Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationUncharted Waters: A Skeptic’s View of the latest search for the lost ships of Sir John Franklin

By Russell A. Potter

http://www.ric.edu/faculty/rpotter/sjfranklin.html

The news is currently making the rounds that another, bigger and better search for the lost ships of Sir John Franklin is being mounted by the Canadian government. There’s some historical irony here – since “bigger” and “better” were the very words used to underpin public confidence Franklin’s original expedition when it first sailed – and we all know how well that turned out. Nevertheless, there are some modest auguries of success with the present expedition, though nothing quite as grand as the press releases would suggest; even when looking for a needle in a haystack, there is something to be said for looking where others have not looked before, and having more people doing the looking.

The chief reason given for the launch of a new search at this time is historian Dorothy Eber’s account of fresh evidence from Inuit oral traditions, as well as the discoveries of modern-day Inuit themselves. Eber’s evidence, gathered together for her upcoming book Encounters on the Passage: Inuit Meet the Explorers (University of Toronto Press), is unusual in that most of it dates to the past forty years, a time when the oral traditions of the Inuit have been interrupted by resettlement, loss of language, and enormous changes in everyday life. True, the elders still preserve an enormous wealth of traditional knowledge, but when it comes to recollections of specific historical events, the continuity of that tradition has been severely compromised. The principal witnesses of the fate of the Franklin expedition, it should be recalled, were actually quite few in number – the party of three hunters who encountered a group of survivors at Washington Bay were the only ones to speak with the living – and many of the eyewitnesses were members of Inuit bands, such as the Utjulingmiut, whose members were already scattered and displaced when they spoke with John Rae at Repulse Bay in 1854. The echoes of that tradition, such as they are, are faint indeed, and in many instances in Eber’s book, it’s not quite clear which among these new accounts can actually be definitely identified as stories of Franklin’s party.

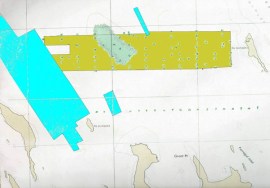

Almost all of the Inuit testimony agrees that one of Franklin’s ships was deliberately anchored, and her gangplank lowered, somewhere in the vicinity of Queen Maud Gulf, most likely on the western shores of the Adelaide Peninsula. This is the area where David C. Woodman, the foremost modern interpreter of the Inuit testimony, has been searching for years despite limited funds and resources. Through his labors areas near Kirkwall Island and O’Reilly Island, two sites which match the early Inuit stories, have been fairly exhaustively searched, but represent only a small percentage of the overall area associated with the Inuit tales. The present search will be led by Robert Grenier, lead archaeologist for Parks Canada, who caught the Franklin bug while working with Woodman. Initially a skeptic of Inuit testimony, Grenier was impressed by finds of sheet copper and other nineteenth-century relics at sites identified by Woodman as those in the Inuit stories.

He has now, apparently, linked these to tales recounted by one of Ebert’s informants, who believed that the remaining ship was in fact further west, in the vicinity of the Royal Geographical Society Islands. Unlike Woodman, who believes Inuit accounts of the ship having been deliberately anchored, Grenier says in his proposal that the ships may have drifted to this location, or run aground.

As suggestive as it is, the testimony about the RGS Islands site is one of several accounts in Eber’s book, others of which are quite different, and even mutually exclusive. Some even suggest that one of Franklin’s ships attempted to sail around the eastern shores of King William Island, the opposite of what has always been believed to be their route. These stories seem to be based not on sighting of ships, but of debris and cargo. A more likely explanation lies in a substantial amount of material tossed overboard by Roald Amundsen near this point in order to enable his ship the Gjøa to ride higher in the water, and thus navigate the shallows – but in the ice-floes of such a long tradition, keeping one story distinct from another is as treacherous as navigating a strait far narrower and more convoluted that that where these boxes of supplies were found. For a Franklin researcher such as myself, Eber’s book makes for fascinating reading, but as a guide for archaeological searches it may prove frustrating.

