Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationArchive for Popular Culture

First, Fastest, Youngest

Firsts have always been important in exploration. This seems rather straightforward, even tautological, to say since being first is woven into the definition of exploration. After all, traveling to unknown places is doing something that hasn’t been done before (or at least hasn’t been reported before). And this is how the history of exploration often appears to us in textbooks and timelines: as lists of expeditionary firsts from Erik the Red to Neil Armstrong.

In truth, though, firsts are fuzzy.

Some fuzziness comes from ignorance, our inability to compensate for the incompleteness of the historical record. This is a perennial problem in history in general and history of exploration in particular. (I call it a problem but it’s actually what makes me happy and keeps me employed).

Was Christopher Columbus the first European to reach America in 1492? Probably not, since evidence suggests that Norse colonies existed in North America five hundred years before he arrived. Was Robert Peary the first to reach the North Pole in 1909? It’s hard to say since Frederick Cook claimed to be first in 1908 and its possible that neither man made it.

Some fuzziness comes from the different meanings we give to “discovery.” The South American leader Simon Bolivar called Alexander von Humboldt “the true discoverer of America.” Bolivar did not mean this literally since Humboldt traveled through South America in 1800, 17 years after Bolivar himself was born there, 300 years after Columbus first arrived in the Bahamas, and about 16,000 years after Paleo-Indians arrived in America, approved of what they saw, and decided to stay.

But for Bolivar, Humboldt was the first person to see South America holistically: as a complex set of species, ecosystems, and human societies, held together by faltering colonial empires. Being first in exploration, Bolivar realized, meant more than planting a flag in the ground.

At first glance, we seem to have banished fuzziness from modern exploration. For example, there is little doubt that Neil Armstrong was the first human being to set foot on the moon since the event was captured on film and audio recordings, transmitted by telemetry, and confirmed by material artifacts such as moon rocks. (Moon hoax believers, I’m sorry. I know this offends.) Were the Russians suddenly interested in challenging Armstrong’s claim to being first, they would have a tough time proving it since Armstrong could give the day and year of his arrival on the moon (20 July 1969) and even the exact hour, minute, and second when his boot touched the lunar surface (20:17:40 Universal Coordinated Time).

But this growing precision of firsts has generated its own ambiguities. We have become more diligent about recording firsts precisely because geographical milestones have become more difficult to achieve. As a result, there has been a shift from firsts of place to firsts of method. As the forlorn, never-visited regions of the globe diminish in number, first are increasingly measured by the manner of reaching perilous places rather than the places themselves.

For example, Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary were the first to ascend Mt. Everest in 1953, but Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler were the first to climb the mountain without oxygen in 1978. In 1980, Messner achieved another first, by ascending Everest without oxygen or support.

Now as “firsts of difficulty” fall, they are being replaced by “firsts of identity.” James Whittaker was the first American to summit Everest in 1963. Junko Tabei was the first woman (1975). Since then, Everest has spawned a growing brood of “identity first” summits including nationality (Brazil, Turkey, Mexico, Pakistan), disability (one-armed, blind, double-amputee) and novelty (snowboarding, married ascent, longest stay on summit).

It would be easy to dismiss this quest for firsts as a shallow one, a vainglorious way to achieve posterity through splitting hairs rather than new achievements. But I don’t think this is entirely fair. While climbing Everest or kayaking the Northwest Passage may have little in common with geographical firsts in exploration 200 years ago, this is not to say that identity firsts are meaningless acts. They may not contribute to an understanding of the globe, but they have become benchmarks of personal accomplishment, physical achievements — much like running a marathon — that have personal and symbolic value.

Still, I am disturbed by the rising number of “youngest” firsts. Temba Tsheri was 15 when he summited Everest on 22 May 2001. Jessica Watson was 16 last year when she left Sydney Harbor to attempt a 230 day solo circumnavigation of the globe. (She is currently 60 miles off Cape Horn). Whatever risks follow adventurers who seek to be the oldest, fastest, or the sickest to accomplish X, they are, at least, adults making decisions.

But children are different. We try to restrict activities that have a high risk of injury for minors. In the U.S. for example, it is common to delay teaching kids how to throw a curve ball in baseball until they are 14 for fear of injuring ligaments in the arm. Similar concerns extend to American football and other contact sports.

