Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationOn Cannibalism

Sir John Franklin

In 1845 the Franklin Expedition sailed from England as the jewel of British polar enterprise. With 129 men and two steam-powered, hull-reinforced ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, the Franklin Expedition promised to deliver on the centuries-long search for the Northwest Passage.

Sir John Franklin, expedition commander, was one of the toughest, most experienced veterans of the fleet. A previous overland expedition to the polar sea had brought him to the edge of starvation and fame back in England as “The Man Who Ate His Own Boots.”

H.M.S. Erebus

Thus it was surprising when Franklin did not return from the Arctic in 1846 or 1847. In 1848, with still no word, the Admiralty sent a series of expeditions to look for him, focusing on the northern coast of America and islands off its shores. They found no sign of the expedition. Lack of news deepened the mystery surrounding the lost expedition and fueled public interest.

In 1850, the discovery of Franklin’s winter camp on Beechey Island gave hope to those that thought the expedition had traveled further west (or perhaps North into the Polar Sea) and was still intact.

But Dr. John Rae, of the Hudson Bay Company, had grisly news to report in his dispatch to the Admiralty on 29 July 1854:

During my journey over ice and snow this spring…I met with Esquimaux in Pelly Bay, from one of whom I learned that a party of “white men” (Kabloonas) had perished from want of food some distance to the westward… From the mutilated state of many of the corpses, and the contents of the kettles, it is evident that our wretched countrymen had been driven to the last resource, — cannibalism — as a means of prolonging existence.

Rae’s report touched off a furor in Britain. Charles Dickens, editor of Household Words, could not believe that Franklins’ men would have resorted to such behavior, even on the verge of death. Instead, he advanced the theory that the Inuit had probably set upon the dying party themselves.

Remains of the Franklin Party, King Williams Island, 1945

To the modern reader, the idea of eating human flesh for reasons of survival seems understandable if rather unpalatable. Why, then, was Dickens so outraged? Thirty years later, Americans would express similar outrage when the New York Times revealed evidence of cannibalism during the Greely Expedition to Lady Franklin Bay (1881-1884).

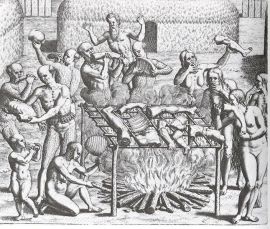

Of all of the behaviors associated with savagery in the 19th century, none carried the same freight as cannibalism. Since Columbus returned to Europe in 1493 with reports about the man-eating propensities of the Caribes, Europeans viewed cannibalism as a marker of human societies at the lowest rung of civilization. (Even the name cannibalism is indelibly tied to the native peoples of the Americas since it derives from “Canibes,” a variant of Caribes, which is the etymological root of Caribbean).

When Abraham Ortelius published the world’s first commerical atlas in 1580, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theater of the World), he included a frontispiece with goddesses for each of the known continents. As Europe sits preeminant at the top of the columns, flanked by the “semi-civilized” societies of Asia and Africa, America reclines naked at the bottom, holding an arrow and cradling a human head.

Frontispiece, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, Abraham Ortelius, 1580

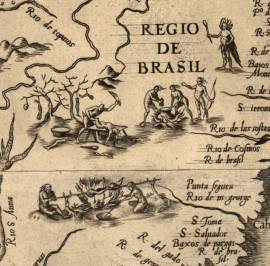

Maps of the New World showed figures of cannibals with the frequency of mountains and palm trees, even though few of these scenes were based upon eyewitness reports.

Cannibals, detail of Diego Gutiérrez, Americae sive qvarta e orbis parties nova et exactissima description, 1562

Cannibals in Brazil, Hans Staden, 1557

Cannibalism gave New World narratives of exploration a bit of spice. But more importantly, it confirmed an idea that was already widespread: that Europeans existed on a different level of civilization and that the occasional injustices of European colonization still represented a step forward for the “savage peoples” of the Americas.

