Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationTouchdown! Mars Phoenix Lander

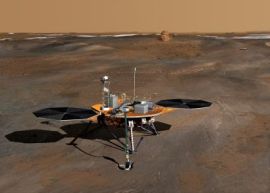

Touchdown! The Mars Phoenix Lander transmitted this image a few minutes ago. Congratulations to the University of Arizona. Go Wildcats. See yesterday’s post for more.

Mars Phoenix Mission

Tomorrow I’ll be watching two flying objects: the Phoenix Lander, a $420 million dollar spacecraft descending towards the polar plains of Mars, and Michael Fournier, a 64-year-old Frenchman who will be hurtling towards the bucolic pastures of Saskatchewan.

The Phoenix Lander comes equipped with a robotic arm camera, surface stereo imager, and thermal and evolved-gas analyzer. Fournier comes equipped with a space suit lined with wool underwear. If all goes well, both Lander and Fournier will deploy parachutes. The Mars Lander will spend its post-touchdown period testing the Martian soil to see whether water exists near the Martian poles and if it could support life. Fournier will spend his post jump moments speaking to the press and thanking his supporters. Fournier’s jump, if successful, will establish a record for highest human balloon flight and break altitude, speed, and time records for freefall. Not that this makes any difference to Fournier I guess:

“It’s not a question of the world records,” Fournier wrote via e-mail through an interpreter on Friday from his base in North Battleford, Saskatchewan. “What is important are what the results from the jump will bring to the safety of the conquest of space. However, the main question that is being asked today by all scientists is, can a man survive when crossing the sound barrier?”

Whether someone can break the sound barrier without becoming a human flank steak, is, I guess, a question that burns in the mind of Michel Fournier. But it is not “the main question that is being asked today by all scientists.” If Fournier really believes this is about science and not about personal glory, wouldn’t it be simpler (and safer) to send a crash-test dummy up instead? After all we have machines nowadays that measure pressure and temperature and others, called transmitters and receivers, that can relay this sort of information to earth. Maybe this was cutting edge technology back in the age of the V-2, but its pretty routine today. Oh, and no one dies.

The North Pole Controversy

Solving the mystery of the North Pole is like trying to solve a murder. Lacking witnesses, we rely heavily upon circumstantial evidence. We cannot trust Peary or Cook’s accounts since they had strong motives for bending the truth. We cannot trust the accounts of the men who accompanied them because none of them were capable of calculating their geographical position using sextants or other equipment.

Peary’s Party, supposedly at the North Pole

We cannot rely upon the evidence that Cook or Peary brought back (photos of the North Pole and of the sun above the horizon) since these photos could be made from other locations besides the North Pole. Nor can we rely upon them identifying unique features of the North Pole itself, since the pack ice covering the North Pole is constantly drifting, carrying any flags, cairns, or messages with it. The best evidence of reaching the North Pole would have come from ocean soundings (lines used to measure the depth of the

sea floor). But Cook did not carry the equipment to make these soundings (claiming it was too heavy). Peary’s measurements ended at 1500 ft when he claimed that his line ran out, making them useless.

Peary party, making soundings on 7 April and running out of line at 1500 fathoms

Without clear proof, we are left with indirect evidence which leaves doubts about the claims of both explorers. The journals of both men show significant gaps and discrepancies. Cook did not appear to have much knowledge of the sextant which would have been essential in determining the location of the North Pole. His “proof of discovery” given to the University of Copenhagen did not include sextant calculations. When he included sextant information in his book, they were in error. Cook claimed to travel fifteen miles a day over the pack ice, a speed that exceeded previous expeditions over the polar sea (Fridjof Nansen, for example, averaged four miles a day). Peary, who was fifty-two years old and had lost most of his toes to frostbite, claimed to travel twenty-six miles a day for the last five days of his journey.

We will probably never know for sure if either man ever made it to the North Pole. One thing is certain though: their greatest legacy is not geographical discovery, but the controversy that they left behind. That we still talk about this issue, argue over its merits, and still try to figure it out, tells us more about ourselves, than the small spot they claimed to discover at the top of the world.