So why do we continue to celebrate and popularize the pursuit of dangerous firsts by minors? What is beneficial in seeing if 16-year-olds can endure the hypoxia of Everest or the isolation of 230 days at sea. Temba Tsheri, current holder of youngest climber on Everest, lost five fingers to frostbite.

We must remember that to praise “the youngest” within this new culture of firsts, we only set the bar higher (or younger as it were) for the record to be broken again. In California, Jordan Romero is already training for his ascent of Everest in hopes to break Tsheri’s age record. He is thirteen.

Film Review: Avatar

As I went to see Avatar last week, I felt resigned. It had all of the predictors of a bad movie.

First, it cost half a billion dollars to make. This may seem promising. What film wouldn’t benefit from vast sums to improve cast, scripts, and special effects? Yet big budgets are usually the death of good films because studios become obsessed with recovering their investments. The question of “how do we make a good film” becomes eclipsed by “how do we make a film that brings in 500 million dollars of audience?” The recipe for this is well known: find big name actors, put them in a romance story which doubles as an action film, and sprinkle liberally with special effects. Toy merchandising helps too.

Second, Avatar was developed as a 3-D computer graphics film, only occasionally including scenes with human actors. While CGI has revolutionized film-making, it has often been used indiscriminately, creating scenes that are ill-conceived, implausible, or – with hundreds of moving points of animation – impossible to watch. George Lucas is the poster-child for CGI abuse. The coherence and narrative tension of the original Star Wars series was no where to be found in the prequel episodes of the last decade, as the demands of the blue-screen eclipsed plot, drama, and character development.

Third, Avatar follows two of the most cliched genres in films: it is coming-of-age movie, a bildungsroman in space, and a “going native” story where the lead, Jake Sully (Sam Worthington), a paraplegic marine, finds meaning in life by becoming a member of “primitive” tribe, the Na’vi on the planet of Pandora. This feat is made possible by the creation of a Na’vi avatar that Sully inhabits for most of the film. (To see how easily Avatar maps on to other ‘going native’ films, see these mashups here and here of Avatar & Disney’s Pocahontas)

So I was surprised that I really like this movie. The millions of dollars used in production and marketing have not corrupted the soul of Avatar. Credit for this goes to director, James Cameron, who has proven capable of directing massively expensive, CGI intensive films (Terminator, Aliens, and Titanic) without surrendering plot and coherence.

As for the CGI effects, they are stunning to behold. The planet of Pandora is rendered with brilliant color and movement, texture and imagination. The ten-foot tall Na’vi – who in the real universe would already have been recruited for the NBA, move with all of the grace of real humans, or rather, humanoids. After a few minutes, I forgot I was watching CGI, or more accurately, I forgot about the distinction between CGI and “real life.” This is a clever effect since the viewer is, in a sense, recapitulating Sully’s experience with his avatar.

Most importantly, the story of Jake Sully’s assimilation into the world of the Na’vi, while predictable, is not mawkish. It isn’t hard to believe that a man who has lost the use of his legs, spent six years in space, and no longer functions within the world of the Marines, would find running and flying through wilds of Pandora exhilarating.

Indeed, it is the idea of the avatar that keeps this ‘going native’ story interesting. Other films in this genre, from Apocalypse Now to Dances With Wolves, follow men as they cut themselves off from the world left behind. By contrast, Avatar follows Sully as he moves back and forth between worlds: his avatar existence with the Na’vi and his human existence in base camp. How does one go native if there is constant access to the world one is leaving? The moral conflict which results provides Avatar with much of its narrative tension.

Finally, Avatar proves three-dimensional in another sense, by taking this theme of remote connection beyond the story of Sully and the Na’vi. The Marines on Pandora have found their own avatars of sorts, in the weaponized “Amplified Mobility Platform” or AMP (which bears more than a passing resemblance to the cargo loader operated by Sigourney Weaver in Aliens).

The Na’vi, on the other hand, are able to link, through neuro-chemical connections to other beings on Pandora. Indeed, the planet itself operates as an organic neural network. Avatars, in other words, have many incarnations and, in their most developed states, begin to emulate a kind of Gaia or world-soul. At what point does neural connectivity cross the line into spirituality? While Avatar sometimes crosses the line into a preachy environmentalism, the bigger questions that it raises make it worth the ride.