As the 19th century witnessed an increasing number of accounts of white explorers caught eating their own kind, the dissonance was sometimes too much. Dickens remains convinced that Franklin’s men had fallen prey to some other fate. And as for the decimated, half-eaten corpses of the Greely Expedition? After quick discussion with the Secretary of the Navy, Greely informed the press that the bodies had been used as “bait” for capturing shrimp.

This and That

Beware of Hartford, place of pestilence. Flu has moved through my campus like a gasoline fire, with over 100 students out of class. At the same time, a weird and malevolent norovirus is moving through the Hartford public school system, cleaning out classrooms while janitors run screaming. If this wasn’t enough, my son’s daycare was almost empty yesterday because he, along with half of his classmates, came down with conjunctivitis (the rest were out with stomach flu). I call myself lucky. Feverish, brain stuffed with cotton, I’ve made it through with a maniacal head-cold.

No heavy thoughts today, then, just some places to visit:

Interdisciplinarity is a term that gets approving nods from most academics. We should all work together! But it usually ends here. On the table of academic bounty, interdisciplinarity is the curly parsley: lovely to look at, but no one ever eats it.

Yet Andrew Stuhl’s interesting post on interdisciplinarity lays out some of the efforts being made across the disciplines. Maybe there is reason to hope.

The Arctic Blue Books Online represents a massive trove of British reports on Arctic expeditions in the 19th century. Cataloged with care and prodigious effort by Andrew Taylor, the 6000+ pages of the Blue Books are now available online along with Taylor’s helpful indexes and finding aids. Where else can one find index references to “Cannibalism” and “Calves Foot Jelly” in the same place?

Finally, Peter Etnoyer of Deep Sea News tells us that the narrative and scientific reports of Challenger Expedition (1872-76), a stunningly ambitious attempt to sound, trawl, fish, and net a new science of the sea, are currently online (along with lovely image scans) here.

This week we remember British explorer Charles Darwin who turns 200 on Thursday. For those living close by, I’ll be giving a lecture tonight at U Conn-Avery Point on Darwin in the Age of Exploration (Branford House). Good pictures and free coffee to those who attend.

Call Me Starbuck

Guy Waterman

On February 6 2000, Guy Waterman drove his Subaru Impreza to Franconia Notch in New Hampshire, hiked up Mt Lafayette, and in the windy -16 degree night, let himself die of exposure.

Waterman was a man of many gifts and torments, a climber, writer, and environmentalist who lived for thirty years with his wife Laura Waterman off-the-grid in Vermont.

Of these torments, which drove him into deeper and deeper isolation, Waterman said little. Yet he wrote about them through the characters of literature. He was Shakespeare’s Ariel battling the witch-child Caliban. He was Milton’s proud Satan. He was tragic Prometheus. He was Melville’s Ahab.

Prosper and Ariel, William Hamilton, 1797

Ahab. As I read Laura Waterman’s spare, graceful memoir, Losing the Garden: The Story of a Marriage , it seemed an appropriate metaphor for Guy Waterman.

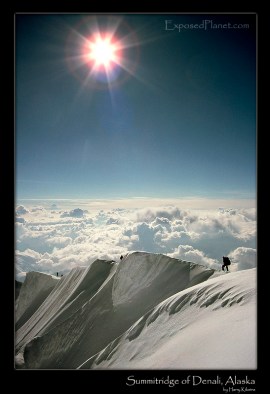

Then, this morning, reading Maria Coffey’s book, Where the Mountain Casts its Shadow: The Dark Side of Extreme Adventure, Ahab surfaced once again. Near the summit of Everest in 1996, David Breashears and Ed Viesturs come across a body near the Hillary Step.

They found [Bruce] Herrod’s body clipped on to fixed ropes with a figure-eight rappel breake. He was hanging upside down, his arms dangling, his mouth open, and his skin black. “Like Captain Ahab,” Breashears later wrote, “lashed to his white whale.” [Coffey, 118]

It made me pause. One hears different many different literary metaphors for explorers and adventurers, but rarely Ahab.

