Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationAnnouncements

Darwin remains remarkably fit for a man who’s been dead 126 years. The UK’s Channel 4 has been airing Richard Dawkins’ three part series “The Genius of Darwin” since 4 August. See screen clips and other bits at the Channel 4 site. Also make sure to check out The Beagle Blog and the Dispersal of Darwin for updates and reactions.

Also on Darwin: Dale Husband rants at length about the attempt to recreate HMS Beagle, update it for science, and sail it around the world. Like Dale, I am skeptical of historical voyage reenactments, something I’ve written about here. Most reenactments, unfortunately, try to prove points about the past by “recreating” them in the present. However, as I see it, Dale is off-base when it comes to the Beagle Project, an enterprise that does not fall into this category of reenactments.

Why? Because the Beagle Project has other fish to fry. When it sails, the new Beagle will offer 1) a consciousness-raising memorial to the work of Darwin, 2) a modern day platform for science, and 3) an opportunity in experiential education, the benefits of which are accepted by schools and universities throughout the world.

Deep Sea News has a big announcement which they reveal, brilliantly, in their first music video. Congratulations Craig, Peter, and Kevin. I want a t-shirt when you guys go on tour.

The University of Delaware is showing an exhibition on Arctic photography called “Poles Apart: Photography, Science, and Polar Exploration.” I’ll be giving a lecture there on 24 September. Information on the event is available here.

The History of Science Society Annual Meeting will be held in Pittsburgh this year from 6-9 November. I’ll be chairing a session called “Vertical Geographies of Science” on Sunday 9 November. Michael Reidy will be talking about Brit scientist and mountain lover John Tyndall, Jeremy Vetter will take on issues in Rocky Mountain ccience, Catherine Nisbett will explain the Harvard College Observatory’s Boyden Expeditions, and Brianna Rego will get to the poisonous bottom of arsenic contamination in mines and groundwater. This excellent team will win us, I’m confident, an HSS playoff berth, and, if Reidy is on his game, a trip to the Series.

But, as conference goers know, Sunday morning sessions are rather deadly. One offers one’s precious research to misalligned chairs and crushed plastic wine glasses. (I think I had four people at my last Sunday morning talk. Two of them were from hotel catering and one was waiting to take back the AV.) So if you are at the HSS, drop by and say hello. I’ll save you a seat.

Columbus on the Green, Part Two

First Encounter: Columbus, Natives, and Lots of Bells

First Encounter: Columbus, Natives, and Lots of Bells

Columbus’s public image has changed many times over the past five hundred years. He was a figure well-known, if not well loved, by Americans in the Colonial Era, a name children memorized in school. The educated Brahman class of the Early Republic even threw him a party of sorts in 1792 to celebrate the three-hundredth anniversary of the discovery of the New World. But as the United States cleaved itself off from Great Britain, the nation sought out new stories that would distinguish it from mother England. In this environment, Columbus gained new popularity. Here was a figure that pre-dated British colonization of the New World, who was not British himself, yet who set the stage for the advancements by Euro-Americans in the centuries to come. This is the analysis of Claudia Bushman, author of the excellent book America Discovers Columbus: How an Italian Explorer Became an American Hero. Only in the late 19th century did Columbus become the superstar that he remains today, hurled aloft by the spectacle of the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1892-3.

Even at the height of popularity, though, Columbus meant different things to different people. White Protestants viewed him as a man who brought Christianity to the New World, whereas Italians and Irish viewed him as the pioneer of Catholicism in America, the herald of their own immigration four hundred years later. Indeed, the years around the Columbian Exposition of 1893 saw the rise of what Bushman calls “Catholic Columbianism” a fierce pride in Catholicism and the American nation. Irish Catholics had tried to develop fraternal organizations around many famous figures and concepts. ( The Ancient Order of Foresters, formed by some Catholic parishioners, confused everyone and was quickly discarded as a title). In 1881, they struck upon the “Knights of Columbus” an organization that was fraternal, Catholic, filled with martial imagery, and avoided hot-button terms like “Irish” and “Italian” which might have put off other ethnic groups. Under this title, Catholic Columbianism flourished, gained broader credibility for its civic work, all the while pushing for increased recognition of Columbus as an “American” hero. By 1909, the K of C (among other groups) had helped establish Columbus Day as a state holiday in 10 states including Connecticut.