Interview with Felix Driver

A Malay native from Batavia at Coepang, portrait of Mohammed Jen Jamain by Thomas Baines. Courtesy of the Royal Geographical Society

The history of exploration does not have its own departments in universities. It does not really exist as a historical sub-discipline either, at least in the way that formalized fields such as labor history, women’s history and political history do. Instead, the history of exploration is a disciplinary interloper, a subject taken up by many fields such as literary studies, anthropology, geography, and the history of science. Each brings its own unique perspective and methods. Each has its own preoccupations and biases.

All of which makes the work of Felix Driver, professor of human geography at Royal Holloway, University of London, especially important. While Driver has covered many of the meat-and-potatoes subjects in exploration: navigation, shipwrecks, and biographical subjects such as Henry Morton Stanley and David Livingstone, he has framed them in the broadest context: through the visual arts, postmodern theory, social history, and historical geography.

He is the author of many books and articles including Geography Militant: Cultures of Exploration and Empire. He is also the co-editor of Tropical Visions in an Age of Empire which came out with University of Chicago Press in 2005.

At the same time, Driver has worked to bring these subjects to the attention of the public, supervising the new Royal Geographical Society exhibition, Hidden Histories of Exploration. The exhibition, which opened on October 15, “offers a new perspective on the Society’s Collections, highlighting the role of local inhabitants and intermediaries in the history of exploration.”

Driver took some time to speak with me about the exhibition and his work on exploration.

Welcome Felix Driver.

What inspired the Hidden Histories exhibition?

A conviction that the history of exploration was about a wider, collective experience of work and imagination rather than simply a story of lone individuals fighting against the odds. The idea of ‘hidden histories’ has an innate appeal – it suggests stories that have not been heard, which have been hidden from history, waiting to be uncovered. It has already provided the RGS with a model for a series of exhibitions linking aspects of their Collections with communities in London. The Society’s strong commitment to public engagement in recent years provided an opportunity for a more research-oriented exhibition which asked a simple question: can we think about exploration differently, using these same Collections which have inspired such great stories about heroic individuals? This was a kind of experiment, in which the Collections themselves were our field site: together with Lowri Jones, a researcher on the project, we set out to explore its contours, trying to make these other histories more visible.

Hidden Histories uses RGS collections to look at “role of local peoples and intermediaries in the history of global exploration.” Those of us who study exploration get excited by this, but how do you pitch it to the general public? How do you engage the exploration buff interested only in Peary, Stanley, or Columbus?

That’s a good question. The exploration publishing industry has returned over and over to the same stories. The lives of great explorers continue to sell well, and that is one aspect of the continuing vitality of what I call our culture of exploration. Still, recent developments in the field and in popular science publishing have encouraged authors and readers to shift the focus somewhat, turning the spotlight on lesser known individuals whose experiences have been overshadowed. Consider for example the success of some terrific popular works on the theme of exploration and travel such as Robert Whitaker’s The Mapmaker’s Wife, or Matthew Kneale’s novel English Passengers, which are all about large and complex issues of language, translation, misunderstanding and exchange. That gives you a bit of hope that actually readers are looking for something new, so long as there is a good story there! Of course it is not easy – so much simpler to tread the path of our predecessors. Sometimes it requires an exploring spirit to venture further from the beaten track….

What first drew you to the history of exploration? Is there particular question or theme that guides your research? How have your interests changed over time?

What drew me first to the history of exploration was a growing realization that the subject was more important to my own academic field – geography – than my teachers in the 1970s were prepared to admit. I was interested in the worldly role and impact of geographical knowledge, socially, economically and politically. When I was at school and college, ‘relevance’ was in the air and geographers were turning their attention to questions of policy and politics. My point was that geographical knowledge has been and continued to be hugely significant in the world beyond the academic, from travel writing to military mapping, and exploration provided one way into this. There were other ways into this worldly presence, of course, and the work of my PhD supervisor Derek Gregory has had a lasting influence.

Much of my own writing has focused strongly on the long nineteenth century, partly because this was a period in which I immersed myself for my PhD and first teaching (my first post was a joint appointment in history and geography). However, I was drawn to the work of social historians – at first EP Thompson’s Making of the English Working Class, later work influenced by new models of cultural history. Partly because of my appointment on the borders of two disciplines, I found myself increasingly attracted to fields – such as Victorian studies or the history of science – that were in a sense already interdisciplinary. In both these cases, an interest in space and location has had a strong impact on the best writing in the field. Historians like Jim Secord and Dorinda Outram, as well as geographers such as David N. Livingstone and Charles Withers, taught me a lot about the ways in which ideas about exploration circulate, and why it is important to think of knowledge in practical as well as intellectual terms.

