Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationBook Review: The Oxford Companion to Exploration

The Oxford Companion to World Exploration, ed. David Buisseret (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007)

The Oxford Companions are strange creatures, neither fish nor fowl. Outwardly they resemble the cross between a dictionary and encyclopedia. But this description doesn’t quite do them justice. A companion, after all, is something or someone with whom we have a relationship, a bond that transcends that of a mere guide or reader. In a review of the Oxford Companion to Music, David Schiff points out that a companion “implies something more intimate and less predictable… informed but not infallible, quirky, opinionated, worldly yet parochial.” This is a lovely notion in principle, but could easily turn out to be a mess in practice. Fortunately, the companion format proves liberating for editor David Buisseret, who, with a team of section editors and advisors, has developed a creative fusion of subjects, from short biographies of 250 words to comprehensive pieces of 10,000 words or more.

David Buisseret

Buisseret brings a big-tent philosophy to Companion, helped, no doubt, by his wide-ranging research on cartography and exploration, and his twenty years of experience as editor of Terrae Incognitae, the journal for the history of discoveries. “We have defined [exploration],” Buisseret writes, “as the process by which one or more people leave their society and venture to another part of the world (or, now, heavens), then return in order to explain what they have seen.” This is about as expansive a definition for exploration as one can give, and would probably include my own travels abroad (I do not receive an entry). As a result, the 700 entries of the two-volume Companion consist of a heterogeneous mix of subjects, from the famous (Christopher Columbus, Antarctica, Sputnik) to the obscure (Odoric of Pordenone, Chinese Empirical Maps, Quiviria). Serious readers of exploration will find two features useful. First, Companion provides comprehensive surveys of exploration in all major geographical regions (Africa, Arctic, Pacific, etc). Each of these is broken up into sub-entries that provide useful detail and context. Under the entry “Central and South America,” for example, the reader finds subentries on: “Colonies and Empires,” “Conquests and Colonization,” “Scientific Inquiry,” “Trade and Trade Goods,” “Trade Routes,” and “Utopian Quests.” Second, Companion offers a number of sophisticated thematic entries on exploration, such as “Alterity,” “Imperialism and Exploration,” and “Fictions of Exploration,” which touch on issues that will be of interest to academic audiences. The Companion does have its weak spots. Major entries use multiple authors for each subentry which often leads to some repetition of material. Obscure explorers (such as polar adventurer Charles Hall) sometimes receive their own entries whereas major explorers (Robert Peary, putative discoverer of the North Pole) do not. Moreover, inclusive does not mean exhaustive; any companion on world exploration should come prepared to weigh in on the “Grand Tour,” “Noble Savage,” and “Contact Zone.” An entry on the last term would be especially welcome since “Contact Zone,” coined by Mary Louise Pratt in her 1992 work Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation is now used by many in the academy as a conceptual upgrade of the Eurocentric term “Frontier.” It would also show that Buisseret means it when he tells us of his “struggles against the European connotation of the word [exploration].” Still, it is too easy to take pot shots at anything this expansive and multi-authored. All in all, Companion is a very useful reference book, especially given its slim, two-volume size. If it doesn’t take the reader to every corner of the field (what volume could?), it comes with an excellent system of navigation: table of contents, topical outline of entries, directory of contributors, index, and seventy-five colored plates. Ironically, its ease of use only makes one feel guiltier for enjoying it. Browsing its pages, feet up, sipping tea, the reader confronts the some of the most arduous events in human history.

This review will be published in the upcoming issue of the British Journal for the History of Science. My thanks to Simon Schaffer and Gregory Radick for permission to reprint it here.

The Beagle Project

HMS Beagle, famous ride of Charles Darwin, now rots quietly on the bottom of the River Roach. But if The Beagle Project is successful, the storied ship may sail again, retracing its famous round-the-world route from 2009-2011. In the words of Beagle Project organizers:

We aim to celebrate Charles Darwin’s 200th birthday by building a sailing replica of HMS Beagle and then retracing the 1831-1836 Voyage of the Beagle with an international crew of researchers, aspiring scientists and science communicators. The new Beagle will symbolise both the physical and intellectual adventure of science; she will be equipped with laboratories, 21st century science equipment and satellite communications, she will host cutting-edge science projects of international relevance while serving as vehicle for improving wider public engagement with and understanding of science.

