Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationLet’s Get Geophysical

As some of you know, we are in the midst of the International Polar Year (IPY) 2007-2009, a global program to coordinate research in the Arctic and Antarctic. This IPY follows three earlier ones: in 1883-1884, 1932-33, and 1957-1958 (which was, technically, the International Geophysical Year IGY). The first IPY was the brainchild of Carl Weyprecht, an Austrian explorer who had grown tired of watching explorers race into the Arctic on bids to attain “Farthest North,” lose their toes to frostbite, then return home with pockets empty.

Carl Weyprecht

The “Race for the Poles” was, Weyprecht realized, a race but little else. As such, it was at odds with the needs of polar research, which required observers to stay in one place long enough to take note of what they were seeing, record measurements, and collect data. Only in this way would scientists begin to figure out how the polar regions functioned holistically, and then, how they influenced the rest of the world, particularly global weather and climates.

For over a century, science and transnational collaboration have been the twin pillars of the IPY philosophy. In combining them, scientists hoped, they could uncover the mysteries of the polar regions, all the while avoiding the need to subject their projects to the demands of the glory-hungry explorers and jingoistic leaders.

Yes, well, it was a lovely idea. In truth none of the IPYs were free from megalomaniacs (on sledges or in political office). During the first IPY, the United States outpost at Lady Franklin Bay, under the command of Adolphus Greely, dutifully collected research.

The Greely Party in 1881

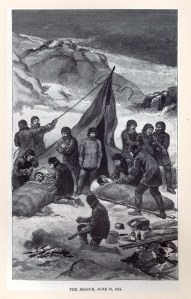

That is, until, Greely saw an opportunity to beat the record of “farthest north” held by the British. Two months of sledging and 600 miles later, Greely’s party established a new “farthest north” record of 83°24,′ exactly three nautical miles farther than the one set by the Nares Expedition in 1875. Science and latitude records were forgotten, though, with the expedition’s demise from cold and starvation. The failure of relief ships to reach Greely resulted in the deaths of most of his party. Nor did the spirit of the IPY carry on after the expedition’s rescue. The impressive pile of data collected by stations all over the Arctic could not compete with reports of Greely’s incompetence, evidence of cannibalism, and the execution of a crew member for stealing food.

The Greely Party in 1884

Fifty years later, an international meteorological congress tried to resurrect the idea of scientific collaboration with IPY-2, which took a new set of questions about magnetism, the aurora, and radio science, to the poles. Yet coming as it did in 1932, in the depths of the Great Depression, IPY-2 fell short when the money ran out.

The IGY of 1957-1958, conceived in the midst of the Cold War, seemed just the kind of feel-good, collaborative effort needed to reduce tensions between East and West. Unfortunately the first offspring of IGY was Sputnik. As the tiny satellite beeped its way over the Western hemisphere, it brought tears to the eyes of Russians, and visions of nuclear-tipped ICBMs to anxious Americans.

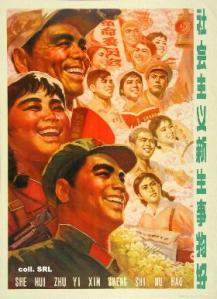

Despite talk of science and collaboration, then, the legacy of the IPYs has featured much of the vain-glorious and nationalistic pap that Weyprecht had been trying so earnestly to avoid. What then, can we hope to achieve in IPY-4? If my experience at the IPY-sponsored North By Degree conference is any indication, I think the ultimate benefit of getting people together is, well, getting people together. No one can offer a guarantee of future accomplishments. Most IPY subjects and discussions are too wonky to make good headlines. But ultimately the international IPY is a form of social communion, a way of building relationships. We had tense moments in Philadelphia – but we all stayed in the room – and continued to talk and argue about our positions for the extent of the conference. It is from this messy back and forth, I think, that real collaborative projects grow.

Digital Archive: Charles Darwin

Grave, sober Darwin. The melancholic Santa, staring out at us as if we were vandalizing his sleigh. This is the Darwin we remember: the tired revolutionary, the Devil’s Chaplin, a man so afflicted by ailments that he was a prisoner of Down House where he lived. Yet Darwin’s story — and the revolution he set off — grows out of his experiences as a youthful explorer, a roving naturalist aboard HMS Beagle.

HMS Beagle by John Chancellor

We already know about the Galapagos Islands, an iconic place in the story of evolution. But the voyage of the Beagle offered Darwin many experiences that raised questions: why did the giant fossil remains of South America resemble species still living there? Why would God create two separate species of flightless birds, the Rhea and the Ostrich, on separate continents instead of just one? So much has been said about Darwin (and some of it, especially by Janet Browne, has been said so well) that I don’t feel like saying more.