My interest in the visual culture of exploration and travel reflects the strong focus on the visual has shaped the work of geographers in this area, pre-eminently Stephen Daniels and Denis Cosgrove. My interests developed through work with James Ryan, whose book on the photographic collections of the RGS remains a seminal work. Later I worked with Luciana Martins on a project on British images of the tropical world in which we were particularly concerned with the observational skills of ordinary seamen and humble collectors rather than the grand theorists of nature. In retrospect, this project paved the way for some of the themes in the hidden histories of exploration exhibition. But this exhibition also represents a departure for me as the focus is squarely on the work of non-Europeans. There is an interesting discussion to be had here about whether turning figures like Nain Singh or Jacob Wainwright into ‘heroes’, just like Stanley or Livingstone, is the way to go. Perhaps we can’t think of exploration without heroes, and it’s a matter of re-thinking what we mean by heroism. Or perhaps we historians need to do more than ruminate on the vices and virtues of particular explorers, by considering the networks and institutions which made their voyages possible and gave them a wider significance.

In Geography Militant, you warned that scholars were focusing on exploration too much as an “imperial will-to-power” [8] ignoring the unique and contingent qualities of each expeditionary encounter. You developed this argument further in Tropical Visions in an Age of Empire. Do you think scholars are now moving away from an “empire-is-everywhere” world view? If so, what do you think we are moving towards?

This is not an original view. Many of the best known historians and literary critics writing on empire have made similar points: I am thinking of Peter Hulme, Catherine Hall and Nicholas Thomas. What I take from them is a deep sense of what colonialism and empire meant – not just at the level of trumpets and gunboats, but in the very making of our sense of ourselves and our place in the world, past and present. At the same time, I have wanted to highlight the fractured, diverse nature of the colonial experience and I have never been happy with lumpen versions of ‘colonial discourse’ which used to be advanced within some versions of postcolonial theory. This interest in difference is reflected in my interest in moments of controversy and crisis, points where the uncertainties and tensions come to the surface (as in controversies over the expeditions of Henry Morton Stanley). You can’t work on exploration for long without realizing the strong emotional pull of the subject on explorers and their publics; and the fact quite simply that they were always arguing, either with ‘armchair geographers’ (those much maligned stay-at-homes) or with their peers. If these arguments were frequently staged if not orchestrated by others, that is part of the point: these controversies were more than simply the product of disputatious personalities, they were built in to the fabric of the culture which produced them.

What’s your next project?

In recent years I have worked on a variety of smaller projects on collectors and collecting, involving everything from insects to textiles. What I would like to do next is a book on the visual culture of exploration, drawing on a wide variety of materials from sketch-books to film. Some of these materials are represented in the hidden histories exhibition, notably the sketchbooks of John Linton Palmer and the 1922 Everest film featured on the website. But there is much left to explore!

Thanks for speaking with me.

Your work focuses on many issues besides the history of exploration, including visual arts, the geography of cities, and questions of identity and empire.

The Remotest Place on Earth

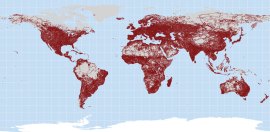

Travel times to major cities. Shipping lanes in blue. Image Credit: NewScientist

This week, NewScientist announced the remotest place on earth: 34.7°N 85.7°E, a cold, rocky spot 17,500 ft up the Tibetan Plateau. From 34.7°N 85.7°E it takes three weeks by foot to reach Lhasa or Korla.

Not that anyone has tried. No council of explorers advised NewScientist on its choice of locations. It was determined by using geographical information systems (GIS) which combined number of factors, including:

information on terrain and access to road, rail and river networks. It also consider[ed] how factors like altitude, steepness of terrain and hold-ups like border crossings slow travel.

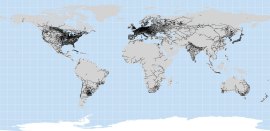

The world's roads. Image credit: NewScientist

Nineteenth century maps still occasionally showed regions of Terra Incognita. But twenty-first century maps have no blank spaces left. The NewScientist maps offer, in their measure of “most remote” a modern equivalent.

