Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationThe Forging of Races

I’m not in favor of ducking debates, but in matters of science and religion, it’s best to keep one’s head down. Not that I mind giving and taking a few hits, but the slings and arrows hurled by various bloggers are not easily deflected by reason. Much of the time, arguments on both sides seem to proceed without any sense of historical nuance.

For example, creationists often speak about science as if they were playing billiards: science is a game of facts, observable, measurable, linked together by visible and predictable causes. Any forces that take place off the felt table (such as phenomena of the far away or the deep past) fall into the zone of “theory,” a pejorative term that comes to mean speculation or opinion. This works well with pool, but hardly science, where strict empiricism or “Baconian science” has been out of vogue since the 18th century.

On the other side, the polemical evolutionists tend to lump anti-evolutionary arguments together under the category of “anti-science.” This would have been news to nineteenth-century scientists such as Richard Owen and Georges Cuvier, both of whom advanced serious objections to evolution on scientific, not religious, grounds.

Richard Owen

I bring these issues up not because I have picked up my sword and plan to fight the good fight, but because I’m reading an excellent book on science and religion by Colin Kidd called The Forging of Races: Race and Scripture in the Protestant Atlantic World, 1600-2000.

Kidd argues that scriptures are largely color-blind, agnostic on the question of racial hierarchies. Yet he also argues that the Bible became the guide for western scholars trying to understand the origins of human races.

It is one of the central arguments of this book that, although many social and cultural factors have contributed significantly to western constructions of race, scripture has been for much of the early modern and modern eras the primary cultural influence on the forging of races. [Kidd, 19]

Even more interesting, Kidd argues that scriptures held racism or “racial essentialism” in check for much of modern history. As much as one can see rampent racism in the development of the Atlantic slave trade (pioneered by Christians and other followers of the Book), Europeans and Euro-Americans usually reaffirmed the common humanity of the races as “Children of Adam.” To do otherwise was to exclude some races from the original sin (and the promise of salvation) which emerges out of Genesis.

By the nineteenth century, certain scholars advanced the theory that non-white races were “Pre-Adamites,” humans who were formed by God in a separate act of creation. As religious theories of racial origin gave way to increasingly secular explanations, racial thinking became even more extreme, leading to policies of racial social control, eugenics, and genocide.

In short, the Bible was — unintentionally perhaps — a bulwark against the most extreme ideas of racial theory. If it promoted ideas of racial origin which now seem naive and far-fetched, it also protected the Atlantic World from some of the full blown horrors of racism realized during the more “scientific” age of the twentieth century.

New Arctic Exhibition

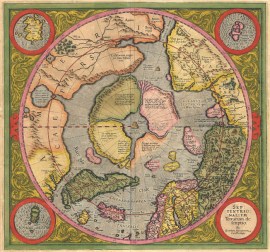

Septentrionalium Terrarum Descriptio, Gerard Mercator, 1611. A polar projection showing islands and open water at the North Pole.

Apologies for the spare postings over the last two weeks. I’ve been doing a lot of out of town projects. Last week I was down in DC where Story House Productions is putting together a documentary on the Cook-Peary North Pole Controversy of 1909. They interviewed me in the historical newspaper room of the Newseum (just off the National Mall). Museums are strange places anyway, but after dark they become positively surreal.

News History Gallery, Newseum, Washington DC.

I was also up in Maine working out the kinks of an exhibition I am curating at the Portland Museum of Art called “The Coldest Crucible: Arctic Exploration in American Culture.” The show examines many of the same themes as my book (no surprise). But where my book was limited to 18 black-and-white prints, the exhibition delivers a much broader range of paintings, photos, and illustrations. The point is to show how the Arctic of these images represents a hybrid-world: a vision of polar regions, colored by the aesthetics and preoccupations of the Americans who traveled there.

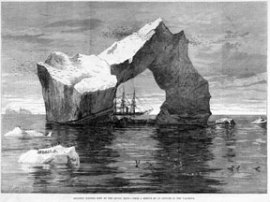

Gigantic Iceberg Seen By the Arctic Ships, From a Sketch by an Officer of the Valorous, Illustrated London News, 1875

You can see some of the images of the show here.

I gave an interview about the exhibition on Channel 6 while I was there.

The show opens this Saturday and runs through 21 June.

Interview with Steph Davis

Davis on El Capitan

Steph Davis climbs such outrageously steep things that one wonders whether sorcery is involved, that perhaps her gifts extend beyond climbing to include the manipulation of physics. She has put up first ascents on the world’s most frightening big-walls, from mountains in Pakistan and Baffin Island to Kyrgyzstan.