Successful explorers find comparison to Odysseus, the brilliant, cock-sure hero of Homer’s Odyssey. (Confined to the scurvy-ridden cabin of Advance over the long winter of 1854, Arctic explorer Elisha Kane would keep up the spirits of his men by reading them Alfred Tennyson’s Odyssean poem “Ulysses”) Those explorers who perish are commonly portrayed as Icarus, a boy whose joy with altitude overcame good judgment, causing him to fall to earth.

Both of these are figures are imperfect but bright of heart. Ahab is a different creature, a man of darker spirit, a figure turned in upon himself. Ahab’s travels to the ends of the earth bring no discovery or enlightenment; he sees only the white whale. Ultimately his obsession brings tragedy to all, not only Ahab, but to those who follow him.

Is Ahab the true spirit of extreme adventure? You would not think so reading most adventure literature. While these books reveal some of the dirty laundry of expeditionary life, they mostly chronicle struggle and attainment, heroism and transcendence. Indeed, elite climbers often speak of the transcendent moment as the Holy Grail of high-altitude climbing, that thing which brings them back, time and time again, to the most dangerous mountains in the world.

Yet transcendence, going beyond oneself, is the opposite of obsession, a psychic tunneling-in so extreme that it diminishes or excludes everything around it: Golem’s ring, Ahab’s whale, Herrod’s mountain.

Grim metaphors indeed. Perhaps the legions of 8000-meter peak baggers and Seven-Summiters should read Moby-Dick, digest the moral of Ahab, and then turn their attention to the Ahab’s Quaker First Mate Starbuck:

[H]is far-away domestic memories of his young Cape wife and child, tend[ed] to bend him … from the original ruggedness of his nature, and open him still further to those latent influences which, in some honest-hearted men, restrain the gush of dare-devil daring, so often evinced by others in the more perilous vicissitudes of the fishery. “I will have no man in my boat,” said Starbuck, “who is not afraid of a whale.” By this, he seemed to mean, not only that the most reliable and useful courage was that which arises from the fair estimation of the encountered peril, but that an utterly fearless man is a far more dangerous comrade than a coward. [Melville, Moby-Dick]

If this seems too tame or Quakerish for the modern climber, perhaps they’d learn more from a more modern Starbuck, the character Kara “Starbuck” Thrace of the Sci-Fi channel’s Battlestar Gallactica. Thrace is a woman of many demons, of violent appetites. Her thirst for transcendent experience has no limits. But ultimately she channels her dare-devilry into objects of common interest, the search for Earth, the return home.

Kara "Starbuck" Thrace (Katee Sackhoff) of Battlestar Galactica

Maybe I Was Wrong

Why do people climb 8000-meter mountains? Free-solo the Eiger? BASE jump the Eiffel Tower? Motives are tricky things.

My work on Arctic explorers gave me a way to think about it.

Nineteenth-century explorers had their own answers to the “why” question. In the 1850s, when U.S. exploration of the Arctic began, explorers defended their missions by describing all of the commercial benefits that would accrue from their expeditions: new routes to Asia, new whale fisheries, new technological innovations in ship design. (Interestingly, NASA features a similar-sounding set of commercial benefits when it justifies its current plan to return humans to the Moon and Mars).

Then, in the 1880s, explorers changed course, justifying their exploits by anti-commercial motives: we explore because it is impractical. We explore to escape the strictures of the civilized world. We explore for the sake of exploring. Or, in George Mallory’s translation for mountain climbing, “because it’s there.”

George Mallory

In the language of day, the explorer had succumbed to “Arctic fever,” a term used over and over again in the last decades of the nineteenth century to describe the seemingly irrational behavior of explorers in putting themselves at risk:

“The northern bacilli were in my system, the arctic fever in my veins, never to be eradicated.” Robert Peary, 1898

“The polar virus was in [my husband’s] blood and would not let him rest.” Emma DeLong, 1884

Explorers are ” infected with the same spirit.” Frederick Cook, undated

“Arctic enthusiasm is an intermittent fever, returning in almost epidemic form after intervals of normal indifference.” McClure’s Magazine, 1893

As I tried to make sense of “Arctic Fever” for my book Coldest Crucible, I concluded that all of this talk of fevers was just another means to show purity of motive:

The disease may seem to be nothing but a playful literary metaphor, but it had serious functions. Arctic fever located the urge to explore in the human passions. It was a condition that afflicted the heart against the better judgement of the mind, operating beyond conscious control. Why should anyone attempt to reach the North Pole when it served no useful or scientific function? Because -explorers claimed- they felt irrationally compelled. In this way, Arctic fever masked rational motives for voyaging north, namely, the promise of celebrity and financial reward.

