Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationThank You FHSA

This morning the Forum for the History of Science in America presented me with their 2008 Book Prize for my book The Coldest Crucible. Officer Paul Lucier presented the prize:

On behalf of the membership and officers of the Forum for the History of Science in America, it is my pleasure to announce that the 2008 Forum Prize Committee has unanimously agreed to award this year’s book prize to Michael F. Robinson for The Coldest Crucible: Arctic Exploration and American Culture, published in 2006 by the University of Chicago….this is a history of science of a very different sort. Instead of focusing on how the explorers collected specimens or tried to map the icy unknown, Robinson explains, in very clear and refreshingly concise fashion, how the Arctic and its explorers tried to collect sponsors and funding, and how they tried to present themselves and their expeditions as relevant to a large public.

My last time in Pittsburgh was in 1998, also at a History of Science meeting. It was the occasion of my first academic paper. I read it, hunched over a podium, to four elderly men in varying states of consciousness. I was tense, the paper was dry, but I don’t think anyone was awake enough to notice. The paper made me wonder why I spent so much time working on these subjects when no one was ever going to read or care about them.

It feels particularly good, then, to receive this award in Pittsburgh (at the same hotel no less). Thank you FHSA! Thanks too to for the generous write-ups in the Hartford Courant and the University of Hartford’s UNotes Daily.

Voyage to Pittsburgh

Tomorrow I leave for the History of Science Society Annual Meeting in Pittsburgh. I thought I would save a few bucks by driving, since Connecticut is practically neighbors with Pennsylvania (apart from a small wedge of New York). But I didn’t factor in that Pittsburgh is at the western extreme of the state, closer to West Wheeling, West Virginia than Hartford CT, an embarrassing oversight for someone who claims to know something about U.S. geography and exploration. So I will pay for my mistake by sixteen and a half hours of donuts and talk radio. I’m bringing my camera to chronicle the journey. I will try to post while I’m in the field (or at the conference) so until then, happy travels.

Routes Up the Mountain

Two weeks ago I wrote a post criticizing the modern commercial ethos of Himalayan climbing. As I continue to dig deeper into the history of Himalayan climbing (guided by the excellent book Fallen Giants), I am beginning to realize what diverse motives brought western climbers into the Himalayas and Karakorum. Nineteenth century climbers, like Arctic explorers, saw climbing in romantic and nationalistic terms, but they also viewed it in other ways as well.

The story of Sir Francis Younghusband, British Army officer, shows the importance of empire in the exploration of these regions. In addition to adding to the West’s geographical knowledge of these distant ranges, Younghusband spent his days outmanovering the Russians and trying to occupy Tibet. Yet Younghusband was, as modern climbers go, rather atypical. He did not seek to summit peaks as much as to survey and move through ranges. As much as he was an agent of empire, he was also deeply affected by the mystical traditions of India and Tibet.

So too was Aleister Crowley, whose role in the failed K2 expedition of 1902 has been eclipsed by his reputation as “The Great Beast 666,” and “The Wickedest Man in the World.” Crowley’s love of mountains was life-long and also an opportunity for spiritual reflection.

Alfred Mummery, on the other hand, saw mountains as the testing grounds for technical climbing and technological advancement. Mummery, inventor of the Mummery tent, first attempted to climb Nanga Parbat in 1895 and died in the attempt. It seems that Mummery viewed mountains tactically, rather than strategically, and thus, as Steward Weaver tells it, failed to see the Himalayas in their proper scale. For Mummery, the Himalayas were an overgrown version of the Alps.

Still others, such as Alexander Kellas, were “traversers” climbing up one side of the mountain and down the other – an enormously difficult and dangerous thing to do on 8000 meter peaks. Kellas spent his time on the mountain trying to figure out the physiology of altitude sickness, leading to new ideas about mountain acclimatization. One wonders what Kellas would have observed from the Royal Geographical Society’s Everest expeditions in the early 1920s. He died before reaching Everest base camp in 1921.

