Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationNew Worlds

Life cover from 22 February 1954 featuring shot of film 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea

At times I think about getting rid of my laptop, dumping it into the trash or tossing it over the guardrail on I-84. It works perfectly fine. But its role in my life increasingly bothers me. It feels invasive, a tool that has become a crutch, mediating almost all of the activities of my life: my communications with students, friends, and colleagues, my meeting place for committees, spreadsheet for calculating grades, library for reading newspapers and searching archives, store for ordering books, entertainment center for films, sports pages, and blogs.

I find myself thinking — dolefully, wistfully — of paper and pencil, of writing notes on index cards, thwacking out papers on a typewriter, writing letters on rough-edged stationary, reading books slowly and deliberately on my couch rather than gutting them like fish on the deck of a ship.

Most of all, I don’t like what my laptop does to the way I think. I used to spend a great deal of time tunneling in on subjects, digging into the arcana of history like a wood bore. Now I feel I spend a great deal of time skittering over subjects, a flat rock thrown over a calm pond. I cannot place all of the blame on my laptop. It comes from having too many things to do.

Being too distracted is a lament common to Americans and Europeans since the 18th century. Do our lives benefit from the conveniences of modern life? Or are these conveniences a subtle gloss that separates us from the vibrancy of raw experience? A laminate that protects us from the authentic life? Or, as Thoreau puts it:

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear… [Walden, ch. 2]

I think Thoreau draws this dichotomy a bit too starkly. My feeling is that all of life is authentic; experiences are real no matter how mediated they are by technology or modern convenience. Still I’m not letting my laptop completely off the hook. For all of its impressive powers, the networked computer is crack cocaine for the skittering mind, the gateway drug of associational thinking.

Still, I won’t throw it away. First, it doesn’t belong to me and I would have to pay back my dean. Second, it has brought me into contact with fascinating people and amazing places, a New World of information that I absorb in bits and pieces.

Ok, enough deep thoughts. Here are some new links I’ve uncovered in my skittering hops across the pond.

Google recently worked out a deal with Life Magazine, scanning decades of photos and putting them in a historical archive online. This is a fabulously rich collection of twentieth-century images, particularly in the field of exploration. Try out, for example, terms such as expedition, voyage, underwater, capsule, and planet. You can also search Google for life photos directly – just enter your search term followed by “source: life”. When this returns a list, specify “images” in the tab at the top.

The Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library offers a much smaller set of archival images, five to be exact. But the five images in question, European maps of discovery from 1520-1792, are too rich to be missed. Each map offers a snapshot of European geographical knowledge of the world, from the shape of continents and novel modes of map projection, to elaborate cartouches showing the lifeways of native peoples.

Finally two sites I just learned about today. The first is Big Dead Place, an online journal devoted to Antarctica, edited by Nicholas Johnson, author of a book of the same name published by Feral House Publishing in 2005. Johnson has some great interviews and analysis of South Polar exploration.

For an impressively massive list of all things Antarctica, also check out Dr. Elizabeth Leane’s Representations of Antarctica which breaks up the subject into categories of fiction (juvenile and adult), short stories, poetry, films and television, as well as literary and cultural criticism.

The Smudgy Window of History

Stephen Dobyns

It is sunny, cold, and quiet here in Hartford. No one is out. Everyone, it seems, is waiting for the big storm that will roll through this afternoon. It seemed a good opportunity to sit down with Laura Waterman’s book, Losing the Garden, a memoir about Waterman marriage to Guy Waterman and the events leading up to his suicide on Mt Lafayette in 2000. I didn’t even make it to the first page, though, because I was rather struck by Stephen Dobyns’ epigraph:

It is hard for me to say what is precisely true. Memory distorts. Psychology, emotions, good health or bad — all drag their feet across events. The details that I might remember one day are not those that I might remember on another day. And certainly my memory has its own agenda — to show me off this way or that. My subjectivity is the smudgy window through which I squint. [Stephen Dobyns, quoted in Laura Waterman’s Losing the Garden]

In this simple, elegant paragraph, Dobyns expresses an idea that is at the core of academic history: the perils of subjective experience.

For historians, there are two parts to this.

The first: beware the recollections of your subject. People remember events in ways that are selective and distorted. Often these distortions of memory increase over time. Oral historians often find that subjects interviewed forty or fifty years after a particular event remember it in ways largely at odds with the records they kept at the time.

The second: beware the distortions of the storyteller. Many of my students think of history as a fixed series of events that have been culled from the documents, dutifully analyzed, and then set down in stone (or in their case, textbook) for the ages to admire.

Historians, however, are much more aware of history as a living thing, something in continual motion, pushed, pulled, or turned upside-down by scholars of the present. These changes do not emerge from the discovery of new historical data (although this happens too), rather because historians cannot help but bring their own interests, beliefs, and preoccupations to the subjects they study. As culture changes, so do historians and the histories they write.