The Beagle Project exemplifies what I think is best about reenacted voyages (something I wrote about two weeks ago). While some reenact expeditions in hopes of proving historical points (e.g. sailing an ancient Phoenician ship around Africa to “prove” that Phoenicians did it first) others sail to experience life aboard ship, and hopefully, insight into particular aspects of the original voyage. The Beagle Project is very much an enterprise of the latter variety – a voyage which will sail between the worlds of history and the present day. Meanwhile, the scientific crew of the new Beagle will be pursuing a variety of projects including metagenomics and DNA barcoding.

In other words, this is a project that deserves support. If you aren’t convinced, consider the money now pouring into anti-Darwinist reenactments. Millions have been spent on Kentucky’s 60,000 sq ft. Creationist Museum and Florida’s Dinosaur Adventure Land, venues that base their historical reenactments on the Old Testament rather than geological or biological history.

Close your eyes now and imagine your children walking through the Creationist Museum’s Garden of Eden diorama. Now they’re off to the humans-living-with-dinosaurs exhibit. Soon they’ll be at the gift store, emptying their pockets to buy “4 Power Questions to Ask an Evolutionist.” Now open your eyes, wipe the sweat off your brow, and give generously to the Beagle Project.

Humans Frolicking with Dinosaurs at the Creation Museum

Keep up to date with expedition plans at The Beagle Project Blog.

The Discovery of France

The muse is a strange bird. We try to ignore it, focus on the work at hand, and remember the mantra that “ninety percent of any project is hard work.” (The Puritans must have coined this phrase. Or Reader’s Digest? Joseph Stalin?). The muse leaves me alone in these moments of productive toil, waiting until I am without pencil or palm pilot, usually in the shower or out running in Elizabeth Park. These are, for some reason, my brightest moments. There must be a good psychological explanation for this. Whatever it is, these places form the mystic triangle of my intellectual life: study, shower, park.

But it was my son Theo who played muse yesterday. We were at the public library and I was headed downstairs with my kids when he broke away, running towards the New Books Section with the lurching gait common to 18-month-old children and drunken elderly men. I caught him in New Non-Fiction, and stood there long enough to notice Graham Robb’s new book, “The Discovery of France.”

I’m only 40 pages in, but have seen enough to realize how nicely Robb’s project connects to the ideas of exploration I wrote about in my last post. To recap: the modern era (1789-present) is filled with those who have viewed exploration narrowly as the engine of geographical discovery, a way to put people in places where they haven’t been before (or, if that’s not possible, to put white people in places where white people haven’t been before).

Anglo-American Hunters in Africa

Yet there have always been critics of this view from 19th century figures such as Alexander von Humboldt and Simon Bolivar to 20th century historians such as William Goetzmann. Why do we care? Many reasons. But perhaps the most compelling one is this: how we think about exploration shapes our policies on exploration. Specifically, the goal of putting humans in places they’ve never been before has gotten more difficult and more expensive. Designing craft that can hurl living beings into space and then return them, still breathing, to earth requires gargantuan sums of money. As such, they suck the life blood out of smaller, more useful, scientific projects that would give us a better, holistic, and more integrated understanding of our solar system.

People on Mars: Expensive

Robots on Mars: Cheap

Robb’s project has nothing to do with space. But it has everything to do with re-conceiving exploration in its broadest terms. We, the scholars of the voyage, usually apply our questions to westerners who are mucking around (and mucking up) places far from home. In this case, Robb – adopting a Humboldtian perspective – turns the question upside down: how do civilized societies explore their own backwaters and terrae incognitae? Specifically, how does rural 18th-century France appear when viewed through the looking-glass of the Enlightenment explorer? Robb’s answer: exotic at best, savage at worst, always dangerous, sometimes violent. At the moment when Versailles is sending expeditions to measure and catalog the world (by Condamine, Bougainville, and La Perouse), it is woefully ignorant of regions a carriage-ride away from Paris. It was here, in these rural regions of France that Jacques Cassini sent out observers to complete a massive survey of France and here, Robb observes, that “on a summer’s day in the early 1740s, a young geometer on the Cassini expedition was hacked to death by the natives.”

