Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationTurkey, Tradition, and the Lagrangian Point

Thanksgiving, that magical day, a time of gathering, fellowship, and unrestrained serial eating. Like all holidays, Thanksgiving unfolds in the present, tethered in complicated ways to the past. “Tradition” probably best describes these personal, historical, links. Consider turkey. We eat turkey in our house because we like it, it keeps well, and can be transmuted into any number of post-Thanksgiving dishes: turkey soup, turkey sandwiches, turkey fricasse. But turkey remains on the menu every year not only because of its tastiness and longevity, but because it’s always been on the menu, seared as it is into the mystic chords of turkey memory. I cannot think of a time when we considered having something else for Thanksgiving. Such is the power of tradition.

Exploration has its own traditions, ways that link current endeavors to historical precedents. Some of these traditions are obvious enough, such as the naming of vessels, probes, etc. in honor of previous people or ventures: Galileo, Cassini, Enterprise, and Challenger. But others are more difficult to detect without hindsight. Many explorers prided themselves on being careful empiricists, objective observers of the regions they described. Reading these works now, however, its hard to miss the imprint of culture on their narratives, the martial descriptions of exploration as a “war on nature” and the kindly, patronizing descriptions of native peoples as “children of nature.” These tropes were also traditions of a sort.

Yet some things are still hard to see with the benefit of hindsight, even when they are staring at you in the face. Consider Dan Lester and Giulio Varsi’s article at the Space Review on the current Vision of Space Exploration. Lester and Varsi observe that NASA’s tradition, implicit (perhaps unconscious?) has been to associate exploration with solid places, rocky grounds suitable for “footprints and flags.” There are good reasons for going to the Moon and Mars, particularly for astrogeologists who want to know more about, well, the Moon and Mars.

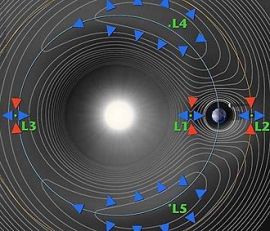

But what about those scientists who seek to uncover more about the broader galaxy? This is a form of exploration best conducted remotely, with telescopes, rather than suited-up astronauts. For these purposes, the Moon and Mars are not ideal locations. To get the most bang for the buck, telescopically speaking, NASA would send its space telescopes to one of a number of “Lagrange points,” regions of space where telescopes could remain stationary relative to larger objects such as the Earth and Moon. Freed from planetary surfaces, these telescopes could observe broad reaches of the sky, unencumbered by planetary atmosphere or blind spots.

Costs and operational simplicity seem to favor by a large margin locations in free space such as the Earth-Sun Lagrange points over the lunar surface. While lunar soil may offer a record of solar activity that is valuable to heliophysicists, realtime monitoring of the Sun and the solar wind does not need to be anchored on regolith. Overall, the lunar surface presents a challenging environment, with dust and power generation problems as well as the difficulty of precision soft landing.

Relative to the push for human exploration of the Moon and Mars, “Lagrangian exploration” is a low priority for NASA. Why? Perhaps, as Lester and Varsi observe, it’s because of the historical importance of discovering land, of sinking one’s feet into the soil and then planting a flag in it.

As I read this article, it suddenly made other pieces of historical data fall into place. When Robert Peary and Frederick Cook brought back their photographs of the North Pole, why did both men choose to plant their flags in the highest hummock of pack-ice they could find? No such location would have been identifiable so precisely from astronomical calculations (if indeed either of them reached the North Pole, which I doubt). Clearly then these men had other reasons to plant the Stars and Stripes on a high hummock, rather than, say on a flat stretch of pack ice or floating on the water of a “lead.”

Clearly “earthiness” remains a tradition in exploration, an element that remains in the western imagination of discovery. When the nuclear ice-breaker Yamal steamed north in 2000 with its burden of high-paying tourists bound for the North Pole, it found open water there. What to do? The party could have celebrated the watery top of the world from the deck. Paddled around it in inflatable boats! Instead the Yamal steamed south far enough to reach solid pack ice. There the crew planted the “North Pole” flag around which the passengers danced, celebrating their attainment (kind of) of the top of the world.