George Washington

One sees the dangers here. If one carries too much of ones beliefs back into the past, it will dominate one’s thinking. We could write a factual, empirically rigorous book called George Washington: Our Racist, Sexist, Non-vegan Founding Father.

But such a book would be of limited value because these labels tell us little about Washington as a unique figure. Washington’s ideas about race, sex, vegetables, etc were broadly shared in the 18th century, enough to be seen as social norms in his society.

Focused on the chasm of difference between Washington and modern society, such a book would miss the subtle textures of past itself, the differences that mattered to people of the day. In the profession, we even have a name for this sin of modern bias which is called “Whig History.”

Yet the historian cannot leave modern influences at the outer door of the archive. Nor should she. As much as a historian’s ideas and beliefs are a hazard, they are also the engine of historical creativity, the force which keeps history fresh and ever-changing, even when the events we hope to understand are long ended.

To offer one example: until the 1950s, historians tended to emphasize politics and economics events, focusing on the roles of kings, ministers, and generals.

Yet the social revolutions of the 1960s made a deep impression on historians (and other academics) who became aware of the way that certain groups — women, minorities, colonial subjects — had been excluded from public discourse. Many historians took this revolution to heart, asking questions about these groups in the past.

The result was a proliferation of new kinds of histories, of peoples who had largely been ignored by earlier generations of historians. If my hypothetical book about George Washington is an example of the present’s influence on history at its worst, Lauren Thatcher Ulrich’s book A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard is an example of it at its best.

Working on the project in the 1980s at a time when women’s history had come into its own, Ulrich saw the potential of Ballard’s story to change the way we thought about gender, culture, and economics in colonial America. But to offer this story, Ulrich faced a difficult choice, one she writes about the in her own diary of 1982:

The trick would be to write something more accessible than the diary itself. Is this midwifery or bastardy– to borrow a metaphor from Mrs. Ballard’s world? Am I giving her life to the world or substituting an “illegitimate” book for a real book–hers.

Ulrich thought her book would be more valuable if she – and not Ballard – served as the ultimate storyteller. And an amazing story it is, one that illustrates Ballard’s industry and Ulrich’s genius. Yet it is also a book of its day, made possible by changes in the culture of the late 20th century. It is an example of the beauty of the present in history, of history’s undeniable subjectivity. It is the force that makes history art, not science, ever fallible, never finished, always new.

Why Expeditions Fail

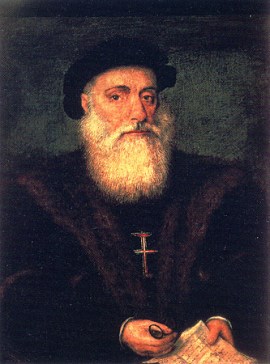

Vasco da Gama by Gregorio Lopez, 1524

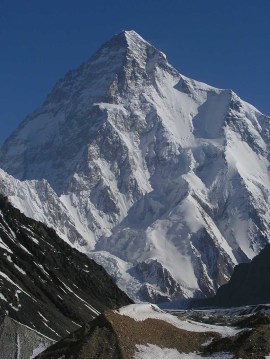

It almost goes without saying that exploration is dangerous work. Vasco da Gama left for India with 180 men. He returned to Portugal with 60. John Franklin’s 1845 expedition to discover the Northwest Passage resulted in an impressive 100% fatality rate. Even expeditions to places well-mapped and long-traveled carry risk. Planning an ascent of K2 in the Karakoram Range? Chances are better than 1 in 4 that you will die in the attempt.

K2, Karakoram Range, India

Where does danger lurk? One immediately thinks of physical and biological hazards, of gale-force winds, hull-crushing pack ice, capricious avalanches, & malarial fevers.

But these forces are only efficient causes, the sharp edge of the reaper’s scythe.

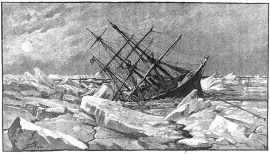

The Sinking of the Jeannette, based on a sketch by M. J. Burns, 1881

When 37 Americans died in two Arctic expeditions from 1879-1884, it was clear to everybody that the men died from starvation and exposure (well, mostly: one man drowned and another was shot for stealing food). But most Americans looked beyond these causes to contributing factors, to poor ship design and faulty relief efforts.

Yet if we look more closely, we see that, more often than not, the expedition party itself is largely to blame for its own failures. Reading the historical record, it becomes clear that one of the most difficult tasks of expeditionary life was not weathering the elements but enduring one’s peers. The 1870 Polaris Expedition to the North Pole fell apart when its pious and imperious commander Charles Hall suffered convulsions (and ultimately died) after drinking arsenic-laced coffee (probably prepared by his disgruntled science officer).

Elisha Kent Kane

For most of the nineteenth century, Elisha Kane was America’s celebrity explorer, a man revered for his eloquence, cultivation, and high-mindedness. Most of Kane’s men, however, thought he was an insufferable prig. Indeed, more than half of his crew turned against Kane in the Arctic, attempting to escape the Arctic without his approval. Almost all of this was hidden from public view, expunged from the narratives of the expedition written by Kane and his men.