The world's railroads. Image credit: NewScientist

Finding the remotest place on earth is an interesting project. In tracing this circulation system of human movement, we see how closely it correlates to areas of wealth and industrialization. Still I wonder if human movement – specifically how long it takes to reach a major city – is the best way to measure remoteness. Today cell phones and the internet connect people in some of the world’s loneliest places. There are no roads or trains that reach the pinnacle of Everest. Yet it can be reached by cell phone, observed from base camp by telescope, viewed in three dimensions through satellite images in Google Earth.

The world's navigable rivers. Image credit: NewScientist

By contrast, there are places within the bright regions of the NewScientist map where connectivity fails. A resident of the Ninth Ward of New Orleans or Cairo’s City of the Dead are only minutes away from a web of roads, rivers, and trains. Yet how often do residents use them? In these cases, remoteness is not a matter of distance, but of culture and socio-economics. How do we measure these kinds of blank spaces on the map?

The Explorer Gene

In 1987, Dr. C. Robert Cloninger created the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire (TPQ). Despite its unique, Star-Trekian name, Cloninger’s TPQ entered a crowded field of personality tests, such as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), the Enneagram, and the Oxford Capacity Analysis (OCA).

Spock administers the TPQ to Captain Kirk

The TPQ distinguished itself in two respects.

First, it came from a trusted source within the medical establishment. Cloninger, a medical doctor and professor of psychology at Washington University in St. Louis, developed the TPQ from clinical research.

Second, Cloninger’s test made claims about the genetic origin of behavioral differences. Specifically, it argued that important aspects of personality are heritable, that our temperament grows out of genetic factors as much environmental ones.

As Cloninger sees it, the route from gene to expressed behavior follows a path laid down by neurotransmitters, particularly seritonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. The three dimensions of the TPQ (which measure harm avoidance, reward dependency, and novelty seeking) correspond to different sensitivities in these three neurotransmitters.

Cloninger’s TPQ, now somewhat modified, remains controversial within the field of psychology. Some studies confirm a link between personality assessment and neurotransmitter sensitivity while others do not. In 1996, two studies in the United States and Israel found a correlation between a high proclivity for novelty seeking and a longer sequence in the D4 dopamine receptor gene.

Scientists hypothesized that the added length of the D4Dr sequence made certain individuals particularly sensitive to changes in dopamine. High levels of dopamine — secreted in moments of pain, pleasure, or excitement — would lead to an intense high. By contrast, moderate levels of dopamine would leave the long D4Dr individual feeling depressed.

Novelty seeking, then, was not simply an acting out against one’s parents or the product of a mid-life crisis. It was long-D4Dr individuals’ attempts to self-medicate: to BASE jump, drag race, and free climb their way to their next rush of dopamine.

The discovery of the long D4Dr gene in 1996 captured popular attention. Was exploratory behavior more a matter of genes than life experience? Did Lord Byron chase maids and attack Turks because of a mutation on his 11th chromosome? Was Columbus’s discovery of America an elaborate attempt to get high?

Such genetic arguments are simplistic. Recent studies have brought the TPQ test and the D4Dr-novelty seeking link into question. Moreover, as Maria Coffey points out in her book, Explorers of the Infinite, many of the riskiest activities — such as high altitude mountain climbing – come with long periods of drudgery. If high-risk activity is the key to unlocking an individual’s neuro-chemical Valhalla, the long D4Dr adventurer would do better working as a day-trader on Wall Street or playing the $500 tables in Atlantic City.

What’s more interesting to me is idea that “exploratory behavior” is an impulse beyond our control. This is a distinctly modern idea, though one that expressed itself somewhat differently in the 19th century. At that time, polar explorers called it “Arctic fever” a metaphor that was appropriate for an era afflicted by contagious disease. I find it interesting that late 20th century audiences have placed this impulsive, cannot-be-reasoned-with desire for danger within the human genome.

One might argue that the idea of the D4Dr is rooted in modern scientific research, that it represents something real rather than the 19th century’s metaphor of “fevers.” Still this doesn’t explain why talk of the explorer gene continues today even after the scientific evidence has left it behind.

For example, the dopamine-craving would-be adventurer can still join the D4Dr Club which bills itself as “the ultimate social club for adventure seekers of all types.”

No genetic testing is necessary. If you have an elongated D4DR, you probably know it. Be proud of it! Flaunt it! Whatever your ‘thing’ is – Adventure Travel, Extreme Sports or if you just like an adrenaline rush.

Membership benefits include a newsletter, inclusion in studies about the D4Dr gene, and a discount on flak jackets.