Readers who find these stories interesting should check out Bill Buxton’s excellent online mountain bibliography.

A Blog of One’s Own

I have tried to avoid the question “why blog?” here at Time to Eat the Dogs. It’s not a bad question. But it’s one that academic bloggers seem to be drawn to like seals to herring. Most non-academic bloggers do not feel so compelled. Why the obsessive interest?

The kind answer: academic bloggers, particularly those in the humanities and social sciences, spend much of their time in the Academy scrutinizing the mysterious ways of human culture. As blogs become part of culture, it’s almost instinctive for the academic to ask “why are we doing this?”

Less kind: self-interest, or more accurately self-protection, compels academics to explain their bloggish ways. As much as the Academy is a place of learning and critical debate, it is also a place steeped (some might say stratified) in tradition. Nowhere is this more true that in writing and publishing. From their first days as graduate students, academics are trained to understand the intricacies of publishing: the hierarchy of peer-review journals, the differences between academic and trade presses, the proper format of query letters, the dilemmas of annotated footnoting. Blogs have no place (yet) in this universe of words.

Indeed, in the great publishing chain-of-being, blogs rank near the bottom, somewhere between Mad Magazine and the Hallmark card. Not that blogs inspire anger or animosity. After all, why get worked up over something that doesn’t matter? No, for the unblogged academic majority, I suspect, the “web log” connotes something trendy, frivolous, and self-absorbed (and indeed, these connotations sometimes apply). When I mention to colleagues that “I blog,” I am met with patient smiles, as if I said “I cross-dress.” Nothing illegal or suspect, just a too little outré.

In short, I think academic bloggers answer the question “Why blog?” more for the benefit of their disbelieving academic colleagues than the general public. This is why authors asking “Why I blog?” sound as if they are answering the question “Why am I a Bolshevik?”

So what inspires me to wade into this issue now, after having avoided it for six months? I just read two excellent discussions of the “why blog” question from fellow historians of science Ben Cohen and Will Thomas. Both pieces take the question to new, interesting places.

In “Why Blog the History of Science?” Cohen maintains that academics find many motives to blog, but that they ultimately fall somewhere on an axis with broad communication on one end and novel contribution on the other:

Those who write a Web-log (“blog”) find themselves somewhere along that axis, either with the belief that they are generating and/or influencing public conversation or with the motivation to explore a given subject in depth.

Cohen concludes that his own motives are not fixed, that he slides back and forth along the axis depending on the topic and intended audience. As such, Cohen blogs with a number of different goals in mind: pedegogical, civic, and intellectual.

In Blogging as Scholarship Thomas uses Cohen’s piece as the starting point to further examine “the insider blog” which Thomas sees as a “laboratory of scholarship.” Over the centuries, universities have developed a number of ways for scholars to communicate with each other (via journals, seminars, and conferences) which do not require logging into WordPress or Blogger. But Thomas points out some of the ways that blogs extend or amplify the useful functions of scholarly communication (which he identifies as articulation, speculation, recovery, and criticism).

Time to Eat the Dogs probably rests somewhere between Cohen’s cabinet of curiosity blog The World’s Fair and Thomas’s more inside-baseball blog Ether Wave Propaganda.

Cohen and Thomas nicely cover the spectrum of academic blogs as tools of public and professional communication. Yet there is also a personal dimension to academic blogging, one that keeps me posting even when the other objectives seem abstract or distant.

1. The Blog as Writers’ Workshop. I credit graduate school with honing my critical faculties as a scholar, teaching me a great deal about historical subjects, and giving me various methods for studying them. I also credit it with distorting my voice as a writer. Not to blame it all on graduate school. In truth, my professors valued good writing and pushed me to deliver solid, jargon-free prose. Yet even this wasn’t enough to keep me from becoming assimilated into the collective, Borg-ian voice of the discipline, a voice that academics integrate into their own writings almost unconsciously.

