Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationLess is More

No one can predict what next year’s federal budget will hold in store for NASA. A medium-term recession will put pressure on Congress and the next president to make cuts in the space program. Neither John McCain nor Barak Obama have spent any political capital embracing President Bush’s Vision for Space Exploration, though McCain’s on the record as supporting it. Obama has made sounds about delaying it, diverting funds into science and engineering education. Whether there is any money left to divert, cuts at NASA are now a likely scenario. After all, it’s hard to imagine a trillion-dollar program for space exploration holding up during a prolonged economic downturn. Meanwhile, reports from the Ares rocket research and development program have not been promising. The shuttle fleet is scheduled to go into retirement by 2010 and American astronauts will become dependent upon third parties to get them into space.

But perhaps there is something positive to be gleaned in all of this bad news. As the Mars rovers and Phoenix lander have proven, unmanned exploration is comparatively cheap. Moreover it has been productive to space science. Relying upon the Russians Soyuz to shuttle Americans to the International Space Station may not be in the best interests of the United States long-term, but it has paid off in other ways already. As John Schwartz wrote in the New York Times last week:

Those who work side by side with their Russian counterparts say that strong relationships and mutual respect have resulted from the many years of collaboration. And they say that whatever the broader geopolitical concerns about relying on Russia for space transportation during the five years when the United States cannot get to the space station on its own rockets, they believe that the multinational partnership that built the station will hold.

Among many free-market thinkers, economic downturns are useful insofar as they eliminate, albeit painfully, failing or inefficient businesses and modes of production. If this is a viable model for business, might not it also hold true for the U.S. space program? Forced to downsize and become more efficient, NASA would turn its attention to those lower cost projects that had been secondary priorities during the boom years. Perhaps with all of this talk of international space collaboration, depleted budgets will finally provide the incentive for long-term collaboration. I do not know enough about economics or NASA politics to know if this will happen, but it’s good to have sunny moments when the forecast is calling for so much rain.

Digital Archive: James Cook

In his book New Lands, New Men, William Goetzmann describes the 18th and 19th centuries as the “Second Age of Discovery.” The First Age of Discovery, kicked off by the Mediterranean powers of the 15th century, developed maritime routes to Africa, Asia and the Americas. Best known of these early discoverers is Christopher Columbus who sought to extend Spanish dominion, proselytize natives, and bring home piles of loot, objectives followed by his 16th and 17th century successors.

By the 18th century, however, the goals of exploration had changed. Empire and commerce still had their place in voyages of discovery, but they increasingly made room for other, secular objectives such as natural history, ethnography, and natural philosophy, changes that reflected new attitudes about knowledge and learning back home in Europe.

Captain James Cook, who led three expeditions to the Pacific in the 1760s and 1770s, became the poster-child of Enlightenment voyaging. Of modest birth and education, Cook was not himself a philosopher of nature. But his command of three discovery expeditions – to study the transit of Venus, discover the extent of the Antarctic continent, and investigate the possibility of a Northwest Passage – set the benchmark for scientific expeditions to come over the next century. Cook’s chronicles and those of his men of science (Joseph Banks and Johann Forster) provided models for the expeditions of Jean-Francois de la Perouse (France), Alessandro Malaspina (Spain), and Charles Wilkes (United States) among others.

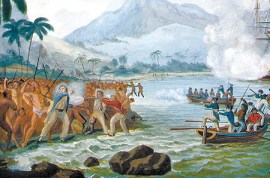

Cook’s serendipitous discovery of the Hawaiian Islands in 1778 (which he named the Sandwich Islands) was also, ultimately, the cause of his demise. After a series of quarrels with Hawaiians of the Big Island, Cook was killed in a skirmish with islanders on the beach of Kealakekua Bay.

The National Library of Australia and the Center for Cross-Cultural Research have developed an impressive website on Cook’s legacy, South Seas: Voyaging and Cross-Cultural Encounters in the Pacific. Focusing on Cook’s first voyage, South Seas offers accounts from Cook, Joseph Banks, Sydney Parkinson, and John Hawkesworth. A world map of Cook’s route allows the viewer to zoom in features of interest, identifying the dates of Cook’s passage, landfalls, as well as diary entries for dates mentioned. A set of four “Cultural Atlases” offer maps and descriptions of the native peoples which Cook visited in Tierra Del Fuego, the Society Islands, Botany Bay, and Endeavour River. South Seas also offers some indigenous histories and European reactions to Cook’s voyage.

There are a few “links to nowhere” on South Seas. Perhaps the project ran out of funding before it was fully completed. But even in its unfinished form, there are gems here for the student of Enlightenment voyaging.

Also on Cook see:

The Mariner Museum’s Age of Exploration

The Historical Record of New South Wales on Google Books

Many of the full text books on South Seas are also available on Google Books for viewing or download

The Secular Mountain

In 1336, Italian poet Francesco Petrarcha climbed Mount Ventoux in southern France. Mt Ventoux is not very challenging as summits go and Petrarch, as he would later be known, had plenty of help. He traveled with his brother Gherardo, servants, and I would imagine, a light-bodied Chianti. But what stands out about his ascent, or more precisely his writing about his ascent, is the fact that he climbed Mt Ventoux for no practical purpose at all. Petrarch climbed Ventoux because he wanted to “see what so great an elevation had to offer.”