Rheas

Except that there is a website that every student of exploration should know about: The Complete Works of Charles Darwin Online. It is not simply that you can read virtually every published word that spilled from His Most Worthy Naturalist’s pen (and most of the unpublished words too), but also that you can see how Darwin’s life and work were closely linked to the work of other scientist-explorers. Here are hundreds of notes, letters, and references to Alexander von Humboldt (South America), Joseph Dalton Hooker (Himalayas), Thomas Huxley (New Guinea and Australia), and Alfred Russell Wallace (Malay Archipelago). If you find yourself moved, (perhaps mutated) by the experience, your next click should be on The Dispersal of Darwin, a blog for fans, scholars, and committed Darwinistas.

The 20th century biological revolution which was ushered in by Watson and Crick (and, it should be remembered, Rosiland Franklin) have given us a new image of the biologist as lab scientist, complete with black rimmed glasses and pocket protector.

Watson and Crick: Smart, Not Outdoorsy

Let us not forget that the 19th century revolutionaries were a stunningly itinerant bunch, surveying species and ecosystems all over the globe. Darwin, in particular, was not afraid to get his boots dirty. We should remember this when we see images of the shuffling grand old man of science.

See also Darwin in Four Minutes

Visit the sites:

The Reenacted Voyage

SSV Corwith Cramer

In May 2006, I sailed out of Key West aboard the SSV Corwith Cramer, a 134 ft steel brigantine belonging to the Sea Education Association. With 7800 square feet of canvas, the Corwith Cramer looks like it sailed out of a painting by Fitz Hugh Lane. Yet it is a modern craft, fully outfitted for research, complete with bathymetric equipment, hydrographic winches, biological sampling equipment, sediment scoops, and rock dredges. Not that I would know the difference between a scoop and a dredge. In my former career in science, the mysteries of life were something best looked at indoors, preferably under a laminar flow hood where they wouldn’t infect you.

The Laminar Flow Hood

Today my research questions are different. They focus on humans rather than marine ecology or rarefied microbes. And it was the human element of the voyage that made the its greatest impression on me, namely my own halting adaptation to life aboard ship. As the Cramer’s B squad, we worked in eight hour watches, manning lookout, checking the weather, hoisting sail, and swabbing the sole. My berth was above the table in the galley, so I had to step over people eating (day and night) in order to get anywhere else in the ship. I slept three to four hours at a time, bathed in sweat. It was a breathtaking, bewildering, exhausting experience.

Crow’s Nest, Corwith Cramer

It was, nevertheless, an experience which affected my research, because it showed me, in a way I never really understood before (reading books in the archives), the profoundly exhilarating and unsettling nature of life on a ship packed with officers and crew. Suddenly it seem didn’t odd that scientific specimens disappeared or disintegrated before making it back to the metropole. It didn’t seem odd that Pacific and Polar expeditions so often ended in mutiny or violence. (Not that we had mutiny on our minds. The crew of the Corwith Cramer was friendly and professional. I’m just projecting what it would be like to be on such a vessel for years at a time, with a larger crew, smaller berths, no fresh food or refrigeration, few links to the outside world, mixed together with the occasional bout of scurvy). Nor did it seem odd that explorers sometimes stayed in touch with former shipmates forty or fifty years after the end of the expedition. While the Corwith Cramer bore no resemblance to the the Fram, the Beagle, the Endeavour, or any other famous crafts of discovery, it gave me a way of understanding some of the events that took place on these vessels long ago.

For me the reenacted voyage offered inspiration, a way of seeing, in a new light, historical events. But this is not alway the objective of such voyages. Maritime adventurists often find a different inspiration in the reenactment, principally to recreate earlier events. For example, Philip Beale, leader of the Phoenician Ship Expedition, plans to sail a 21 meter square rigged ship around Africa in hopes of showing that the Phoenicians accomplished this route in 600 BC.

The Good Ship Phoenicia

As Beale put it in a Reuters interview:

“”The Europeans think it was Portuguese explorer Bartholomew Dias who did it first. But I think the Phoenicians did it 2,000 years earlier and I want to prove it.

And on his website:

“The Phoenicians obviously conquered the Mediterranean, but did they really go all the difficult and long way around Africa? That is the question.”

That is indeed the question, but one that Beale will be no closer to answering after the Phoenician Ship Expedition sets sail. Phoenicians may or may not have sailed around Africa, but Beale could never recreate the voyage with any accuracy because he knows where he’s going and how he’s going to get there, something that the first Phoenician navigators would not have known. Indeed, 14th century Venetians had a much better sense of the African coastline and Atlantic currents, but still feared passing beyond Cape Bojador (on the West Coast of Africa) because they’d be sailing against the current on the way back.

Another example: in 2005, British trekker Tom Avery sledged with to the North Pole in 36 days, a feat that he claimed “rewrote the history books” because it proved Robert Peary could have made it to the North Pole in 37 days as he claimed in 1909. While there may still be doubters, Avery hopes “that we have finally brought an end to the debate and that Peary’s name will be restored to where it belongs in the pantheon of the great polar explorers.”