Gaul: Dangerous Country

But there is more to Robb’s project than this grisly, if delicious, irony. His book exposes the limits of one line of thinking that had become too popular in the academy, namely that exploration was a monolithic enterprise, the eager forward guard of empire, ruthlessly and efficiently preparing the way for conquest and colonization. Admittedly, there is some truth to this. But it is hard to believe that European empires were monolithically controlling anything when we learn that Paris was scarcely more in control of the province of Savoie than its far-flung colony of St Dominigue. For those who’ve drunk deeply from the well of Foucault and Said, this is something to take seriously. The “gaze” of the scientist alighted on many objects, local, as well as global, white as well as native. The pompadoured aristocrats of Paris found their “others” not only in souks of Cairo, but among the shepherds of the Pyrénées.

What is Exploration?

You would think I’d have figured this question out after so many years of working on it. To be honest, I don’t feel any closer to an answer than I did twelve years ago when I began a field in the history of exploration for my prelim exams. The shortest, least satisfying (and dare I say, most academic) of answers would be to say that, well, it depends.

Some think of exploration as the investigation of unknown regions, a capacious view that extends to the voyages of Christopher Columbus as easily as those of Alexander von Humboldt or Lewis and Clark. Others have given it a more precise meaning. As the OED declares, Exploration is an activity “for the purpose of discovery.” This is the view adopted by William Goetzmann in his path-breaking book Exploration and Empire (1966). In Goetzmann’s words, Exploration “is purposeful. It is the seeking. It is not the mere happenstance of discovery which “can be produced by accident.” This may not seem like an earth-shattering distinction, but it would probably be enough to cast Columbus out of the sacred pantheon of explorers. He wasn’t, after all, as interested in discovering new lands as he was finding new routes to old ones. I imagine that Columbus would have been rather peeved to learn that his West Indies were no where near Asia. Fortunately he died before Magellan figured this out.

I know where I am

There are other ways that exploration means different things to different people. Many popular books on exploration treat it, more or less, as the engine of discovery, a process that culminates in the “First Footprint” (if no one is around) or the “First Encounter” (when inconsiderate natives have left footprints of their own).

But to others, these firsts are only the beginning of a longer, systematic process of investigation which may continue for years after the initial geographical discovery. Arriving in South America in 1799, one could say that Alexander von Humboldt was about 300 years too late for discovery. He spent four years trekking through South and Central America, botanizing and criticizing the Spanish regime. Such was the influence of Humboldt that Simon Bolivar called him “the true discoverer of America.”

Simon Bolivar: Revolutionary and Humboldt Groupie

A century later, Hugh Robert Mill would voice similar views:

As exploration proceeds, and as it is followed up by detailed scientific study, wave after wave of knowledge flows over the earth’s surface, each forming, as it consolidates, the ground upon which the next will spread. (Mill, McClure’s Magazine (Nov 1894) 3:540)

Stated somewhat differently, Goetzmann applies this view of exploration to the American West:

The country beyond the Mississippi, as we now know it, was not just “discovered” in one dramatic and colorful era of early-nineteenth-century coonskin exploration. Rather it was discovered and rediscovered by generations of very different explorers down through the centuries following the advent of the shipwrecked Spaniard Cabeza de Vaca. (Exploration and Empire, x)

Differences in the meaning of exploration may seem like so much academic bean-counting, but they have serious consequences. One imagines, in reading George Bush’s 2004 Vision of Space Exploration, that the image of an American bootprint in the cold, red dust of Mars figured strongly in his calculations to ramp-up human exploration of the solar system.

Other space scientists, however, have watched this NASA directive play out with alarm. As science budgets get cut to make room for new launch and crew vehicles (on this see this post as well as this one), the Bolivarian view of exploration gets sacrificed to “we got there first.”

On ideas of exploration, see also:

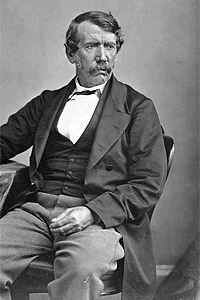

Digital Archive: Livingstone Online

As someone more familiar with explorers from this side of the pond, my encounters with David Livingtone, British missionary and African explorer, have been mediated by others: biographers, Henry Morton Stanley, or the press reports of the New York Herald. No longer is this the case. Professor Christopher Lawrence of the Wellcome Trust Centre of the History of Medicine has established Livingstone Online, a place where you can read Livingstone’s own words, primarily letters from the holdings of Wellcome and other archives in the UK. Livingstone Online also offers good contextual background on science and medicine in 19th century British society. Taken together with Google Book’s collection of full text Livingstone works (including Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa), we now have the key sources to uncover the man (if not, alas, the Nile).

Listen to Chris Lawrence discuss the Livingstone project here.