Father Michael J. McGivney, Founder of the Knights of Columbus

Father Michael J. McGivney, Founder of the Knights of Columbus

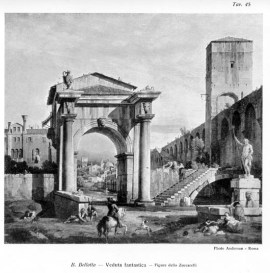

Bushman ends her discussion of Columbus in the early 20th century, showing how broadly popular he had become with many different groups. We fast forward to 1992 when the 500th anniversary of the discovery of the New World provokes a very mixed reaction, particularly from Native Americans. What I find interesting about the Lafayette-Columbus debate in Hartford is that it demonstrates that he remained a contested figure even after all of the pomp and circumstance of the Columbian Exposition and the efforts of the K of C, a flash-point of ethnic controversy. While I haven’t looked at the reception of other Columbus monuments outside of Hartford, I do know that one monument, the Columbus monument in New Haven, CT (headquarters of the K of C, no less), became the meeting ground for Italian Americans protesting the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti.

Columbus Monument, New Haven CT

Columbus Monument, New Haven CT

These early twentieth century protests against Columbus had nothing to do with Native Americans, genocide, slavery etc. They seem to play out between different groups of ethnic Euro-Americans: those who immigrated earlier from Western Europe early vs. those Catholic immigrants who arrived from Ireland and Italy late.

I hope to have more on this story after I do some more digging.

Columbus on the Green

Connecticut State Capitol, Hartford CT

To drive into downtown Hartford is to drive back in time. Shopping malls and 7-11s give way to quiet brownstones, corniced Victorians, and brick factory buildings. Near the city’s center, the gold-domed State Capitol rises above the billboards of I-84. The Capitol is a fairy-tale structure, built in high Gothic Victorian, more at home in a novel by Bram Stoker than in “the Insurance Capital of the World.” Surrounding the Capitol are statues and commemorations of every kind, including Greek goddesses, Civil War cannons, busts of American writers, triumphal arches, and a squat, sword-wielding Confucius. A towering Marquis de Lafayette, mounted upon a stallion, always catches my eye as I drive past the Capitol towards the Hartford Public Library. He is trotting off to help Washington at Valley Forge. I am off to return overdue books.

A bit further down the green, less than a block from the Marquis, stands another figure, an eleven-foot high Christopher Columbus, coppery-green, perched on a nine-foot marble pedestal.

Looking at the statue, one imagines Columbus aboard the Santa Maria (a ship he disliked), clutching a nautical chart, gazing to his right, beyond Hispanola perhaps? But the Admiral needs to watch where he’s sailing. Just beyond the bowsprit, look out, Leviathan-Ho!

:

What were the city fathers thinking? They have set Columbus, discoverer of the New World, on a collision course with the soaring backside of Lafayette’s mount. Perhaps, I thought, Columbus’s remove from Lafayette made this visual insult hard to see. Clearly this had to have been an unintentional joke, the unwitting error of a middle-manager in the Parks Department, invisible to the good people of Hartford, obvious only to prurient-minded people like me. Still a joke is a joke and, seeing as this one involved Columbus, I wanted to know more.

The story of Lafayette and Columbus turns out to be a lot more complicated than I thought. Connecticut has at least seventeen monuments honoring Columbus. While the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893 was the biggest Columbus event ever organized (about 27 million people attended the fair, a number that equaled half the U.S. population), most of Connecticut’s monuments were built, with considerably less fanfare, in the twentieth century. The Chicago Fair, while nominally celebrating Columbus, was really a showcase of White Anglo Saxon Protestant achievement in the New World, a paean to American Exceptionalism.

The Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893. Not an Italian in sight.

By contrast, most of the Columbus monuments of the twentieth-century were built by Italian-American groups. One expects that the new ranks of Italian immigrants pouring into American cities, most of whom were working-class Catholics, did not endear themselves to members of the WASP ruling class. Nor did the Sacco-Vanzetti trial, which led to the execution of two Italian anarchists in 1927, do much to help relations between classes. Or, for that matter, the Italian Mafia, which catered to the thirstier citizens of the Prohibition Era.

Al Capone, Mafia boss, has no statues in Connecticut.

In this climate, one imagines that monuments to Columbus offered the American public a subtle reminder of the greatness of Italian heritage. Tea-totaling Protestants may have held the reins of power in the U.S., but Italian-Americans wanted it made clear: the tower of Anglo-Saxon prosperity rested on the foundations laid by a Catholic, wine drinking sailor from Genoa.

In Hartford, the plan to commemorate Columbus started auspiciously enough. Italian-Americans raised $15,000 to put up their local Columbus on Lafayette Green, then unoccupied by any other statue. Columbus was unveiled on 12 October 1926 before a crowd of three thousand, accompanied by a two-mile parade, floats, and speeches by the mayor of Hartford, the Governor of Connecticut, congressmen, and the Italian vice-council. Prize for “best-looking girl float” (for the float, the girl?) went to the Yolando Club of Waterbury. All in all, it appeared to be a happy event, a win for the Italian community and the civic-minded citizens of Hartford.