Maybe its time to break tradition.

(This is a repost of 9 August 2008’s “A Place to Plant the Flag”)

Interview with Beau Riffenburgh

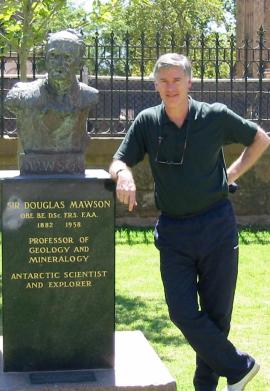

Beau Riffenburgh next to a bust of Sir Douglas Mawson at the University of Adelaide, South Australia, AU

History of exploration was just becoming a hot topic in the Academy when I started my graduate work in the mid-1990s. Academic interest attached itself to post-colonial studies, focusing on regions of the globe where Europeans and Euro-Americans had done most of their empire-building: Asia, Africa, and the Atlantic World.

The world of Polar exploration, however, remained quiet, a terra incognita of historical scholarship. Meanwhile, non-academic historians were churning out polar books in droves, on Robert Peary, Robert Falcon Scott, Ernest Shackleton and others. I suspect that all of this attention caused academic historians to shy away even further, to view polar exploration as suspect, a popular rather than serious subject of inquiry.

It was in this environment that Beau Riffenburgh published his pathbreaking book Myth of the Explorer. Here was a scholarly approach to a “popular” subject, in this case a behind-the-scenes look at the most sensational explorers of the Victorian World. Riffenburgh’s book shattered explorers’ claims to be men of a different world, men built of a different mold. It showed how deeply embedded these men were in the world they left behind, in their values, their careers, and their financial dealings.

Myth of the Explorer thus offered academic historians a bridge to the other side, a way of approaching the sensational explorers with a different set of aims, a different list of questions. Although it is now out of print, Myth of the Explorer remains an essential resource for historians of Victorian exploration and it is cited in the works of Robert Kohler, Felix Driver, Graham Burnett, and Felipe-Fernandez Armesto. Its influence certainly extends to my own book Coldest Crucible.

It is a pleasure to welcome Beau Riffenburgh to Time to Eat the Dogs.

Your first book Myth of the Explorer looked beyond the heroic images of explorers slogging it out in the field to examine explorers’ actions back home, particularly their financial dealings with the popular press. This was a very different kind of exploration book when it came out in 1993. What led you to the project and your approach to it?

I long had been fascinated by exploration, particularly of the polar regions and Africa. I decided after working a number of years in publishing to go back for a PhD just because I wanted to spend several years researching something that really interested me. I had previously earned an MA in journalism, and also had strong interest in the history of the press. My PhD thesis, upon which Myth of the Explorer was based, allowed me to use these two interests to look at the other. Since the press played a significant role in sponsoring, promoting, and creating an interest in exploration, it seemed logical to use the press of the time as a vehicle through which to view exploration. At the same time exploration could be a subject by which to test several hypotheses that I had about the way the growth and use of sensational journalism is generally presented in studies of the history and development of the press.

How was it received?

In general, the book was received very well by reviewers. It was published by a small publisher, but it interested Oxford University Press enough that they sought it out to publish in paperback. I would like to think that it helped influence a number of scholars who have done studies since then.

You served as Publication director for the NFL in the 1980s, writing a variety of books about American football. Did your work for the NFL reveal to you any links between modern sports and 19th century exploration?

I was the senior writer for NFL Properties, the publishing and licensing branch of the NFL, and I essentially was director of historical research. I can’t say that my work there revealed any particular links between sports and exploration, but the switch between the two is not as bizarre as it initially sounds. I was one of several people around the country who conducted a good deal of research on what was sometimes known as the Ohio League, the informal grouping of professional football teams in Ohio and a few surrounding states before the founding of the NFL in 1920. This included many of the teams that went on to join the NFL, such as the Canton Bulldogs. I would like to say that the foremost scholar in this field, and one who is a marvellous researcher, is Bob Carroll, an independent researcher who lives in Pennsylvania and was the key founder of the Pro Football Researchers Association.