Profile: Frederick Cook

Maligned hero or con-man? A century after Frederick Cook returned from the Arctic claiming to be first at the North Pole, tempers still flare over his rightful place in history. Over the next couple of weeks, I will be featuring Cook in a series of posts. Some of these will feature work I’ve already done about the North Pole controversy in The Coldest Crucible. But some of it is me thinking out loud, preparation for the talk I’ll be giving about him next week at the North By Degree conference in Philadelphia.

Where to begin? In 1907, Cook traveled sailed north into the Arctic with big game hunter John Bradley. He returned in 1909 with a story for the presses. According to Cook, he crossed Ellesmere Land in 1908, and sledged up the coast of Axel Heiberg Land. From there, he claimed that he crossed the Polar Sea with two Inuit men, Etukishuk and Ahwelah, reaching the North Pole on 22 April 1908. This was first-page news in the U.S. and Europe. But the story would get even better. Rival explorer Robert Peary returned from the Arctic in the fall of 1909 also claiming to have reached the North Pole. When he learned about Cook’s claim, he told the press that the public had been handed a “gold brick.”

So began the “North Pole Controversy,” a debate that, much like the Democratic nomination process, never seems to end. Tomorrow’s post: The North Pole Controversy.

Storm Over Everest, Part II

Beck Weathers

On mountains and character: near the end of Storm Over Everest, Beck Weathers observes:

“Everybody always says that the definition of character is what you do when nobody is looking. And when we were up there, we didn’t think anybody was looking. And so everybody did pretty much what their inner person, the real them, the exposed them, would do.”

In an interview about the making of Storm Over Everest, David Breashears uses Weathers comment to consider the power of Everest to reveal a climber’s “core” person beneath the social artifices we show to the world (hat tip to Geoff Sheehy):

The idea is that all the artifice that we carry with us in life, the persona that we project—all that’s stripped away at altitude. Thin air, hypoxia—people are tremendously sleep-deprived on Everest, they’re incredibly exhausted, and they’re hungry and dehydrated. They are in a very altered state. And then at a moment of great vulnerability a storm hits. At that moment you become the person you are. You are no longer capable of mustering all this artifice. The way I characterize it, you either offer help or you cry for help.

This idea that the journey brings you closer to the person that you really are has long roots. We can trace it back to the Romantic movement in the late 18th century, when travelers set off into the wilds of nature in hopes of encountering “the sublime.” They sought to experience the beauty (and the terror) of nature, and in the process, learn more about themselves. No surprise that some of the most itinerant Romantic landscape painters of the 19th century headed to the mountains and/or the polar regions.

Frederic Church, Cotopaxi, 1862

We could also trace this idea back even further, to Petrarch’s ascent of Mount Ventoux in 1336. Petrach, an Italian poet who would come to embody the “spirit of the Renaissance,” used his hike up Ventoux (no oxygen required) to bushwack through the thickets of his own conscience. At the summit, he stated “I had seen enough of the mountain; I turned my inward eye upon myself.”

I have written, in The Escape From Civilization, how this idea surfaces in the works of Robert Dunn, who tried to scale Denali in the early 1900s with Frederick Cook. For Dunn, explorers were “men with the masks of civilization torn off.”

No doubt that mountains and other extreme environments create conditions that take us out of ourselves. Who can argue with Breashears that the hunger, cold, hypoxia, and sleep deprivation of Everest can make people act in ways at odds with their social personas? But what do we make of this? Breashears’ view – and that of Dunn and many others – suggests that the human psyche is a giant onion: tough, dirtied, and weathered on the outside, but pure at the core. Putting oneself in extreme enough environments, so this thinking goes, is a way to peel the onion and reach the true person underneath.

I don’t believe this. When you look at a person, when you look at yourself, where do you draw the line between artifice and real? My feeling is that what exists as “self” and “society” are elements we all carry inside of us which cannot be disentangled. We commonly think of “nature” and “nurture” as separate elements that influence the development of human beings – but think about it: can either of these elements exist independently of the other?

In any event, my point is this. Mountains are places to challenge oneself, to reflect, and find insight – certainly this has been their role in my life. But to say that they (or any environment) can burn away what is false from what is real doesn’t ring true to me.