Davis is the first woman to free climb the Salathe Wall on El Capitan in Yosemite and to summit Torre Egger in Patagonia. She has also become an expert in BASE jumping (the acronym stands for Building, Antenna, Span, and Earth), a wild and unforgiving off-shoot of skydiving.

Yet Davis is also a scholar and accomplished writer. Her masters degree in literature focused on the canon of mountaineering literature. In her book, High Infatuation, Davis asks difficult questions about high-risk climbing, examining her own motives, personal relationships, and the broader meanings of her life’s work.

Mt Fitzroy, Patagonia

Welcome Steph Davis.

You’ve done some amazingly dangerous climbs, from Mt Fitztroy in Patagonia to the Salathe Wall on El Capitan. When you pursue projects like these, how do think through the risks? Is there a red line that you won’t cross? Or does the line change as you climb?

Climbing varies a lot with risk. For example, free climbing el cap is really difficult, but is much less risky than climbing in the mountains, even if the peak is technically easier to climb. So every style of climbing presents different challenges, in terms of difficult and danger, with lots of blurred lines too. I feel very aware of those elements, and at times I am pulled more towards pushing difficulty, and at other times more pulled toward negotiating risk.

For your masters thesis at Colorado State University, you studied mountaineering literature. Could you talk a bit about your project?

I was in the literature graduate program at CSU, and when the time came to do a master’s project, I tried to think of areas that would interest me. Finally I went to my committee and asked them if I could do the project on mountaineering literature. At the time, this didn’t exist as a field of study there. They were really receptive, and told me if I could write up a bibliography of works with short descriptions as part of the project, they would accept it. I chose a selection of mountaineering and climbing books I found canonical and made the bibliography, and then wrote a thesis project called “the reality of experience in mountaineering literature,” about the ways in which reality can be so disparate and shifting for each individual who is living through extreme experiences. I framed the project as a personal essay, around a summer spent climbing on the Longs Peak Diamond in Colorado, because that was a writing style I was studying a lot.

Do you identify with any particular explorer or mountaineer?

I will always be in awe of Ernest Shackleton, and what he accomplished.

When Darwin went to Patagonia, he carried a copy of Alexander von Humboldt’s Personal Narrative with him, an account of Humboldt’s own journeys through South America. Do you bring books with you on your climbs? Do you ever have other climbers’ experiences in mind as you make your ascent?

When I go on an expedition, I choose carefully since weight allowances force me to limit the books I bring, and I read very fast. So it‘s impossible to bring enough books for a whole trip. I usually try to bring some very thick, dense novels, also some books about natural science. I also bring one or two books in French or Spanish with a dictionary, because those can be entertaining for days. On actual climbs, I can barely spare the weight to bring food, much less books….but if I am climbing big wall style, I will always bring a journal.

You’ve written about the challenges of being a woman rock-climber in a male-dominated sport. Male climbers didn’t always take you seriously or belittled your accomplishments. Has that changed with your success as a climber or do you still feel like you are treated differently?

It has changed. I wrote about that phase in my book, because it was a strange experience for me. As time has gone by, that phase is over, and I’m relieved, because I didn’t appreciate it.

Do you think being a elite women climber affects the way you are treated by sponsors, fans, or the general public?

That is hard for me to answer. I have been climbing for 18 years, half my life, and have been climbing at a high level for a long time. So I don’t have much perspective versus not being that way. People I meet do tell me that they are inspired or motivated by things I’ve done, and that makes me feel good. But I also feel that doing all these things is not really so unique or special. Everyone I meet has done amazing things in life, they just might not have the same sense of drama attached.

Many people can identify with your struggle to balance family relationships with your work. Yet even by these standards, it seems that you spend a great deal of time away from your friends, family, and dog Fletcher. How do you find the balance point in your life between climbing and these relationships?

Living a simple life is really difficult sometimes, oddly enough. For me, the hardest challenge right now is balancing travel with climbing. Travel is about the worst thing I can do for climbing fitness, but sometimes it‘s necessary for work or certain climbing or jumping plans. When I am at home, on a schedule of working out, and living a simple life, I can climb my best. Being in cars and airplanes and not climbing regularly just doesn’t work….so it can be tricky. In recent years I started base jumping and wing suit flying. Now when I am traveling a lot, I take advantage of being in good jumping places, and focus on jumping instead. Which is great. It is also interesting right now, with Fletcher being 15 and very arthritic. She does not travel well, and mostly needs to be at home where she is comfortable since she can’t walk as well. I definitely prefer to do things which don’t require a lot of walking (certain climbing areas with short approaches where I can carry her and good campsites, skydiving at the local airport where she can be at the landing field, base jumps where she can hang out at the landing site) right now. I sometimes have to force myself to go running, because I really miss her when I run. And I worry a lot when I go on a trip for several weeks, right now.