Anyway, the main point here is that much of this research was carried out by carefully going through old newspaper accounts of football games in order to obtain data held there but seemingly otherwise lost. When I began my PhD, I continued using nineteenth-century newspapers as my primary data source, and was able to use essentially the same collection methods. In other words, although my subject matter changed dramatically as I went to exploration, my methods remained similar, so it was not a huge change in what I had done before.

In recent years, you have published a number of trade books on exploration. Your latest book, Exploration Experience: The Heroic Exploits of the World’s Greatest Explorers (National Geographic Society, 2008) combines your essays with reproduced documents, photos, and artifacts from famous expeditions. How did the experience of writing Exploration Experience and these exploration books differ from writing Myth of the Explorer?

My two major books of the past five years have been Nimrod (published in the US as Shackleton’s Forgotten Expedition) in 2004 and Racing With Death in 2008. The first was the first account of the first expedition led by Ernest Shackleton, the British Antarctic Expedition (1907-09), on which he attained a farthest south. The second is an account of Douglas Mawson’s Antarctic expeditions, primarily his Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911-14), on which he made perhaps the most amazing Antarctic journey ever. Both of these are scholarly books, written after extensive research in the archives where original materials are held, but, hopefully, written in a manner than will appeal to a general reader. I believe strongly that there is nothing stopping a book from being both scholarly and interestingly written.

Exploration Experience is a different type of book, in that it is heavily illustrated and contains, as you mention, memorabilia from numerous expeditions. Moreover, it is an attempt to give a look at the overall history of exploration, touching on the highlights rather than giving extensive detail about any one expedition. It was fun to write because it includes accounts of exploration in Asia, South America, Australia, and other areas that I had not written extensively about previously. The text is not one long narrative, but rather shorter highlights about different expeditions, so it is a totally different — but equally enjoyable — writing technique.

These differed from Myth of the Explorer in that they were more aimed at a general audience, whereas all along I felt that Myth of the Explorer would be more appropriate for a more specialist audience. I would like to think that all of them are enjoyable reads, but I think it is safe to say that Myth of the Explorer was not something that would grab the exploration enthusiast so easily as my more recent books.

Myth of the Explorer offered a sober, often critical portrait of Victorian explorers. Trade books on exploration, however, tend to be more forgiving of explorers’ motives and actions. Do you feel any tension in moving from one genre of writing to the other?

No, I try to follow the academic process throughout. I collect and analyze data and then present it in a fashion that I feel is fair, hopefully unbiased, and hopefully interesting. Nimrod, once to the ice, is, I hope, an exciting tale of adventure, but the materials for it were still compiled carefully and following the same “rules” of research as Myth of the Explorer. Since I have been writing and editing for a living for more than 25 years, stylistic changes in books are not excessively difficult to make, as shown by the fact that I have written a different book on a different aspect of the Mawson story in a different style. I hope it will be coming out in a year or so.

As an American living in England, you’ve had ample opportunity to compare national cultures. Do Britons and Americans think differently about exploration?

I can’t say that I think folks in Britain and the us think differently about the processes of exploration, but there tends to be a different emphasis perhaps. Regarding the polar regions, older generations in the UK grew up with the story of Robert Falcon Scott as something that everyone knew, and he was a great imperial hero, along the lines of Livingstone or Gordon. Perhaps because of this, and because of the Shackleton connection, in recent decades the Antarctic tends to have been a stronger general interest than the Arctic. The greatest American polar hero, on the other hand, was Robert E. Peary, an Arctic explorer. So although this is a huge generalization with all of the weaknesses that can be expected to accompany it, one finds a bit more Antarctic interest and knowledge in the UK and a bit more Arctic interest and knowledge in the US. This has somewhat changed with the Shackleton-mania that swept through the US and with the growth of tourism to the Antarctic, but it is at least a broad difference. And none of this is to say that neither country had any interests in the other region, as obviously Byrd was a great American hero and the British had any number of Arctic expeditions. Similarly, most Americans will learn more about Lewis and Clark and other explorers of North America, while many folks over here will be much more familiar with African exploration, for which many British explorers were key figures, such as Livingstone, Burton, Baker, etc.