While explorers spoke about their irresistible compulsions, they were simultaneously working out huge publishing contracts, product endorsements, and lecture fees. At the time I wrote my book, it seemed to me that all of this talk of instinct, true spirit, experience of the sublime, etc. was just a matter of bait-and-switch: finding motives that would impress paying audiences and would hide the true, mercenary motives behind them.

I haven’t abandoned this line of thinking entirely, but after reading the first chapter in Maria Coffey’s book, Where the Mountain Cast Its Shadow, I think I need to revise it.

Coffey’s book is about the effects of extreme adventure on the people left behind: spouses, parents, and children who have to come to terms with the loss of loved ones. She starts her book with interviews of adventurers who talk about their motives in putting themselves at such risk.

“Endurance, fear, suffering cold, and the state between survival and death are such strong experiences that we want them again and again. We become addicted. Strangely, we strive to come back safely; and being back, we seek to return, once more to danger.” Reinhold Messner

“I was totally possessed. The experience was like some inner explosion. I knew it would somehow mark the rest of my life.” Wanda Rutkiewicz

Coffey’s list of climbers who speak about this compulsion is impressive. It extends beyond the elite, celebrity climbers such as Messner and Rutkiewicz to include those who do not have agents, publishing contracts, or product endorsements.

I am realizing that it’s not enough to label this exploration “fever” as merely a savvy form of marketing. It is clearly a psychological manifestation too, one that Coffey links to the impact of extreme risk on biological factors such as adrenaline and dopamine.

Coffey also describes the way that such extreme experience can have, ironically, a quieting effect on adventurists, making them feel less moody, more even-keeled, more able to focus on the present moment. Indeed, more than one climber described climbing as an escape from distraction, a way to concentrate on the task at hand, to live in the moment, to experience things more fully.

At times, it made me wonder if there a common psychological profile for elite climbers. The frequency of people referring to attention and distraction sounded very similar to interviews conducted by Dr. Edward Hallowell in his book, Driven to Distraction, a book about attention deficit disorder (ADD).

The point here is not to throw out one label in order to replace it with another. But Coffey’s book is making me realize that my work on the history of exploration should not only play out at the level of nations, empires, commerce, and popular culture. I need to make room for the individual, a tangled world of emotion, experience, and behavior.

I know that many of you are thinking “No duh! This is standard stuff for climbing books.” True enough: Will power, spirit, fear, endurance, ecstasy: the meat and potatoes of adventure literature. But cultural historians are trained to think of personal motives as ultimately unknowable, a black box that should not be opened. To psychoanalyze the historical subject is like touching the third rail in the subway. Dangerous terrain.

The Search for Authentic Experience

It’s raining deadlines here in Hartford: grant proposals, course proposals, exhibition labels, article drafts, etc. All of it due this week or next. On top of it all, tomorrow’s the first day of classes. Time to polish up the syllabus, de-lint the sweater, iron the button-downs.

I just submitted a proposal to teach an honors course here (see below). The course grows out of my work in the history of exploration. I would love your feedback about the topic, how you think it coheres (or digresses), readings that you think improve the course, areas unexplored or under-explored in the syllabus.

HONB 110: The Search for Authentic Experience

Philip K. Dick

Course Description

Science fiction writer Philip K. Dick once said that all of his writings circled around two questions: “what is real?” and “what is human?” Dick’s questions extend beyond science fiction. Indeed, they traverse the scale of human history. If we traveled back in time to the fifth century BCE and asked Plato what sorts of things were on his mind, I suspect he would tell us much the same thing as Dick. Where does one look for the true reality of the world? And once located, how does one reach it?

