Renaissance all-stars of exploration, Christopher Columbus, Vasco da Gama, and Ferdinand Magellan, from their ranks.

Protestant Americans wrestled with exactly this issue in the 19th century, ultimately deciding to embrace southern European explorers as a part of their own cultural heritage. In their favor, Columbus and his successors were white Christians, even if they suffered from being papists, speaking Spanish and Italian, and drinking wine on Sundays.

Columbian Exposition Commemorative Half Dollar, 1892

But this is about as inclusive as Americans have been willing to get. Expeditionary activities of African and Asian nations are duly reported of course. Western press agencies keep us apprised of the South African National Antartic Programme (SANAP) and the Chinese Shenzhou Space Program. But one detects in western press coverage a view that these accomplishments are adaptations to a Western philosophy of discovery, a mimetic activity rather than something which expresses core features of Asian or African culture.

Put differently, exploration has become the symbolic equivalent of baseball, an activity played all over the world, but still seen in the U.S. — now and forever more — as an archetypally American game (debts to cricket aside).

Were we to sit down with early European navigators in the 15th century, I think they would be astonished by all of this Euro-American strutting and preening. After all, exploration took off in Europe because Europeans felt they were being pushed off the stage of world events.

Despite the pageantry of statues and paintings, the European Age of Discovery was less about curiosity than fear and admiration, an appreciation for non-European powers, particularly in Asia, that held the keys to European collapse or prosperity.

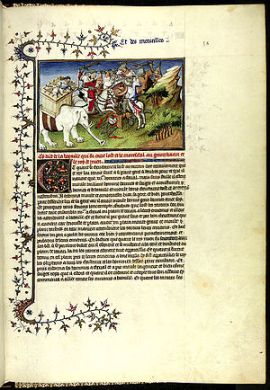

For medieval Europeans, the Orient was the center of the world. It was the font of Judeo-Christian religious history, the site of the Holy Land. It was the center of global commerce and trade, particularly luxury items. While Frankish farmers ate mutton and plowed their fields in scratchy woolens, Marco Polo enchanted readers with stories of silks, teas, and concubines from Cathay.

Travels of Marco Polo, manuscript page, 1298

Meanwhile Crusaders brought back cinnamon and clove from the Spice Islands and cottons from India. As for geopolitical power, any Pole, Serb, or Castilian from the late Medieval period would have stories to tell about the powerful pagans of the East. One forgets that before the centuries of European hegemony, European border kingdoms were continually reacting to events from empires East: Mongols, Persians, and Ottomans.

Evidence for this comes from many sources. The importance of the East is pounded into the English language of geography. For example, the word for Eastern lands “Orient” (Chaucer, 1375 CE) soon begot words of directionality such as “orientality” (Browne, 1647 CE) and “to orient” (Chambers, 1728 CE).

Moreover, European cartography expressed a Eastern-centric vision of the world. European T-O maps produced in late medieval Europe usually faced East and centered on Jerusalem. It was common for such maps to also overlay important religious symbols such as the body of Christ or the sons of Noah on the world’s continents.

T-O map from the Etymologiae of Isidorus, 1472. Asia is on top, Europe is bottom left, Africa is bottom right. The names of Noah's sons are placed under each continent.

Mappa Mundi showing Noah's ark and three sons on three continents in La Fleur des Histoires, Valenciennes, 1459-63

European conquests in Asia and America in the early 16th century did much to boost European self confidence. (See for example, Abraham Ortelius’s frontispiece for his 1580 Atlas in my post on cannibalism)

There is much more to be said about Asia in the history of exploration, particularly 19th century conceptions of the East and Edward Said’s influential work Orientalism. All of that will have to wait for another post though. For now, here are a few links on history, travel, and exploration in Asia:

The Silkroad Foundation “The Bridge Between Eastern and Western Cultures”

The Athena Review Journal of Archeology, History, and Exploration

Astene Association for the Study of Travel in Egypt and the Near East