Avery, channeling Peary, at the North Pole

But Avery’s expedition differed from Peary’s in significant ways. Avery was a robust 29 when he reached the North Pole. By contrast, Peary was 52, hobbled by the loss of eight toes, and suffering from a variety of ailments. Avery could afford to pack light on his trip since he didn’t have to make a return trip back to land (his party was airlifted from the North Pole shortly after he arrived). Peary, by contrast, had to slog his way back under dog power.

Beale and Avery, I’m afraid, have succumbed to Kon-Tiki Syndrome, a state of mind in which reasonable explorers start believing that they are the philosopher’s stone, agents with the power to transform reenactments into the gold of historical proof. I am a great believer in such voyages as experiential education, but they have no value in telling us what really happened in the past. Unfortunately there are no shortage of adventurers and sponsors willing to organize such expeditions. What to do. Blame Thor Heyerdahl.

Famous Falling Objects

An update on Saturday’s post: The Mars Phoenix Lander successfully touched down on Sunday and has started unpacking its bags. Like any good tourist, it has started taking pictures of itself.

It’s also taken some lovely shots of the polar surface. They show a delicate pattern of polygons etched into the dirt, strongly suggesting the presence of water.

Michel Fournier has had less luck on his quest to become the first human meteor. On Tuesday, his crew began filling up the massive balloon that would be used to carry him to 130,000 ft. But for unknown reasons, the balloon decided to leave without him. After shooting upwards, it began to lose helium, eventually plummeting to earth, tearing itself to shreds on the way down.

I am not sad to see this mission fail. As I mentioned in my earlier post, Fournier’s seems like a project better designed for spectacle than science (though, as a student of the history of science, I admit the line is blurry). Fournier gets points for bravery. And this kind of jump had serious application once, in the early days of space flight, when no one knew what would happen to astronauts bailing out at high-altitude. But at 64, Fournier hardly offers science the best physiological model of a 35 year old astronaut. More to the point, for this sort of testing has been done before. Fifty years ago, Joseph Kittinger set a jump record of 96, 760 ft as part of the Man High I Project. In 1960, he set the altitude jump record that still stands: 102, 800 ft. Now, Fournier will have to decide if he really wants to continue with “Le Grand Saut,” as they call it in French, or “The Man Seriously High Project” in the lower 48.

Col. Joseph Kittinger’s seriously high jump in 1960

North By Degree

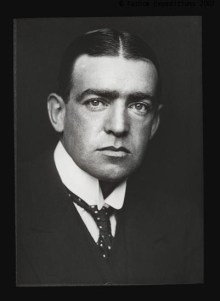

Ernest Shackleton

If I had to guess, I’d put the current readership of books on Ernest Shackleton at about three billion. This number will surely grow to include all members of our species once the corpus of Shackletonia has been fully translated into Chinese. Those of us who have etched out a living writing about other polar explorers smile and try not to be bitter. We make do writing articles for hard-to-pronounce journals, publishing books with tiny print runs, and giving talks at libraries and retirement homes.

Waiting for the new Shackleton biography

But there are bright moments working in the shadows of Shackleton. We, the scholars of the obscure, have a keen sense of fellowship. We know the twenty or so people out there who do the same thing we do. In polar exploration, this society of scholars includes: Russell Potter, Lisa Bloom, Kenn Harper, Peter Capelotti, and Robert Bryce. I have gotten to know these writers through their work: The Fate of Franklin, Gender on Ice, Give Me My Father’s Body, By Airship to the North Pole, and Cook and Peary. As I wrote The Coldest Crucible, I spent a good deal of time figuring out how my work connected to theirs. But for all of this, I had never met any of them.

Last week they were all there, the Arctic All-Star Team, talking shop and drinking coffee at the North By Degree conference in Philadelphia. I met other members of the fellowship as well, among them: Susan Kaplan, Bob Peck, Christina Sawchuk, Karen Routledge, Rob Lukens, Patricia Erikson, Anne Witty, Chip Sheffield, Stephen Loring, Elena Glasberg, Laura Kay, Lyle Dick, Emma Bonanomi, Christyann Darwent, Erik Sundholm, Russell Gibbons, David and Deirdre Stam, Huw Lewis-Jones, Kari Herbert, Genevieve Lemoine, Frederick Nelson, Helen Reddick, and modern explorer and polymath Tori Murden McClure, who gave a terrific talk on the motives of exploration.

We weren’t all cooing and nodding at each other, either. There were some good scuffles: over the Cook-Peary controversy, gender and exploration, and our different approaches to history. I’ll be featuring more tidbits from the conference over the next month or so. Maybe we can generate a good dust-up here as well.

Discussing Polar History