After successfully free-climbing the Salathe Wall, you experienced a period of depression and self-doubt. As I understand it, you were trying to reconcile your beliefs in a philosophy of acceptance and mindfulness with the sometimes obsessive, single-focused determination you needed as a climber to reach your goals. Could you speak a bit about this? Does this conflict still affect you or have you come to terms with it?

The Salathe experience was pretty severe for me, partly because the climb took so much out of me. I was also dealing with a lot of challenges in my marriage, which made things even harder and raised a lot of questions about partnership, support, and giving. So the experience forced me into a lot of self-examination, and also eventually led me to conclude that there are positive ways to organize personal projects, without having to feel like a burden on others. So I feel very happy now when I get enthusiastic about a project, because I have found there are fun ways to involve others, without the sense of imbalanced giving or taking which is so often the characteristic of a major, individual climbing project, and that makes the entire experience very fulfilling.

Davis on the Salathe Wall, El Capitan, Yosemite

It seems to me that the conflict you experienced after climbing the Salathe has parallels in the climbing community where some climbers seek some kind of inner peace or connection with nature whereas others are interested in peak-bagging and new ascents. Could you speak a bit about the culture of elite climbers? Is there a common set of values or is everyone different?

One of the best things about climbing is the fact that people can experience it in so many different ways.

What is your next big project?

Something involving free soloing!

Thanks Steph, good luck and safe travels.

For more on Davis’s writings and climbing career, visit High Infatuation and read my earlier post Lessons of the Free Solo.

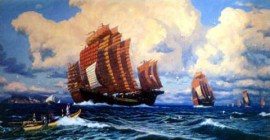

Asia on Top

Zheng He's fleet sailing the Western (Indian) Ocean, 1405-1433. 20th century painting, artist unknown.

Exploration seems an inclusive concept, a big-tent activity that admits anyone with a geographical goal and a good pair of shoes. But like most terms, exploration has hidden meanings and rules, ones that restrict certain places, people, and activities.

For example, Americans have made a national mythology out of exploration, creating a genealogy of pioneers and explorers that extends from Lewis and Clark in 1804 to Neil Armstrong in 1969. Were extraterrestrials listening in to the speeches of the 2008 Democratic National Convention, they would be forgiven for thinking that Americans single-handedly discovered the world. (For more on exploration talk at the DNC, read this)

Yet even the most blinkered American manifest-destinorians would have to extend the “spirit of exploration” to Europeans. Otherwise they would have to exclude the Renaissance all-stars of exploration, Christopher Columbus, Vasco da Gama, and Ferdinand Magellan, from their ranks.

Protestant Americans wrestled with exactly this issue in the 19th century, ultimately deciding to embrace southern European explorers as a part of their own cultural heritage. In their favor, Columbus and his successors were white Christians, even if they suffered from being papists, speaking Spanish and Italian, and drinking wine on Sundays.

Columbian Exposition Commemorative Half Dollar, 1892

But this is about as inclusive as Americans have been willing to get. Expeditionary activities of African and Asian nations are duly reported of course. Western press agencies keep us apprised of the South African National Antartic Programme (SANAP) and the Chinese Shenzhou Space Program. But one detects in western press coverage a view that these accomplishments are adaptations to a Western philosophy of discovery, a mimetic activity rather than something which expresses core features of Asian or African culture.

Put differently, exploration has become the symbolic equivalent of baseball, an activity played all over the world, but still seen in the U.S. — now and forever more — as an archetypally American game (debts to cricket aside).

Were we to sit down with early European navigators in the 15th century, I think they would be astonished by all of this Euro-American strutting and preening. After all, exploration took off in Europe because Europeans felt they were being pushed off the stage of world events.

Despite the pageantry of statues and paintings, the European Age of Discovery was less about curiosity than fear and admiration, an appreciation for non-European powers, particularly in Asia, that held the keys to European collapse or prosperity.

For medieval Europeans, the Orient was the center of the world. It was the font of Judeo-Christian religious history, the site of the Holy Land. It was the center of global commerce and trade, particularly luxury items. While Frankish farmers ate mutton and plowed their fields in scratchy woolens, Marco Polo enchanted readers with stories of silks, teas, and concubines from Cathay.

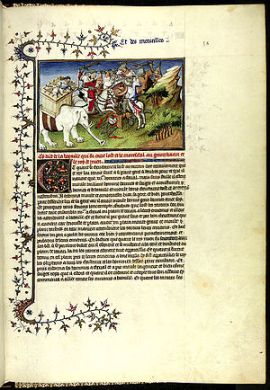

Travels of Marco Polo, manuscript page, 1298

Meanwhile Crusaders brought back cinnamon and clove from the Spice Islands and cottons from India. As for geopolitical power, any Pole, Serb, or Castilian from the late Medieval period would have stories to tell about the powerful pagans of the East. One forgets that before the centuries of European hegemony, European border kingdoms were continually reacting to events from empires East: Mongols, Persians, and Ottomans.