What do you think about the United States’ current Vision for Space Exploration, a plan to send astronauts back to the Moon and ultimately to Mars?

I think that space exploration is very exciting. However, I do think that it is a totally different process than the exploration that was carried out in the nineteenth century. Then, to a great extent, it was based on man’s heart, will, and personal strength and determination. Now the man going into outer space would play a key role, but a very different role, since he is a part of a much larger package that requires a great deal more technological involvement. I think that much of the shift has been from man’s inner strength to his intellect.

What’s your next project?

I am currently working on a follow-uo to Exploration Experience that concentrates on polar exploration, using the same format. I am also hoping to write a lengthy book about an explorer in a totally new (for me) area of the world, but I have been asked by the potential publishers not to discuss it at this time.

A mystery to whet the appetite. Beau, thanks for speaking with us.

Digital Archive: Conrad Martens

Before I starting working on the frost-bitten, scurvy-riddled, dog-eating world of Arctic explorers, I researched more inviting places, such as Valparaiso Chile, “the Vale of Paradise.” In the 19th century, Valparaiso was a popular port for European and North American voyagers, a place for crew to load up on provisions, repair hullwork, mend sails, and dive into debauchery before the long sail across the Pacific.

The U.S Exploring Expedition stopped here, as did the U.S. Astronomical Expedition, and even HMS Beagle, disembarcking a sprightly young, recently-graduated Charles Darwin into town for some quick surveys of the Cordilleras before heading out into the Pacific (with a minor port-of-call in the Galapagos on the way). My masters thesis “Describing the Vale of Paradise: Valparaiso Chile in the Years after Humboldt” looked at the way these various scientific expeditions talked about Valparaiso, and more importantly, how they rendered it in images.

Darwin did not leave much in the way of illustrations of the town, but the Beagle’s draughtsman, Conrad Martens did. Martens’ landscapes are quiet, almost languid, places, a world apart from the pulse-pounding wind-swept, volcano-erupting landscapes of his fellow Romantics. As I sat in the stacks of the Wisconsin Historical Society looking at these far away places, they gave me a feeling of Darwin’s world…an imperfect impression to be sure, but a feeling nevertheless. Thanks again to the Beagle Project Blog, great conduit of all things Darwin, I have learned that Martens work is now available for all to see at the Cambridge University Library’s website. They have scanned two of the four extant Martens sketchbooks made from the voyage. They include, be still my heart, lovely Valparaiso.

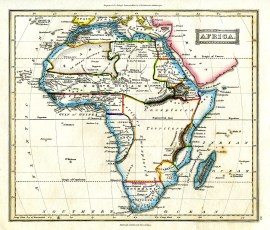

Digital Archive: AfricaBib

Mary Kingsley, African explorer, ca 1890

For me, graduate school was a happy time, of long days in the archives and long afternoons in the Ratskeller. To be fair though there were also moments of fear: fear of discovering some document that would blow apart my thesis like a howitzer shell. Or worse, fear of finding some book that supported my thesis, indeed supported it so closely that it would render my project superfluous, a poor knock-off of the original. Neither of these happened, though I did have my queasy moments of discovery in the card catalog.

“Der Bücherworm” by Carl Spitzweg, 1850

I calmed my fears by mastering the ways of the database: Historical Abstracts, America: History and Life, the Making of America, Poole’s Periodical Database, Periodical Content Index, Dissertation Abstracts International, the American Periodical Series, etc, etc etc. Database companies market their products as tools for research and networking. And indeed they are. But for the paranoid graduate student, databases are used as radar, informing them when another scholar is flying too close. Happily those days are gone. But I still get a warm, cozy feeling inside when I find a good database. It is researcher’s version of a hot toddy.

