Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationWomen Explorers

At one time returning explorers could expect a hearty welcome back home: good press, medals of honor, product endorsements, and lecture halls filled to capacity. Times have changed. Since the late nineteenth century, the press and public have been tougher on explorers, challenging their missions, their claims of discovery, and their behavior in the field.

Certainly there are still moments when the public’s knees get wobbly: the orbital flights of Yuri Gagarin and John Glenn and Armstrong’s touchdown on the moon. But even national pride cannot quite extinguish the feeling that we are watching some kind of carnival attraction, that things are not what they seem, that the dog-faced boy will reveal himself to be a carny in make-up.

The proof? It’s not just lemon-faced academics who are writing skeptically about travelers and explorers. Critics now come at the subject from all sides. Adventure writers such as Jon Krackauer psychoanalyze the ethos of the “go it alone” explorer in books like Into the Wild while explorers themselves hurl slings and arrows at each other on ExplorersWeb. Reading one of the glibby heroic biographies of Robert Peary or Elisha Kane is a bit like drinking coffee with lots of syrup: too sweet, no bite.

Still there are areas where criticism remains muted or under-reported, where one can read heroic narratives of old and ignore for a while the nattering nabobs of negativism. Mostly I see this in books on women and indigenous explorers.

It’s understandable. For hundreds of years, women and native peoples were routinely written out of explorer narratives. When they managed to make it in, they were usually playing set characters that readers would understand: the women who travel in the footsteps of intrepid husbands, the noble savages and their thievish brethren, all of them children of one sort or another. No surprise that as social mores have changed, we see attempts to bring these two-dimensional characters to life. In the past twenty years, there have been scores of books on women explorers alone. The Boston Public Library’s list of “Adventurous Women: Explorers and Travelers” gives a taste of this literature. Indeed, the fact that the BPL felt compelled to create this list for its patrons says something about popular demand.

Many books on women explorers hew closely to the heroic model of biography that was popular in the nineteenth century. Of her choice of subjects for the book Women of Discovery, author Milbry Polk said:

So in the end, we chose about 84 women that covered 2,000 years of history, more than a dozen different nationalities. And their endeavors crossed a wide swath of interests from every kind of science to our geography and painting. And, honestly, we chose most of them because we really liked them.

I don’t think that there’s anything wrong with an author liking his or her subjects, as long as it doesn’t interfere with reporting the less noble aspects of the subject’s actions. Many women explorers, often white, well-educated, and upper-class, were just as racist and vain-glorious as their male counterparts (Josephine Peary comes to mind here). A number of them did not rail against “sexism,” in our parlance, but accepted the conventional attitude that men and women were inherently different. Indeed, one of the most fascinating aspects of women travelers is the degree to which they were able to turn these conventional attitudes to their own advantage. For example, Americans were transfixed by Nelly Bly’s bid to travel around the world in eighty days . . . not because she aspired to be look or act as tough as the boys but because she seemed so, well, girly.

This does not take away from the impressiveness of her accomplishments or others. Indeed, it makes the story of these women all the more interesting. More often than not, they did not buck a system of rigid gender roles…rather they used the system to make a space for themselves. Certainly this was not the exclusive strategy of women explorers. Frances Willard, Jane Addams, and other women of consequence did the same.

So I think it’s a shame that many biographies play up the idea of heroic women overcoming adversity through sheer strength of will. It’s a simplistic story that doesn’t do them justice. As a result, these books read very much like nineteenth-century biographies of their male counterparts.

Not that all work on women explorers fits into this category. In her account of Mary Kingsley, British explorer of West Africa, Alison Blunt warns of the dangers of placing women travelers on pedestals. Says Blunt:

Recent interest in white women in colonial settings has often taken the form of romantic, nostalgic imagery in literature, television, and film, notably since the 1980s…These approaches isolate and often celebrate individual “heroic” women rather than question constructions of gender… [Travel, Gender, and Imperialism: Mary Kingsley in West Africa, 5-6]

So where do we turn for good work on women and non-white explorers? Here’s a short list of favorites. Patricia Erikson’s current work on Josephine Peary promises a new, nuanced take on this controversial and complicated explorer. Dierdre Stam’s work on Matthew Henson also will provide some balance and context to the U.S.’s most famous African-American explorer. These are works in progress, so in the interim, you might want to read these:

Patricia M.E. Lorcin’s essay on women’s travel writing which offers a good overview of the field as well as some great secondary sources.

Patricia Gilmartin’s excellent essay on women and exploration in the Oxford Companion to World Exploration (which I reviewed here). Also see Gilmartin’s website for a more complete bibliography of her work.