The Kane Party, 1854

Still one gets subtle glimpses, even from Kane’s own work. The image above was published in Kane’s best-selling narrative of his expedition, Arctic Explorations. In the scene, Kane sits in the center, surrounded by his officers. Kane looks weary and somewhat annoyed, staring down to the right. On the right, two of his officers stare forward towards the viewer, looking at different points. On the left, two other officers are engrossed in conversation, one with a shotgun slung over his shoulder. Whispering about plans perhaps? Indeed, the only one in the scene looking admiringly at Kane is his dog. Or perhaps he’s just hungry.

These might seem like sepia-colored anecdotes from long ago. But expeditions continue to live or die on the ability of their members to get along, to communicate well, and to improvise effectively when things go wrong. Such is one of the findings of Michael Kodas who wrote about last year’s debacle on K2.

Artist rendition of Crew Exploration Vehicle (CEV) leaving Earth orbit

With this in mind, I wonder how much “unit cohesion” is on the minds of NASA’s administrators as it plans its mission to Mars. Two years is a long time to spend in a capsule with one’s mates, even with DVDs.

Contingent World, Part 3 of 3

John Muir

I didn’t plan on writing another post on contingency, but I was reading Donald Worster’s new biography of John Muir, A Passion For Nature: The Life of John Muir, and found this:

A human life, like any mountain trail, winds and twists through a very complicated, ever-changing landscape, taking unexpected turns and ending up in unexpected places. The lay of the land, the physical or natural environment, has some influence over the path one chooses to take — going around rather than over boulders, say, or along the banks of a stream rather than through a tangled wood. Likewise in the course of an individual life, nature helps give shape to the direction a man or woman takes and determines how his or her life unfolds. So also does one’s inner self, the drives and emotions that one inherits from ancestors far back in evolutionary time, determine the route. But the trail of any one’s life is also shaped by the ideas floating around in the cultural air one breathes. All those influences make it impossible explain easily why a person’s life follows this path rather than another. [Worster, Passion for Nature, 11]

Ok, the metaphor of the “life path” is a bit overused as a literary metaphor. Indeed, it was already overused in the nineteenth century before Robert Frost lofted it into cliché orbit with “The Road Not Taken” in 1916.

Robert Frost

Nevertheless, I think Worster pulls it off in talking about Muir. After all, how else should an environmental historian speak about someone who is the ultimate lover of all things path and mountain? But more to the point, I think the passage nicely encapsulates the many contingent forces that shape the life of an individual.

Fallen Giants Wins the Banff Book Award

Congratulations to Maurice Isserman and Stewart Weaver, winners of the 2008 Banff Mountain Book Award for Mountaineering History. Their excellent book, Fallen Giants: A History of Himalayan Mountaineering from the Age of Empire to the Age of Extremes , does not merely chronicle the harrowing ascents and colorful personalities of high-altitude climbing. It also offers a look at mountaineering as a cultural project that blossomed in the 19th and 20th centuries. (In the interest of full disclosure, I am friends with Stewart and an acquaintance of Maurice).

Maurice Isserman (left) receives Banff Award from Mike Mortimer (right)

David Chaundy-Smart, editor of Gripped Magazine, states:

Tilman speculated that a chronicle of the “fall of the giants” of the Himalayas would not be as interesting as chronicles of the failed attempts. He never anticipated that Maurice Isserman and Stewart Weaver would eventually paraphrase him in the title of an exhaustive and entertaining history of Himalayan mountaineering. This is a standard-setting work that credibly accounts for the struggle to summit the 8000 metre peaks with a seamless discussion of politics, economics and the development of climbing technique backed by a mind-boggling list of sources.

If this isn’t enough to satisfy your Himalayan appetite, visit the Pitt Rivers Museum’s Tibet Album. Here you’ll find a collection of British photographs in Central Tibet from 1920-1950. The collection totals 6000 photographs by Charles Bell, Arthur Hopkinson, Evan Nepean, Hugh Richardson, Frederick Spencer Chapman, and Harry Staunton among others. Taken together with Everest expedition photos of the Bently Beetham Collection (listed in my links and profiled here), one gets a vivid picture of British-Nepali-Tibetan encounters in the early 20th century.

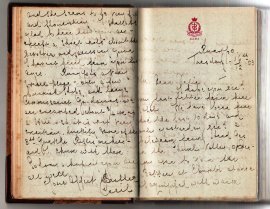

Cecil Mainprise Diary, photo from blog: Field Force to Lhasa 1903-04

You can also find the journal of Cecil Mainprise, medical officer of General Sir Francis Younghusband’s expedition to Tibet in 1903, dutifully published in blog form by his great nephew Jonathan Buckley.

Reading all of this material may give you a bit of altitude sickness. Best to descend for a while and acclimatize. I’ll be here with more after the New Year.