Another source of evidence has been provided by contemporary Inuit searchers, such as Gjoa Have resident Louie Kamookak. Kamookak, who some years ago led the crew of the St. Roch II expedition to human remains near the Todd Islets on the south coast of King William Island, is to be part of Grenier’s new search. The bones located by Kamookak, however, had actually been found many years previous; their location was known to Hall (although snow prevented him from seeing much), and the entire site was gone over by William Gibson in the 1931, who located and reburied some skeletal remains. Kamookak simply did the modern searchers the favor of reminding them of something they actually already knew. Of course it is vital to include Inuit in the search for an expedition that involved their ancestors, and in the recounting of the history of the Franklin era – but there’s not necessarily any special knowledge of this period among Inuit today. A coordinated search of all known Franklin sites and reports might be better begun in a research library than in the Arctic itself, at least if the findings of the past are not to be needlessly repeated.

All of which illustrates the difficulty of using Inuit evidence to limit the area of one’s search – there are so many tales, so intertwined, that it’s nearly impossible to separate one sighting of “Kabloonas” from another. This is a difficulty which Grenier’s party may find slightly less daunting; with more resources to deploy, a wider area can be searched, and precise accuracy may be less important. The unusually good ice conditions these past few seasons have also opened up areas for searching by ship that were formerly rendered inaccessible by heavier coastal ice. If indeed, as the Inuit stories traced by Woodman recount, the lost vessel was at anchor, and sunk at its moorings in an area shallow enough that the tops of the masts were still above water, then there may be some hope that the hull of the vessel is largely intact, supposing it could be found.

And yet, if it is, it will be the preponderance of the Inuit testimony – and the courage of researchers such as Woodman in trusting it – rather than any new bit of information, that should be credited with the find. If you look back far enough, in fact, it’s really Charles Francis Hall who deserves the ultimate credit – for it was he, during a time when most Europeans and Americans discounted the word of the Inuit as the “vague babble of savages” (the phrase is Charles Dickens’s) who continued to collect, and to implicitly trust, the accounts of the Inuit people of the fate of Franklin’s men. In his tiny, folded “field notebooks” from the 1860’s – preserved at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. – lie the original accounts, carefully translated by his faithful guide Tookoolito, upon which the hopes of present searchers most greatly depend.

Recommended Links:

The Fate of Franklin

http://www.ric.edu/faculty/rpotter/sjfranklin.html

David C. Woodman’s Search Pages (at my Franklin site): http://www.ric.edu/faculty/rpotter/woodman/mainpage.html

Inuit Testimony about Franklin, collected by Hall, Schwatka, and Rasmussen:

http://www.ric.edu/faculty/rpotter/inuittest.html

Robert Grenier’s original IPY Proposal for the new search

http://classic.ipy.org/development/eoi/proposal-details.php?id=330

The Birth of Exploration

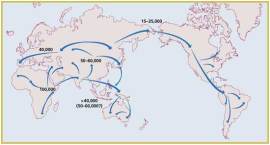

When did exploration begin? A difficult question. If we consider exploration in its broadest sense as an activity that takes people to places they’ve never been before, then we have to start very early indeed. Evidence suggests that hominids left Africa in a series of migrations over millions of years. If we limit ourselves only to homo sapiens sapiens, we still have to go back 50,000 or 60,000 years, the time when many sorts of evidence suggest a small population of humans left Africa, probably without a road atlas.

But perhaps we should narrow our definition a bit. Most of us now think of exploration as something more than mere migration, something that includes a self-conscious pursuit of the unknown. If this is our definition, we need to start much later. How much later is hotly debated, perhaps as late as the 14th or 15th century CE.

Even this starting point has problems. First, many Renaissance explorers like Columbus were not primarily interested in discovery of unknown regions, but hoped to find new routes to known locations such as Cathay (China) and the Spice Islands (Indonesia). On this see my earlier post. Second, terms such as “explorer” were not yet used to describe people who set off in search of discovery. For all of their impressive nautical muscle-flexing, Columbus, Cabot, Hudson were viewed as “travelers,” and their voyages, “travels.”

By the 1800s, however, the umbrella of “travel” had become very large indeed. Not surprisingly, the idea of the traveler was also in flux, a category that had come to encompass every itinerant from Joseph Banks, science officer of the Endeavour, to British lads on vacation. As the concept of traveler lost definition in the eighteenth century, “explorer” entered the vernacular to delineate it, to distinguish the serious investigator of the unknown from more quotidian voyagers, the doe-eyed ingénues of the Grand Tour.