Lisa Bloom’s controversial, pathbreaking book Gender On Ice which discusses the gender construction of Arctic narratives in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Carla Ulloa Inostroza’s excellent blog on the history of women’s travel Mujeres Viajeras

Laura Kay’s course reading list at Barnard.

If all of this gets a bit wonky for you, head over to the Victorian Women Writers Project where you can read the chronicles of Isabella Bird as she travels through the Rocky Mountains and the islands of Hawaii in the 1870s.

Also see my posts AfricaBib on women travelers and the Gertrude Bell Archive

Blue Moon

To see how often speakers at the Democratic National Convention brought up the idea of reaching the Moon, you would have thought they were talking about Florida. Who can forget Ted Kennedy, grand old man of the Democratic Party, telling adoring delegates:

We are Americans. This is what we do. We reach the moon. We scale the heights. I know it. I’ve seen it. I’ve lived it. And we can do it again.

Later, most of these delegates were napping, chatting, and or freshening up their martinis when Brian Schweitzer told the floor:

President Kennedy’s idealism and spirit of possibility inspired [my parents] to send all six of us children to college. And when he said, “we’re going to the moon,” he showed us that no challenge was insurmountable.

No problem taking a martini break at the DNC or RNC, however, because one can always hear the same speech again. So it was with Ted Sorensen’s speech a few hours later:

Confronting a Soviet military advantage in space, [Kennedy] made all Americans proud by literally reaching for the moon.

Or if they stayed in the bar all afternoon, they could still reemerge on the DNC floor to hear Frederico Pena say:

John Kennedy, a Democratic president, committed us to putting a man on the moon. American energy, American technology, American jobs, ready to be created, right now. That’s the change we need.

Even if they passed out in their hotel rooms, they could still pick up a copy of the DNC’s Platform Report “Renewing America’s Promise” which would have told them:

We know that at every turning point in our nation’s history, we have demonstrated our love of country by uniting to overcome our challenges-whether ending slavery, fighting two world wars for the cause of freedom or sending a man to the moon.

In all of this, the moon has no value in and of itself. It does not represents an economic or scientific imperative. Rather, it functions solely as a benchmark of American accomplishment, a symbol of technological progress, and a reminder that young, good-looking Democratic presidents have the chutzpah to do cool things in office.

No surprise then that Barack Obama’s statement on Science Policy also mentions the moon, albeit with a slightly different spin:

In the past, government funding for scientific research has yielded innovations that have improved the landscape of American life-technologies like the Internet, digital photography, bar codes, Global Positioning System technology, laser surgery, and chemotherapy. At one time, educational competition with the Soviets fostered the creativity that put a man on the moon. Today, we face a new set of challenges, including energy security, HIV/AIDS, and climate change.

In this incarnation, reaching the moon represents a benchmark of American educational accomplishment, a golden age that Obama implies is beyond us now. Indeed, Obama’s Space Policy in late 2007 seemed to pit money for space exploration up against federal money for education. Said Obama:

We’re not going to have the engineers and the scientists to continue space exploration if we don’t have kids who are able to read, write and compute.

As for Republicans, the moon received nary a mention at their national convention. Testament to the fact, I imagine that they see it primarily as free advertising for Kennedy and therefore Obama by proxy.

On the surface John McCain’s policy on space exploration seems much more vigorous than Obama’s. He is committed to continuing President Bush’s 2004 Vision for Space Exploration (VSE) which anticipates a return to the moon in the coming decade as a prelude to the eventual manned mission to Mars in 2020. Yet what is the ultimate objective of human space flight? McCain begins by discussing (much as Kennedy did) the accomplishments of international rivals:

China, Russia, India, Japan and Europe are all active players in space exploration. Both Japan and China launched robotic lunar orbiters in 2007. India is planning to launch a lunar orbiter later this year. The European Space Agency (ESA) is looking into a moon-lander, but is more focused on Mars. China also is actively pursuing a manned space program and, in 2003, became only the third country after the USSR and the US to demonstrate the capability to send man to space. China is developing plans for a manned lunar mission in the next decade and the establishment of a lunar base after 2020.

Ultimately, McCain concedes that the principle objective of human space flight is not science or commerce but national prestige. Boldly going where no one has gone before is, in effect, a matter of keeping up with the Jones:

Although the general view in the research community is that human exploration is not an efficient way to increase scientific discoveries given the expense and logistical limitations, the role of manned space flight goes well beyond the issue of scientific discovery and is reflection of national power and pride.