Scholars have their doubts about whether Petrarch made it anywhere near Ventoux. This is beside the point. His writings about his ascent, whether real or fiction, express a new attitude towards travel, mountains, and the process of enlightenment. After a long day, Petrarch tells us that his party reached the summit of Ventoux where he looked down upon the clouds, the distant Alps, and “stood like one dazed.” For Renaissance scholars, the ascent of Mt. Ventoux represented a critical moment in the development of humanism, a desire to access truths about the world through secular experience, rather than rely upon prayer, church teachings, or the reading of Scripture. In Petrarch’s “seeing what the mountain had to offer” the modern ear hears an echo of George Mallory’s 1923 statement to the New York Times explaining that he wanted to climb Everest “Because its there.”

This secular vision of the mountain – a place for human achievement and perhaps self-enlightenment- is a modern thing as historical processes go. For most of recorded history, mountains were landscapes for the supernatural. Roman, Celtic, and Hindu cultures (among others) placed their gods in the mountains. I was struck, as I read Isserman and Weaver’s Fallen Giants this week, that the first Western descriptions of the Himalaya were not from climbers but from Christian missionaries who trekked through Nepal and China.

But I think we read too much into the secular nature of Petrarch’s ascent. After enjoying the view for a few minutes, Petrarch tells us that he pulled out his copy of St Augustine’s Confessions (not the secularist’s obvious choice for mountain literature) where it opened, miraculously, to a passage about mountains:

Now it chanced that the tenth book presented itself. My brother, waiting to hear something of St. Augustine’s from my lips, stood attentively by. I call him, and God too, to witness that where I first fixed my eyes it was written: “And men go about to wonder at the heights of the mountains, and the mighty waves of the sea, and the wide sweep of rivers, and the circuit of the ocean, and the revolution of the stars, but themselves they consider not.” I was abashed, and, asking my brother (who was anxious to hear more), not to annoy me, I closed the book, angry with myself that I should still be admiring earthly things who might long ago have learned from even the pagan philosophers that nothing is wonderful but the soul, which, when great itself, finds nothing great outside itself. Then, in truth, I was satisfied that I had seen enough of the mountain; I turned my inward eye upon myself, and from that time not a syllable fell from my lips until we reached the bottom again.

As I see it, the lesson Petrarch gleans from his mountain experience is the opposite of Romantic or modern notions about climbing: he tells us that one cannot find truth on the mountain through exertion and sublime experience. Indeed such spectacular landscapes present dangers to the pilgrim seeking real enlightenment. The true path, Petrarch tells us, is an inward path, one without the distractions offered by the wonders of the natural world.

It seems now that the world’s highest mountains have been shorn of their status as places of secular enlightenment and are now merely secular. Richard Salisbury and Elizabeth Hawley’s stunning piece of statistical work on Himalayan climbing makes clear that the 8000 meter peaks of South Asia are sought after more than ever before. Yet increasingly only a few peaks (Ama Dablam, Cho Ayu, and Everest) see increased traffic, mostly by commercial climbing companies which outfit expeditions for high-paying clients, a conveyor belt of climbers who don’t seem much interested in the process of climbing, the view, or anything much else except for the summit. Meanwhile, the other peaks of the Himalayas see fewer and fewer climbers, even “sacred” mountains such as Kangchenjunga. What thoughts goes through the hypoxic climber’s mind when he gets to Mallory’s “there” ? Does he see a vision of God? A warning from Augustine? Or only a picture for his blog site?

Read Petrarch’s Ascent of Mount Ventoux

Look at Salisbury and Hawley’s Himalayan Database

Mission to Mercury

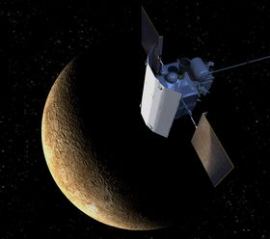

Regard fleet-footed Mercury, Roman god of travel and trade, the one-man postal service of Mt Olympus. It’s ironic that he has come to represent the solar system’s densest planet, an object consisting of 70% nickel and iron. Still Mercury is quick, speeding around the sun at a rate of 47 km/second, faster than any other planet.

This week Mercury Messenger will pay a visit to this world of metal. Messenger lifted off on 3 August 2004 in hopes of, among other things, figuring out why Mercury is as dense as it is. It will also measure the planet’s geology, magnetic field, atmosphere, and core composition. After a brief fly-by this week, Messenger will prepare for its final insertion into Mercury’s orbit in 2011.

Messenger’s price tag comes in at $446 million, a steep price when compared to other terrestrial transport vehicles of the same name. One Mercury Messenger would buy 15,379 Mercury Sables, fully loaded with satellite radio and heated front seats. But Messenger is actually rather cheap when placed up against the leviathan craft of the Constellation Program developed for travel to the Moon and Mars. At slightly under half a billion dollars, Messenger works out to $1.50 for each U.S. resident, about the same cost per person (accounting for inflation) as Mariner 10 in the 1974. Indeed, this seems a reasonable price for a planet that has only received one visit in 35 years.

Happy travels Messenger.

See more here at the NASA Messenger Website

The Dust-Free Blog

Posts seem tidy things when they see the light of day, capped by neat titles, tucked into single columns. But bloggers everywhere share a dirty secret: this sort of writing is a messy business, profligate in its use of words and images, throwing off bits and scraps faster than the butcher’s apprentice. Seventy posts have left me with all sorts of unfinished business: links that never make it to the right hand column, half-written posts that remain unpublished, category listings that do not get updated. So I have done some housecleaning today. Mostly you can see the work on column to the far right. There is a new category of links: Online Archives which have primary source materials on travel and exploration. There are a number of Library of Congress collections here, some travel writings by Isabella Bird, the NOAA archive on 19th century oceanography books, and some visual archives including David Rumsey’s online map collection and the JPL’s NASA image archive. The “Complete List of Posts” has been updated through yesterday and I’ve added some links to my online research and talks on the “About” page.