So we could start our study of modern exploration in 1800. A very judicious decision. Except that we would be basing this starting point on the use of words, “explorer” and “exploration,” rather than a shift in thinking or practices. This is not very satisfying either. Certainly ideas about mapping unknown regions have been around a long time, even if they were called something else.

In his excellent book The Beginnings of Western Science, David Lindberg identifies a parallel problem for the history of science. If words like “science” or “biology” constitute one’s starting point for modern science, then the historian begins her task quite late, in the nineteenth century. If she considers scientific ideas or methods to be the key, then the starting line could be pushed back into the early Renaissance. But even this date ignores the work of earlier scholars (naturalists or philosophers we might call them) who spent their lives trying to understand the functioning of nature deep into recorded history, say 600 BCE.

In short, no starting point is perfect. One thing is clear though; the relationship between exploration and travel is too strong to be ignored. It might sound easy to group them together, but for scholars of the voyage, this can be more difficult than it appears. The division that grew up between these concepts in the 19th century has also come to define a modern boundary of sorts. The subject of exploration attracts many scholars today, with historians probably represented in largest numbers. By comparison, the study of travel, particularly travel writing, has become a favorite subject of literary and cultural studies scholars. One sees this division in the academic journals and websites devoted to travel vs. scientific exploration.

So in the next few months I will be doing some exploring of my own, wading into the travel literature from the other side of the disciplinary fence. In the meantime, if you are interested, I’ve put up some links on travel writing.

Announcements

Maurice Isserman, professor of history at Hamilton College, writes an interesting op-ed about K2 in the Sunday New York Times, describing the changing ethos of mountain climbing over the past 50 years. He compares the tragedy on K2 last week, in which everyone was trying to save themselves, to the American attempt on K2 in 1953, when an entire party abandoned their efforts at the summit to save one member who was suffering from potentially lethal blood clots in his leg.

The Scott Polar Research Institute is putting on an exhibition called “Face to Face: Polar Portraits.” The show includes portraits and profiles of over one hundred Polar explorers, including a companion volume edited by Hew Lewis-Jones (who’s talk at the North By Degree conference was first-rate).

The Giant’s Shoulders, a new history of science blog, is organizing a monthly carnival in which people submit posts about classic scientific papers. Hosts for the event change each month. For the latest carnival, head to The Lay Scientist on August 15th.

In 2009 International Conference on the History of Cartography will be meeting in Copenhagen to discuss papers on “Cartography of the Far North: Maps, Myths, and Narratives.” 1 October 2008 is the deadline for submissions. See the Call for Papers and other information here: ICHC 2009

A Place to Plant the Flag

Thanksgiving, that magical day, a time of gathering, fellowship, and unrestrained serial eating. Like all holidays, Thanksgiving unfolds in the present, tethered in complicated ways to the past. “Tradition” probably best describes these personal, historical, links. Consider turkey. We eat turkey in our house because we like it, it keeps well, and can be transmuted into any number of post-Thanksgiving dishes: turkey soup, turkey sandwiches, turkey fricasse. But turkey remains on the menu every year not only because of its tastiness and longevity, but because it’s always been on the menu, seared as it is into the mystic chords of turkey memory. I cannot think of a time when we considered having something else for Thanksgiving. Such is the power of tradition.

Exploration has its own traditions, ways that link current endeavors to historical precedents. Some of these traditions are obvious enough, such as the naming of vessels, probes, etc. in honor of previous people or ventures: Galileo, Cassini, Enterprise, and Challenger. But others are more difficult to detect without hindsight. Many explorers prided themselves on being careful empiricists, objective observers of the regions they described. Reading these works now, however, its hard to miss the imprint of culture on their narratives, the martial descriptions of exploration as a “war on nature” and the kindly, patronizing descriptions of native peoples as “children of nature.” These tropes were also traditions of a sort.

Yet some things are still hard to see with the benefit of hindsight, even when they are staring at you in the face. Consider Dan Lester and Giulio Varsi’s article at the Space Review on the current Vision of Space Exploration. Lester and Varsi observe that NASA’s tradition, implicit (perhaps unconscious?) has been to associate exploration with solid places, rocky grounds suitable for “footprints and flags.” There are good reasons for going to the Moon and Mars, particularly for astrogeologists who want to know more about, well, the Moon and Mars.