This lasted about ten months. Problems began the following year when organizers of the Columbus monument sought to change the name of Lafayette Green to “Columbus Green” in time for the Columbus Day celebration of 1928. The Board of Aldermen, unsure of what to do, referred the issue to the Park Commissioners, who, in turn, referred the issue back to the Board.

Meanwhile, the forces of Lafayette had gathered to launch a counter-attack. The French-American Republican Club drafted a resolution condemning the name change. They were soon joined by a phalanx of societies including the Connecticut Society of the Colonial Dames of America, the Connecticut Historical Society, the Committee on Historic Sites, the Connecticut Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, the French Social Club, the Franco-American Foresters, and L’Association Canado-Americaine, all of whom protested The Great Admiral’s annexation of this small tuft of grass.

Katherine Day, Chairwoman of the Committee on Historic Sites, explained her opposition:

Why intrude Columbus on this area? Or, if so, why not the statues of Leif Ericson, Cabot and all the other brave explorers? … Should not our own soldiers and sailors and civil heroes have first place near the seat of our State life?

Day must have forgotten that Lafayette was a French aristocrat. As Hartford’s ethnic groups squared off against each other, the Board of Alderman quickly tabled the motion to change the name of the green. There matters stood until an Italian-American alderman raised the motion again in 1930.

A plan had been in the works for some time, at least five years, to erect a statue of Lafayette on the Green named after him but it had not moved forward for want of funds. Suddenly, after this second petition to change the name, an anonymous donor offered funds to complete the project. By 1932, Lafayette and his horse had found their new homes on the Green, showing their faces forever to the Capitol, and their backsides eternally to the Mariner of the Seas.

I had assumed that the monumental mooning of Columbus was unintentional. Now I’m not so sure.

Next Post: Columbus on the Green, Part II

The Last Imaginary Place

Two thousand years ago, a new innovative culture emerged in the world, one which established large, wide-ranging settlements and networks of long distance trade. Between 500 and 1500 CE, this culture began to expand, developing new technologies which allowed it to move into other regions thousands of miles from its place of origin. Ultimately, these technological advancements allowed it to dominate and displace the native peoples who lived there. By 1000, it had establishing a place for itself in a new system of trans-Atlantic trade.

I speak not of Romans or Vikings but of the Inuit, who developed from the Old Bering Sea people two thousand years ago on the coast of Alaska. The Old Bering Sea people lived in large, year round settlements and established long-distance trading networks. They developed or acquired the bow and arrow as well as the means to hunt bowhead whales. Shortly thereafter, they began moving northeast, towards the Arctic shores of North America, displacing the Tuniit, an Arctic culture that predated them by hundreds of years. It is not clear what drew the Old Bering Sea people east, but evidence suggests that they were eager to acquire metal impliments brought by Norse peoples who began to occupy Greenland.

All of this information comes from Robert McGhee’s new book “The Last Imaginary Place: A Human History of the Arctic World.” McGhee’s Arctic is no wintery wasteland, but a dynamic place, the crossroads of many different cultures: Asian, American, and European. At 270 pages, McGhee can hardly be comprehensive. But he manages to tell his stories of Arctic history with an impressive cast of characters: Inuit, Tuniit, European, and Siberian.

One of the goals of McGhee’s analysis is to destroy the myths that still haunt our image of the Arctic and its peoples. For centuries, Europeans described the Inuit as the primitive children of nature, a timeless people who scratched out a living in the same manner as their stone-age ancestors did thousands of years before. In truth they had much in common with their European counterparts. They were expansionist, adaptive, and quick to exploit the resources of their environment.

McGhee also manages to link his broader points to personal experience. On the Inuit for example he states:

The realization that the Inuit are not a peripheral people was forced on my mind one night on the coast of Chukotka, as I climbed by myself over the remains of the ancient community at Ekven. A few kilometers up the coast, the low night-time sun was throwing an orange glow on the rocks of Cape Dezhneva, the most easterly point of Asia, and on Great Diomede Island halfway across the Bering Strait to Alaska. In the bright calm night I suddenly had the overwhelming sense that I was not standing at the distant margin of a world, the end of the earth, as far as one could travel from Europe. Instead I was standing at the very heart of another world, a nexus that for millenia had linked the peoples and cultures of Asia and America. It was a world in which many nations and cultures had flourished, among them the Inuit and their way of life.

This is a terrific book. I’ll be writing a more formal review of it soon for The Historian.

Guest Blogger: Russell Potter

I’m very happy to have Russell Potter, author of Arctic Spectacles, give us his views of the current search for missing British explorer Sir John Franklin. Russell’s impressive book Arctic Spectacles: The Frozen North in Visual Culture, 1818-1885 came out last year with the University of Washington Press. He has also recently been profiled by the PBS series NOVA which aired the program Arctic Passage on the Franklin search. If this blog post whets your appetite for more, check out Russell’s website and Google “knol” on Arctic Exploration.