Blog writing, even within the disciplines, seems to follows looser conventions. Some of this, perhaps, comes from the expectation that blogs are supposed to be more free-wheeling. I think it also comes from the pacing of blog writing. I try to write about three posts a week. This has made it easier to keep limber as a writer, especially during the semester when the demands of teaching shut down bigger projects. It also makes it difficult to over-write (as was often my problem in graduate school). My blog has forced me to write faster, to speak more plainly, and to get to the point more quickly.

2. A Blog of One’s Own. Virginia Woolfe lamented the restrictions placed upon women writers, restrictions which kept them away from the writer’s table to attend the demands of spouse and family. We live in a different world than Woolfe’s, yet the dilemma of writing vs. family remain. I wrote most of my dissertation without kids. I have three kids now and it seems impossible to think of my next book unfolding in the same way as my first one. There will be no more obsessive twelve hour days in the archives, no six-month writing fellowships far from home. But blog writing takes place in the corners of the over-stuffed life, an hour at lunch or in the late evening. These scraps of time always feel insufficient to take on the leviathan book projects that sit on my shelf, but they are enough to write 300 words about an item of interest.

3. The Great Uncoiling. As the items of interest pile up, I feel like my work is taking on a breadth that I have long sacrificed for depth. I entered graduate school with a surfeit of interests. But after taking a master’s degree, I began the long, slow spiraling-in on the subject that would become my thesis, the monograph that would eventually make me an expert in the narrow and the arcane. Blogging has offered me a way of unwinding the process, of venturing outward, testing the ground, roaming somewhere else, and testing it again. Since I’ve started blogging, I’ve taken on issues that fall outside of my areas of expertise. In a sense, it feels like I am returning to 1995 and 1996, years when I read far, wide, and ecumenically as a masters student. Even then, I thought of this peripatetic reading as the means to an end rather than an end in and of itself. Still the journey was thrilling and, in retrospect, necessary. So here I am again, spiraling out, with blog as muse, dilettante, co-pilot.

Darwin in Four Minutes

Charles Robert Darwin (1809-1882), expert in barnacle taxonomy, lived his life as an omnivorous reader, letter-writer, and pack-rat. He attended college and traveled abroad, married his cousin Emma, and settled at Down House. There he wrote books, doted on his many children, and suffered bouts of chronic dyspepsia.

We don’t remember Darwin much for these details, eclipsed as they are by his work on evolution. But they are worth noticing if only to make a simple point. Darwin did not live life in anticipation of becoming the father of modern evolutionary biology, a status that seems almost inevitable when we read about Darwin’s life now. Despite the distance of time and culture which separates us from Darwin, he went about his business much as we do: working too much, getting sick and getting better, fretting about others’ opinions, and seeking solace among his friends and family.

In spite of the scrutiny paid to evolution, or perhaps because of it, we continue to see Darwin through a glass darkly, distorted by a body of literature that, despite sophisticated analysis and a Homeric attention to details, reduces his life to the prelude and post-script of the modern era’s most important scientific theory. This is not to beat up on the “Darwin Industry” which has produced a number of superbly researched, balanced portraits of Darwin. But the nuance of such works cannot overcome the weight of Darwin as a mythic figure in the popular imagination.

So what should we remember about Darwin?

He was not the “father” of evolution. The idea that species could change over time had a long history that predates Darwin. “Transformism,” as evolution was called, had many adherents including French naturalists Comte de Buffon and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck. Even Darwin’s grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, took up the cause, defending the idea in his book Zoonomia (1794-96). But by the mid 19th century, transformism carried with it the whiff of quack science and radicalism. For the empirically-minded European naturalist, accepting transmutation of species was akin to believing in Sasquatch, an idea made all the more unpalatable because it brought with it an uncomfortable proximity to lower social classes and leftist political causes.