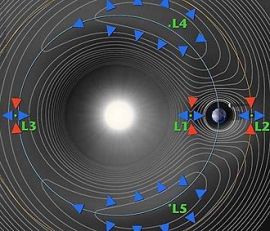

But what about those scientists who seek to uncover more about the broader galaxy? This is a form of exploration best conducted remotely, with telescopes, rather than suited-up astronauts. For these purposes, the Moon and Mars are not ideal locations. To get the most bang for the buck, telescopically speaking, NASA would send its space telescopes to one of a number of “Lagrange points,” regions of space where telescopes could remain stationary relative to larger objects such as the Earth and Moon. Freed from planetary surfaces, these telescopes could observe broad reaches of the sky, unencumbered by planetary atmosphere or blind spots.

Costs and operational simplicity seem to favor by a large margin locations in free space such as the Earth-Sun Lagrange points over the lunar surface. While lunar soil may offer a record of solar activity that is valuable to heliophysicists, realtime monitoring of the Sun and the solar wind does not need to be anchored on regolith. Overall, the lunar surface presents a challenging environment, with dust and power generation problems as well as the difficulty of precision soft landing.

Relative to the push for human exploration of the Moon and Mars, “Lagrangian exploration” is a low priority for NASA. Why? Perhaps, as Lester and Varsi observe, it’s because of the historical importance of discovering land, of sinking one’s feet into the soil and then planting a flag in it.

As I read this article, it suddenly made other pieces of historical data fall into place. When Robert Peary and Frederick Cook brought back their photographs of the North Pole, why did both men choose to plant their flags in the highest hummock of pack-ice they could find? No such location would have been identifiable so precisely from astronomical calculations (if indeed either of them reached the North Pole, which I doubt). Clearly then these men had other reasons to plant the Stars and Stripes on a high hummock, rather than, say on a flat stretch of pack ice or floating on the water of a “lead.”

Clearly “earthiness” remains a tradition in exploration, an element that remains in the western imagination of discovery. When the nuclear ice-breaker Yamal steamed north in 2000 with its burden of high-paying tourists bound for the North Pole, it found open water there. What to do? The party could have celebrated the watery top of the world from the deck. Paddled around it in inflatable boats! Instead the Yamal steamed south far enough to reach solid pack ice. There the crew planted the “North Pole” flag around which the passengers danced, celebrating their attainment (kind of) of the top of the world.

Maybe its time to break tradition.

Tragedy on K2

It now appears that eleven climbers perished Sunday on K2, the world’s second highest mountain. K2 is steeper and rockier than Everest and more prone to changeable weather. That makes it, in climbing circles, the mountaineer’s mountain. But I fear that this is about to change. In 1996, a number of climbers lost their lives on Everest, an event made famous by Jon Krackauer in his book Into Thin Air. Krackauer’s book was fiercely critical, not only of the actions of fellow climbers, but of a new selfish ethos that pervaded the culture of Everest. Yet new accounts of the Everest industry, by Michael Kodas (High Crimes) and Nick Heil (Dark Summit), show that the mounting body count on Everest has done nothing to slow the march of “clients” pouring into Base Camp. Indeed, the number has increased.

Arctic exploration exhibits a similar phenomenon. When 37 men died on two failed expeditions to the North Pole in the 1880s, it unleashed a torrent of criticism about North Pole expeditions, their motives and methods. Nevertheless, attempts to reach the North Pole increased over the following two decades.

Let’s face it, death imbues value on extreme accomplishment. Many climbers speak of an inner force driving them up the mountain (and I admit, I am not immune to this sort of thing either). But the reality is that there are many motivations for heading above tree line, that mortal danger and “bagging” mountains have a certain social cachet. In scaling K2, which has now once again asserted itself as one of the most dangerous of summits, the climber-who-sees-mountains-as-trophies accomplishes something of greater symbolic heft than an ascent of Everest.

Given this precedent, news of these deaths on K2 won’t deter new climbers but spur them on. Maybe the experienced high-altitude climbers, the Ed Viesturs of the world, will be able to deter the weekend adventurers. But I doubt it.

So here are my depressing predictions: 1) attempts to summit K2 will double by 2010 and 2) these ranks of climbers will have less experience in high-altitude climbing on average than they do now.

I hope I’m wrong.