These are the questions that structure HONB 110: The Search for Authentic Experience, a course that examines the long quest to discover what’s real and the processes by which people try to attain it. Questions of truth usually reside in the domain of philosophy, and debates about “what is real” could easily fit within an epistemology course from Parmenides to Karl Popper. Yet the point of Authentic Experience is to show how such lofty, stratospheric ideas play out on the muddy terrain of human culture. After all, it is not some esoteric exercise in metaphysics that inspires people to search for what’s real: it’s because people sense, in a deeply personal way, that what they experience is not real enough.

For example, Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, which students read during the first week of the course, can be viewed as a purely metaphysical parable in which a prisoner comes to realize that his life in the shadows of a cave is a poor imitation of the reality of the world above. Yet Plato’s allegory is not merely a thought experiment. It is also a specific critique of life in Athens, a society that feared the ideas of Socrates enough to make him a prisoner, eventually executing him.

St. Francis of Assisi, Anthony Van Dyck, 1627

This dance between philosophical ideas and specific cultural concerns frames the first five weeks of Authentic Experience. In particular, this section of the course examines the issue of worldliness and asceticism across cultures. Material luxuries — silks, spices, opium – have long been seen as enhancements to sense experience. Moreover, they have often served as a measuring stick of refinement and cultural progress. Yet others have seen them in darker terms, as distractions, leading people off the narrow path of enlightenment. Do such luxuries enhance our lives as Democritus and the Epicureans argue? Or are they the subtle gloss that separates us from the vibrancy of raw experience as St Francis of Assisi and Siddhārtha Gautama warn us?

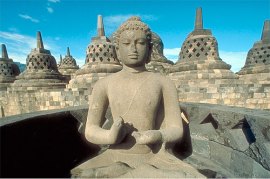

Buddha statue in Borobudur Stupa, Java, Indonesia

The second section of the course takes up “the journey” in the pursuit of authentic experience. In his book on comparative mythology The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell identifies the quest as a key component in hero stories across cultures, including those of Gilgamesh, Odysseus, Osiris, Moses, Budda, and Christ. Campbell noted that heroes prove themselves not simply by achieving their goals at the end of the quest, but by undergoing a transformation during the quest itself. The arduous journey is not merely the literary prop of myths and legends. It is a part of the real world, having been adopted by many cultures as a means of purification and enlightenment. In addition to reading excerpts from Gilgamesh, the Odyssey, the Bible, students will also read about ritualized journeys such as Christian pilgrimages and the Muslim Hajj.

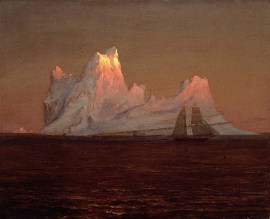

Scene of icebergs, Frederic Church

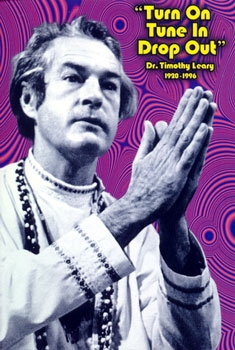

The final section of the course looks at the search for authentic experience in the modern world, starting with 19th century Romantics who sought to move beyond the boundaries of empirical reason to achieve an experience of the sublime. Students will examine the landscapes of Frederic Church and his contemporaries, artists who traveled to the wild places of the world in hopes that it would get under their skin, alter their perceptions, and infuse their works with something unique. Finally, the course will consider twentieth-century quests for the real, such as the counter-cultural movement of the 1960s which sought self-actualization through music and hallucinogenic drugs. It will end by examining the current “Age of Adventurism” in which trekkers, climbers, and jumpers attempt increasingly risky, death-defying feats as the means for escaping the quotidian drudgeries of modern life.

Timothy Leary

The course will include two field trips: to the Wadsworth Athenaeum to view the collection of Hudson River School landscapes, and to Mt. Monadnock in Southern New Hampshire for a day-hike to the summit. It will also feature guest lectures by Steph Davis, elite climber and author of High Infatuation: A Climber’s Guide to Love and Gravity, as well as local scholars Heidi Gehman of the Hartford Seminary and Bill Major of Hillyer College.