This is a very expensive way to show “prestige.” So despite the Democrats paper-thin, hokey moon-talk at the DNC, and the lack of Obama’s specifics about alternatives to human space exploration as proposed by the VSE, I tilt towards Obama on space policy if only because McCain seems to be willing to maintain the rather shallow vision of exploration put forth by Bush.

The Armchair Voyager

Autumn, the season of waiting. Everest climbers stow away their ropes and crampons. The polar explorer watches the sun disappear and settles in for the encroaching winter. Expedition wonks like me shelve their boxes of research to tend to their courses and panicky undergraduates. These are the Ides of September, a time of imagining other places we’d rather be.

Time to work on the winter reading list.

On mine: Mary Terrall’s The Man Who Flattened the Earth: Maupertuis and the Sciences in the Enlightenment, James Delbourgo and Nicholas Dew’s Science and Empire in the Atlantic World, Gary Kroll’s America’s Ocean Wilderness: A Cultural History of Twentieth Century Exploration, and J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. Probably something related to K2 as well if I can find it.

For those looking for the raw material of voyaging, untouched by the meddling hands of historians, try American Journeys, an online collection of 18,000 pages of travel narratives from the Vikings of 1000 to the Western Surveys of the 19th century. Read the voyage of Eric the Red, Columbus’s discussion of cannibals and Amazons, or La Perouse’s doomed voyage around the world.

Or see Early Canadiana Online, an archive of almost 40,000 documents chronicling Canadian history, including travel narratives of the Far North. (The history of the Hudson Bay Company alone accounts for 20,000 pages). Much of this should be read with an open tin of pemmican.

Finally, one has to pay a visit to the American Memory project of the Library of Congress, which includes narratives of early Western exploration, maritime voyages, prairie settlement, Rocky Mountain migration, photos of the Great Plains, and documents on Lewis and Clark among others.

Are there online travel archives that I’ve missed? Book favorites? What will you be reading during the winter gloaming? Let me know.

Web Review: ExplorersWeb

There is a freedom that comes with studying dead people. We, the historians of the not-so-recent, learn about our subjects in archives and newspaper columns, from photos, maps, and bank statements. We reveal what we’ve learned, personal and perhaps unflattering, knowing that the people we’ve researched cannot talk back to us, sue us, or toss rocks through our windows. (This is work best left to other historians). Still there are times when I meet my subjects sort of. I often talk shop with modern-day explorers at meeting and lectures, some of whom share the goals and sensibilities of the people I study. This is always a welcome experience for me, but one that often feels a bit strange, since I look at the work of past explorers with such a critical eye. What has been refreshing to find, however, is how self-aware and historically-minded many modern day travelers and explorers are.

For example, take the site ExplorersWeb.com, a clearinghouse of information about extreme travel in the polar regions, the oceans, mountains, and space. It is the brainchild of Tom and Tina Sjogren, two Swedish uber-travelers, who provide daily updates about expeditions in the field as well as their own exposes of expeditionary bad-behavior, from selfish guides, and faulty equipment manufacturers, to climbers who fib about their summit climbs. The reports of Explorersweb have not been without controversy, particularly from veteran mountaineers who’ve been the object of scrutiny. Nevertheless, it’s worth taking a look at.

Book Review: Trying Leviathan

D. Graham Burnett. Trying Leviathan. the Nineteenth-Century New York Court Case That Put the Whale on Trial and Challenged the Order of Nature. xiv + 304 pp., figs. biblio., index. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007. $29.95 (cloth).

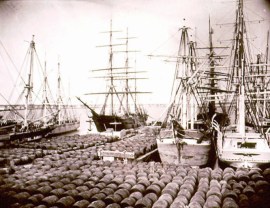

On 1 July 1818, Samuel Judd landed on the wrong side of the law. He purchased three casks of uninspected whale oil from John Russell, violating a New York statute that required all fish oil to be inspected before sale. When James Maurice, fish oil inspector, learned of the sale, he took Judd to court. Thus began Maurice v. Judd, a three-day trial that unfolded in the Mayor’s Court in mid-winter 1818.

Fish oil, let’s be honest, doesn’t fire the imagination, and Maurice v. Judd will never carry the gravitas of other iconic American trials such as Brown v. Board or Roe v. Wade. But as Trying Leviathan shows, the case has a number of hidden gems, each carefully quarried by D. Graham Burnett. Had Judd denied buying the casks, or alternatively, agreed to pay the $75 dollar fine, things would have turned out differently. As it was, he took a novel approach to his defense, arguing that the law had been misapplied; the casks in question did not contain fish oil, but whale oil. By framing his case in this way, Judd transformed what would have been a quotidian commercial dispute to a public debate over modern taxonomy, namely: “Is the whale a fish?”