Such was my feeling last night when I found AfricaBib, a set of three databases about Africa, the most exciting of which is Women Travelers, Explorers, and Missionaries to Africa. The databases are a thirty-year labor of love by research librarian Davis Bullwinkle who started working on the project in 1974, using, no doubt, index cards. As the project grew, Davis began to upgrade to a computer filing system, one designed by the precocious computer-whiz son of a colleague. After Bullwinkle retired in 2008, the database was taken over by the African Studies Centre (ASC) in Leiden, the Netherlands who keep it up to date. The database currently boasts 1800 items. What does this mean in terms of finding material on women explorers? Playing around with the database last night, I entered “Mary Kingsley” into the keyword search. It pulled up 109 records, including published dissertations, scholarly articles, books, and online essays. Very impressive. Nice work Davis.

For more on women travelers and explorers, see my post on Gertrude Bell and Women Explorers

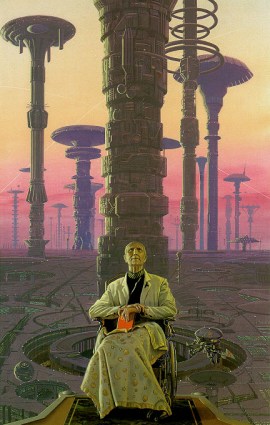

Nate Silver, Baseball Analyst, Prophet of the Galactic Empire

Like most of the free world, I spent October following the U.S. presidential election. For me this meant looking over the dailies, a graph of the national tracking average, and a red/blue map of the Electoral College. This was about the extent of my political forecasting. Not so Nate Silver, statistical boy-genius, baseball analyst, and author of the political projection site FiveThirtyEight.com. Silver’s predictions have caused quite a stir because they have been so prescient. Based on his analysis of polls, he called the election for Obama. . . in March. Call him lucky. Then he predicted 49 of 50 states correctly on election night with a 6.1% margin for Obama, within 0.4 of the actual margin. Silver can add these to a growing list of oracle-like achievements: calling the results the Super Tuesday within 13 delegates (out of 847), predicting the ascendency of the Tampa Bay Rays and the 90-loss season of the Chicago White Sox. Silver now markets a number of statistical models including PECORA, QERA, and SECRET SAUCE (an algorithm for the Big Mac?).

Silver’s uncanny ability to predict things that seem murky to the rest of us reminds me Isaac Asimov’s Foundation Trilogy, published in 1951-53. Asimov’s story is set in a Galactic Empire which contains thousands of inhabited planets and quadrillions of human beings. The stunning size of this empire allows one man, Hari Seldon, to develop a set of statistical models for predicting the future of civilization, a field of study he calls “psychohistory.” Seldon’s algorithms have no ability to predict the actions of a single individual, any more than one could predict the toss of the coin. The single flip is always unknowable, but not so a hundred flips, a thousand, ten thousand, a series that becomes more predictable with each iteration. It is a science which gains precision as the data aggregates.

The story of Silver and Seldon make for good reading. But they also touch upon a very storied debate among historians about the forces that propel history. For centuries, scholars viewed this force (or “agency” as it is called in the Academy) as a power contained within the individual. In other words, one could understand the ebb and flow of empires by following the actions of powerful individuals: popes, kings, and revolutionaries. Certainly this continues to be a popular way of looking at the forces of history, as can be seen by the hefty shelf space afforded “Biography” at Borders and Barnes and Nobles. But among academic historians, the “Great Man” vision of history has lost much of its blush. Individuals continue to matter, but to many of us, the agents of history reside in the realm of the extra-human: institutions, churches, states, and the ephemeries of culture.

Nowhere was this more apparent than in the French Annales School of the early 20th century. Its founders, Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre grew tired of the emphasis on individuals and big events: wars, coups, congresses, and assassinations. Instead they saw history as a tectonic thing, a gradual unfolding of events caused by millions of people influenced by their habits, geography, and material culture. Here in episodes of “longue durée” lay the true causes for the rise and fall of empires.

So welcome Nate to the world of many parts. We expect big things.