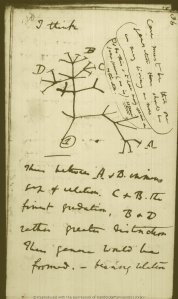

Darwin’s reputation rested on different grounds. He did not become the buzz of London because he supported transformism. Rather, he brought to the defense of transformism a stunning, almost overwhelming, body of evidence. In Origin of Species, published in 1859, Darwin gathered his data from a number of different fields: comparative anatomy, taxonomy, biogeography, geology, and embryology. Darwin had come to the idea of evolution relatively early in his scientific career. A sketch of an evolutionary tree appears in Darwin’s notebook in 1837. But Darwin kept his views close to his chest, amassing arguments and pieces of evidence over the next twenty years.

But this wasn’t the only reason why Darwin’s monograph flew off bookshelves faster than The Da Vinci Code. Origin of Species posited an entirely novel mechanism of evolution, natural selection, which explained why species change over time. According to Darwin, all populations quickly outgrow the ability of their environments to sustain them. Ultimately individuals of a species are forced to compete with one other for limited resources, winnowing the ranks of survivors to those who are best adapted to the conditions around them. These survivors pass on their successful traits to their offspring and change the constitution of the population accordingly.

Sounds tidy enough, but natural selection had to compete with a number of other possible mechanisms for evolution. For Buffon, species “degenerated” over time, moving away from their original form. For Lamarck, species changed when individual organisms become modified during their lifetimes and passed down these modifications to their offspring (also known as the inheritance of acquired characteristics). For others, evolution showed the handiwork of the Creator who nudged species, humans in particular, up the ladder of perfection.

In today’s world of creationist parks, polarized school boards, and dueling fish decals, the battle line has been drawn over the idea of evolution. Do species change over time? This is the question that sends evolutionists and biblical literalists charging down the hill at each other like the kilt-clad armies of Mel Gibson. But this was not always the case. In Darwin’s day, evolution had broad (though not universal) support from naturalists as well as liberal members of the clergy.

It was not evolution but natural selection which ruffled feathers. For many nineteenth-century Britons, natural selection seemed Deist at best and nihilist at worst. After all, what room did Darwin allow for God if nature was doing all of the selecting? As a result, many chose to believe in a theistic or “teleological” version of evolution which accepted Darwin’s evidence for evolution but rejected the mechanism he thought lay behind it.

To be fair, even Darwin had his doubts about whether natural selection could explain all aspects of species change. Later editions of Origin of Species left the door open to other mechanisms of evolution, particularly the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Only in the early twentieth century did natural selection finally win the day among professional scientists.

All of this had led some modern critics of Darwin to point out that his work falls short of certainty, that gaps in the evidence, particularly in the existence of intermediate fossils, doom the ideas of Origin of Species to the status of theory. Nothing about this charge would have upset Darwin. Indeed, he said as much himself in Origin of Species, devoting sections of the book to “Difficulties on Theory,” and “The Imperfection of the Geological Record.”

Where critics see lemons, Darwin saw lemon meringue pie (recipe circa 1847). While Renaissance scholars once aspired to certainty in the study of nature, this had changed by the 19th century as naturalists realized that the “see it with my own eyes” standard of proof worked poorly in trying to understand phenomena that took place far away or in the deep past. Indirect evidence could never yield certainty, but it could be used to develop provisional ideas that gained or lost strength on their ability to account for new data. By this standard, Darwin’s two theories, evolution and natural selection, have held up amazingly well over the past 150 years. That Darwin was comfortable in accepting his work as “theory” may seem like evolution’s Achilles heel to Creation Scientists and Intelligent Designers, but it is exactly this feature which places his research firmly within the era of modern science.

Thanks to Dr John van Wyhe, Director of The Complete Works of Darwin Online, for permission to use Darwin Online images for this post.

Other posts on Darwin:

Digital Archive: Charles Darwin

Darwin Sites and Blogs:

History of Science in the 19th Century: