Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationThe Night Before Christmas

In the spirit of the season, here’s a version of The Night Before Christmas using some of the search terms that people have used to find Time to Eat the Dogs. (My blog software informs me of these search terms in an ever-growing list). Thanks for all of the great comments and suggestions over the past year. Drive safely, eat well, and I’ll see you next year.

The Night Before Christmas

‘Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house

Not a creature was stirring, not even a cyclops;

The stockings were hung by the chimney with care,

In hopes that Ernest Shackleton soon would be there;

The ancient naked men were nestled all snug in their beds,

While visions of misshapen world maps danced in their heads;

And mamma in her ‘kerchief, and Thor Heyerdahl in his cap,

Had just settled down for a long winter’s nap,

When out on K2 there arose such a clatter,

I sprang from my high altitude human balloon to see what was the matter.

Away to the laminar flow hood I flew like a flash,

Tore open the shutters and threw up the sash.

The moon on the breast of the new-fallen snow

Gave the lustre of mid-day to objects below,

When, what to my wondering eyes should appear,

But a mad magazine evolutionary chart, and eight tiny reindeer,

With a Peruvian tribe, so lively and quick,

I knew in a moment it must be St. Nick.

More rapid than dinosaurs his coursers they came,

And he whistled, and shouted, and called them by name;

“Now, Mallory! now, Darwin! now, Armstrong and Peary!

On, Wallace! on Aldrin! on Martens and Kingsley!

To the top of the world! to the top of the wall!

Now dash away! dash away! dash away all!”

As dry leaves that before the K-T extinction event fly,

When they meet with an obstacle, mount to the sky,

So up to the space rover the coursers they flew,

With the sleigh full of toys, and Shackleton too.

And then, in a twinkling, I heard on the roof

The prancing and pawing of turkey fricassee.

As I drew in my hand, and was turning around,

Down the chimney Shackleton came with a bound.

He was dressed all in fur, from his head to his foot,

And his clothes were all tarnished with ashes and soot;

A bundle of strange maps he had flung on his back,

And he looked like John McCain just opening his pack.

His eyes — how they twinkled! his dimples how merry!

His cheeks were like roses, his nose like a cherry!

His ancient order of foresters was drawn up like a bow,

And the beard of his chin was as white as the storm over Everest;

The stump of a hominid he held tight in his teeth,

And the smoke it encircled his head like a wreath;

He had a broad face and a little crash test dummy,

That shook, when he laughed like a sled-ful of jelly.

He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf,

And I laughed when I saw him, in spite of myself;

A wink of his eye and a twist of his leviathan,

Soon gave me to know I had nothing to dread;

He spoke not a word, but went straight to his work,

And filled the SSV Corwith Cramer; then turned with a jerk,

And laying his finger aside of his nose,

And giving a nod, up to orbit he rose;

He sprang to his Mars Phoenix Lander, to his team gave a whistle,

And away they all flew like the down of a thistle.

But I heard him exclaim, ere he drove out of sight,

“Road trip” and “I need to escape modern life”

Contingent World, Part 2 of 3

Last week I wrote about unpredictability, mainly as it applies to the sciences. But one doesn’t have to understand evolutionary biology or chaos theory to appreciate the real-world significance of contingency.

Crashing your bike, for example, is a highly contingent event, balancing on the fulcrum of the tiny circumstance: the patch of black ice or the open car door. Careening into the pavement, one feels keenly the power of the unforeseeable cause. Yet other events, such as weddings, usually unfold according to predetermined paths and produce predictable outcomes. Indeed, wedding planners make their living on this assumption, convincing couples that certainty is achievable, that contingency can be banished from church and reception hall.

All of this is to say something that is probably already pretty obvious: some events are more predictable than others. Historians have no quibble with this. The more interesting question is this: what kind of events matter? Which of them are the movers of history? (Or, as a historian might phrase it, which forces have the most historical agency?).

Karl Marx

For some, the power of contingency remains a relatively minor factor in history, dwarfed by the unfolding of large-scale, long-term events. Karl Marx’s theory of historical materialism, for example, sets up a series of stages (Feudalism, Capitalism, Socialism, Communism) that societies pass through as people try to fulfill their basic needs. In Marx’s vision, societies evolve according to a pattern which cannot be easily upset by contingent forces. History is a supertanker which moves through the water with a momentum scarcely touched by the people on deck, no matter how unpredictably they might be acting.

On the other hand, there are the proponents of “great man” history who tend to place the course of events in the hands of individuals who make decisions that change the world: Caesar, Napoleon, Hitler, Justin Timberlake. This vision of history tends to be far more open to the power of contingency since unforeseeable events clearly effect the lives of individuals, even “great men.” While these histories remain enormously popular and fly off the shelves at Barnes and Nobles, they are seen as rather old-fashioned in the Academy. Here among the turtle-neck and tweed-jacket classes, the “great man” has been replaced by a focus on other agents: institutions, states, empires, or culture.

Yet even with the interest in big-scale forces such as institutions and empires, the idea of contingency has gained caché within the Academy. For many it is clear that institutional or imperial events also do not have predictable outcomes, unfolding in surprising ways with unforeseeable consequences.

The irony in all of this is that historians are largely to blame for making history seem inevitable. It is not for want of trying. Historians, even more than political analysts, do Monday-morning quarterbacking, bringing coherence to events that benefit from the wisdom of hindsight. This is what we do. Yet the irony is that, in bringing coherence to seemingly chaotic events, we loose something of the reality of the event as it unfolded.

The hardest part of history, as I see it, is not in chasing down and explaining these events. It’s in conveying the sense of open-endedness that people felt in living through them.

Contingent World, Part 1 of 3

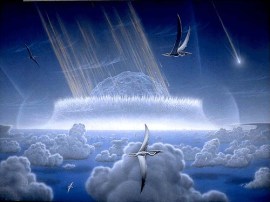

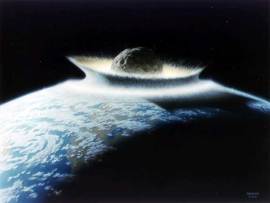

Artist Rendition of the K-T Extinction Event

A month ago, I wrote here about about Nate Turner and statistical prediction. The post discussed forces big, slow, and predictable. It got me thinking about the opposite side of the spectrum: of forces short, swift, and unpredictable. So for the next couple of posts, I’m going to dig into this a bit, starting with politics.

In the next two weeks, election officials will finally decide Minnesota’s senate race between Norm Coleman (R) and Al Franken (D). Out of 2.8 million votes cast, Coleman and Franken are now separated by about fifty votes. I would like to remain optimistic about this but let’s face it: with such a narrow margin, it’s almost guaranteed that the loser will bring charges of fraud, lost ballots, etc.

Norm Coleman and Al Franken

After the fireworks are over, we will see a slow coming-to-terms by the losing campaign, a Kübler Ross-ian transition from bargaining to depression to acceptance. As this occurs, we will also see “what if” stories blossom like desert flowers. Pundits and reporters will talk about how small changes in events, message, or media would have produced a different outcome.

The last bloom of political “what if” stories followed the 2000 U.S. presidential election. With great wailing and gnashing of teeth, Democrats tried to make sense of an election in which Al Gore won the popular vote yet still lost the election to George Bush. Razor thin victories for Bush in a number of battleground states, most famously Florida where he won by 537 votes of 6 million cast, fueled speculation about the many ways the election could have turned out differently.

Nader the Raider by Bill Day

For many, the spoiler was Ralph Nader, leader of the Green Party, who drew votes away from Gore. For others, it was the dysfunctional Florida voting system. Still others blamed Katherine Harris, Florida State Attorney General, who confirmed the official vote count. Or the Supreme Court. Or Gore himself, who seemed so overstarched as a candidate that he even lost his own state of Tennessee.

In a sense, they are all correct. Any number of factors could have tilted the election in Gore’s favor. In the language of the Academy, we would say that the 2000 presidential election was highly contingent: the outcome wasn’t set in stone. It could have turned out differently.

As an idea, contingency has considerable heft across the disciplines of the Academy. On the science side, evolutionary biologists, have written extensively about the degree to which evolution depended upon contingencies of the environment, that the concept of fitness does not only apply to the fleetest fox or the brawniest buck, but sometimes to the dumb luck of being well adapted to an unforeseeable event. Steven Jay Gould writes about this in regards to the middle-Cambrian organisms discovered in the Burgess Shale Formation.

Castorocauda lutrasimilis, the "Jurassic Beaver," survivor of the K-T extinction event.

Better known to the rest of us are early mammals who managed to win the Darwinian lottery by being around when a comet the size of Manhattan plowed into the Earth 65 million years ago. Although the evolutionary implications of this event are still hotly debated, few doubt that something big happened to disrupt ecosystems all over the world, ultimately leading to the extinction of the dinosaurs.

The K-T extinction event, as its called, makes clear an important point: even if history of life on earth is based upon slow, incremental changes to species over time, its evolutionary course was unpredictable. Life, like the Cretaceous comet of death, could have taken a different path. Had it done so, perhaps we would all be frightened weasel-like creatures, stealing our food in the shadows of brontosaurs and pteranodons. (For more on weasels and evolution, visit John Lynch’s Stranger Fruit)

Contingencies do not have to be comet-sized, however, to have big effects. Such was the discovery of meteorologist Edward Lorenz who found that weather simulations produced wildly different outcomes based upon minute changes in initial conditions. From this, Lorenz coined the term “Butterfly Effect,” the idea that the flapping of a butterfly’s wings might change the atmosphere enough to create (or prevent) a tornado from occurring at some future time.

Lorenz’s ideas are now a part of a larger corpus of work on chaos theory which shows the stunning effects of contingency (or as mathematicians call it, a ‘sensitive dependence on initial conditions’) in phenomena as disparate as air turbulence, irregular heart beats, and the eye movements of schizophrenics.

All of this happens at some distance from where I sit in the humanities, surrounded by books on art, maps, and social history. Yet contingency plays a critical role here too, something I’ll take up in my next post.

Lessons of the Free Solo

Steph Davis free soloing The Diamond, Longs Peak, Colorado

As a student of exploration, it would be fun to tell you that my eureka moments come at the end of long days of dog-sledding, bear-wrestling, and artifact-gathering. In truth, there are very few eureka moments and no bears. Most of my discoveries appear in hermetically-sealed, humidity-controlled Special Collections rooms. I’m usually wearing cotton gloves and the librarian watching me has taken away my pens.

The Special Collections Room

But I had a eureka moment last night, ex bibliotheca. I was at a holiday party, sitting with a small group of people I had never met, cradling a large gin and tonic. We took on a whirl of topics: Apple computers, school bus driving, Thai massage, history education, and technical rock climbing. On this last point, people had much to say because, despite our different backgrounds, everyone was either a hiker or rock-climber. (This might seem a remarkable coincidence except for the fact that our hosts, Michael Kodas and Carolyn Moreau, are uber-climbers themselves, something probably reflected in their pool of guests).

Gerry, sitting to my left, picked up a copy of The Alpinist and showed me an article about solo free-climber Steph Davis. In the article, Davis is free climbing an outrageously sheer cliff, the “Pervertical Sanctuary” of 14, 255 ft Longs Peak in Colorado. Davis has no ropes, no parachute, no net, no way of preventing death if she falls.

Steph Davis

“What’s up with this ?” I asked Michael (not Michael Kodas), a highly skilled rock climber to my left. “I mean, after all, would ropes and harness be that much of a buzz-kill?”

“Ultimately it’s about focus. The climber has to be in the moment. Make this hold or die. Now the next one. Now the next one.”

Although Michael uses ropes, he remembers his most dangerous climbs with searing clarity: the texture of the rock, the shape of the flake, the tortured movements he uses to pivot his body in space.

Although I write often about the commercial hypocrisy of Arctic explorers of old (and some Everest climbers of new), I can appreciate the beauty of a mind in focus. It shines brightly to me through the thicket of distractions, of cellphones and Blackberrys, of text messages and twittering feeds, of listservs and Netflix deliveries. The ability to cast one’s mind on something and fix it there is powerfully appealing.

Would I dangle my body off a 4000 ft cliff to find it? Probably not. But I understand how intoxicating others would find it. And this bears on a bigger issue. Sometimes it’s easy for historians to forget the human beings behind their historical subjects. Or in my case, to see explorers’ drive for fame and glory and forget the powerful psychological underpinnings of dangerous travel. Historians do this on purpose, I think, for fear of imparting motives that are not borne out by the texts. After all, it’s easy to track faked photos, product endorsements, and publishing contracts, but harder to read minds and motivations. And yet these psychological motives are real, something I need to take more seriously in my work.

So to Michael, Gerry, Nikki, Trace, and Topher, it was great to meet you last night. Thanks for including me on your voyage of discovery.

The Gertrude Bell Archive

Gertrude Bell and Sir Percy Cox, Mesopotamia, 1917

Gertrude Bell and Sir Percy Cox, Mesopotamia, 1917

My students are usually pretty good at the why questions of history. Why did the French revolt against their King? Answers include “Peasant frustration.” “Anger at the monarchy.” “Expensive bread.” It’s the when questions that cause students trouble. Why did the French revolt in 1789? What particularities of this historical moment led to the great unraveling of the French Monarchy?

This pattern holds true for discussing women in history, or more specifically, the actions of women travelers and explorers. Why did Annie Peck climb the Matterhorn (1895)? Or Fanny Bullock Workman the Himalayas (1899-1912)? Why did Mary Kingsley canoe her way up the Ogawe River in Africa (1895)? Or Nelly Bly circle the globe in 72 days (1889)? Student answers usually come in some variety of “They had to prove something to the world.” Ok, fair enough. But here is the more interesting question: Why did they all feel the need to prove it at the same time?

Mary Wollstonecraft certainly felt she had something to prove. Enlightenment novelist and historian, philosopher and feminist, Wollstonecraft authored A Vindication of the Rights of Woman a full 136 years before Britain fully granted women the right to vote in 1928. But living at the end of the 18th century, Wollstonecraft is something of an outlier in women’s history, a person whose beliefs and actions were at considerable remove from the rest of society. Peck, Workman, and Bly, by contrast, were part of a large social movement that extended across the Atlantic, a movement that gleefully assaulted the idea of a “separate spheres” for men and women.

Fanny Bullock Workman holding up "Votes for Women" sign at 21,000 ft

In this sense, Gertrude Bell was a women of her time: born in Britain, Oxford educated, Bell was an omnivorous learner and traveler, fluent in Persian, Arabic, Turkish, and German. She voyaged around the world twice and took up a passion for mountain climbing in the Alps all before “settling down” in the Middle East as archeologist, author, and British political agent during the First World War. She collaborated with T.E. Lawrence to draw up the modern political map of the Middle East including Jordan and Iraq. Yet Bell remains hard to categorize. Sitting at the center of British political activity in the Middle East, Bell also served as honorary secretary of the British Women’s Anti-Suffrage League.

Bell left 1600 letters, 16 diaries, and 7000 photographs, all of which are in the possession of the University of Newcastle upon Tyne. Now the University Library has begun a four-year project to put these materials online. Here for example is Bell’s description of her ascent of the Aiguille du Géant in the Alps:

Demarquille was frozen. I gave him my big woollen gloves. My hands were warmed by the rock work, but I continued to shiver, though not unpleasantly, almost until we returned to the foot of the Aiguille. We crossed a bit of snow and turned to the left under the Aiguille where we found a hanging rope – it was just about here that a guide was killed a fortnight ago by lightening, after having accomplished the ascent by a new road up the N face said to be easier than the old. The first hour or so was quite easy. Straight up long slabs of rock with a fixed rope to hold by. Then a flank march which was rather difficult; the rocks from here to the top of the NE summit are extremely steep. At one point my hands and arms were so tired that I lost all grip in them. A steep bit down, a pointed breche and a very steep up rock leads to the highest summit where there is a cairn.

The Gertrude Bell Archive is a work in progress. Not all of the materials have been scanned. It does not have keyword or full-text search capabilities. Still it deserves to be filed as a bookmark in your growing list of exploration archives.

For more on women explorers, see posts on