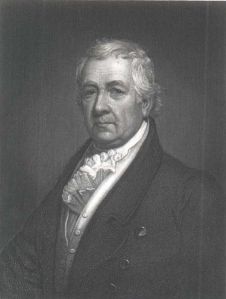

Judd’s clever defense allows Burnett to use Maurice v. Judd as a perch from which to view the taxonomic landscape of early 19th century America. Ranging over this landscape was Dr. Samuel Mitchill, physician, commissioner, assemblyman, and congressman, who entered the courtroom prepared to defend the status of whales as mammals. Mitchill was every lawyer’s dream of an expert witness: well-known (see above) and well-respected, especially as a lecturer in natural history at the College of Physicians and Surgeons. But Mitchill’s day in court did not go smoothly, and he was forced to acknowledge serious disputes among philosophers over taxonomic classification. Maurice’s attorneys picked off Mitchill’s arguments, but didn’t stop there, taking aim at Mitchill himself as well as what he represented: gentleman-philosophers who had lost touch with common sense. As Burnett tells it, the drubbing of Mitchell signaled a broader standoff between the public and its men of science. Maurice’s lawyers “went after the cultural authority of the sciences in general and natural history in particular.” (75) No longer was this a case about casks of oil, he claims, but “the proper place of science and men of science in the Republic…”(75).

Yes, well, this hurls the argument a bit further than the sling permits. It’s hard not to love trials because they provide the spark of controversy so useful in historical analysis. Whether these sparks represent the brushfires of a broader culture, however, remains to be seen; the artificial, polemical nature of the American court, much like American politics, sometimes draws lines where, say, smudges are more appropriate. Indeed, a key contribution of Trying Leviathan is in showing that Maurice v. Judd cannot be reduced to the binary opposition of Men of Science v. Everyone Else. Burnett is at his best in showing that the whale, common to Americans of many stripes, was not, in fact, common at all. Men of science, the general public, whalers, and commercial men all understood Leviathan differently, gathering their knowledge of it in different ways. The writings of Linneaus and Georges Cuvier may have inspired a generation of taxonomists to cast the Whale out of Fishes, but ordinary Americans still hewed closely to a Biblical taxonomy that classified animals into flyers, crawlers, and swimmers. Whalemen, on the other hand, were experts in a “superficial natural history” (125) of their prey, a phrase Burnett uses literally, rather than pejoratively, to mean a knowledge of the outer parts. They, more than anyone else, could identify whales at a distance from blow pattern, fin shape, fluke, or splash. Their knowledge extended to the outer layers of the whale, from black skin to the thick blanket of fat that they collected for the tryworks. What lay beneath this blanket, however, remained mysterious. The meaty parts of the whale were not valuable, and the animal, once disrobed of its blubbery coat, soon sank to the bottom. But this was exactly the part of the whale that Mitchill and other taxonomists (inspired by the excavating impulse of Cuvier) found so interesting.

Historians of science may feel satisfied at this point, having seen views of the whale from the street, the wharf, and the lecture hall. But Burnett is not quite done, taking the reader into the marketplace, too, where vendors and purveyors understood this creature in their own peculiar way. Commercial men attended themselves to the specific qualities of whale oil, a commodity that, whatever rung the whale occupied in God’s Ladder of Creation, was not fish oil. Whale oil, a clean substance with few impurities, was rendered by trying blubber in pots aboard ship. Fish oil, on the other hand, was nasty, impure stuff, a stinking emulsion of oil, blood, scum, and other fishy matter used primarily in tanning. This commercial taxonomy of the whale might seem a rather narrow, arcane bit of information to end on, but Burnett is right to pursue it; the commercial distinction between whale and fish proved crucial in determining Maurice v. Judd (for the plaintiff) and brought about subsequent changes in New York law (for the defendant).

Burnett’s only misstep in Trying Leviathan is overstating Maurice v. Judd’s relevance to a series of historiographic debates. The book concludes, rather deliriously: “Is the whale a fish? Is science social? Is philosophy historical? The precedent question is always this: What stories must be forgotten to answer these questions?” These are good, if stratospheric questions, but ones that Burnett’s analysis of Maurice v. Judd cannot answer and that divert the reader from his greatest accomplishment: the creation of a new map of the whale in American culture, one textured by close-readings and breadth of scale, engraved with love and a sense of wit.

Thanks to the University of Chicago Press for permission to publish this review. It will appear in an upcoming issue of Isis.