Evidence for this comes from many sources. The importance of the East is pounded into the English language of geography. For example, the word for Eastern lands “Orient” (Chaucer, 1375 CE) soon begot words of directionality such as “orientality” (Browne, 1647 CE) and “to orient” (Chambers, 1728 CE).

Moreover, European cartography expressed a Eastern-centric vision of the world. European T-O maps produced in late medieval Europe usually faced East and centered on Jerusalem. It was common for such maps to also overlay important religious symbols such as the body of Christ or the sons of Noah on the world’s continents.

T-O map from the Etymologiae of Isidorus, 1472. Asia is on top, Europe is bottom left, Africa is bottom right. The names of Noah's sons are placed under each continent.

Mappa Mundi showing Noah's ark and three sons on three continents in La Fleur des Histoires, Valenciennes, 1459-63

European conquests in Asia and America in the early 16th century did much to boost European self confidence. (See for example, Abraham Ortelius’s frontispiece for his 1580 Atlas in my post on cannibalism)

There is much more to be said about Asia in the history of exploration, particularly 19th century conceptions of the East and Edward Said’s influential work Orientalism. All of that will have to wait for another post though. For now, here are a few links on history, travel, and exploration in Asia:

The Silkroad Foundation “The Bridge Between Eastern and Western Cultures”

The Athena Review Journal of Archeology, History, and Exploration

Astene Association for the Study of Travel in Egypt and the Near East

The F-Word

The word “Frontier” lives a double-life. In the public world of bookstores and Star Trek episodes, it carries itself with bearing, symbolizing something wild and lawless, a place of promise, adventure, and renewal. Within the Academy, however, “frontier” carries the whiff of the disreputable, a word that has fallen into disuse. Once praised and powerful, it now stoops on stair-landings to rest.

The decline of the “frontier” within the Academy has been long and precipitous. Made famous by Frederick Jackson Turner’s 1893 essay “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” it’s been the inspiration of dozens of books and hundreds of articles.

Frederick Jackson Turner

Why? Because Turner linked the frontier to the story of American progress, arguing that it rejuvenated American culture by placing pioneers into contact with the wild, savage world at the edges of civilization. In the process, pioneers had to break from the strictures of the civilization they left behind and re-imagine life from the ground up. In the process, Turner argued, they recapitulated the long arc of human society from savagery to civilization, infusing American society with the energy of their innovations.

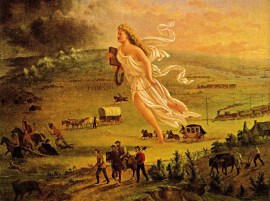

American Progress, John Gast, 1872

The frontier thesis was (and in some quarters, still is) seen as a compelling story of American uniqueness. In it, supporters found a story to justify a view of Americans as a special, exceptional people.

Still, the frontier thesis found itself under attack from many quarters. In the 1980s, New Western Historians argued that the frontier thesis did not accurately present the progression of changes in the West, nor did it explain the broader arc of American progress. Moreover, frontier was a word that privileged one perspective in the story of the West: the pioneers who viewed these lands as wild and savage rather than the indigenous peoples who called them home.

Between those supporting the thesis and those criticizing it, discussion of the Frontier Thesis seemed to be everywhere, a subject so fecund that it threatened to overwhelm all other subjects within the discipline. All of this ultimately led historian Patricia Limerick to label “frontier” as the F-Word, a term that had become a hindrance, rather than a help, to historian scholarship.

Patricia Limerick

What to do? In her 1992 book Imperial Eyes, Mary Louise Pratt abandoned the term frontier, replacing it instead with the phrase “contact zone,” a less loaded term for the place of encounters between indigenous peoples and Euro-Americans.

I see the wisdom in Limerick and Pratt’s decisions. And yet still, I think there’s still a place for frontier, particularly within the field of the history of exploration. Limerick is right to argue that frontier is a loaded term, one that brings with it a particular tilt. It shares this ground with other loaded terms such as “discovery” and “exploration,” concepts which only make sense from the perspective travelers rather than natives.

Joseph Banks

Yet by definition, stories of exploration adopt the perspective of people traveling into the field. For expeditionary scientists — such as Alexander von Humboldt, Joseph Banks, Charles Darwin, and Alfred Russell Wallace — the grand stage of global travel did represent frontiers, places of profound mystery, inspiration, and otherness.

That their perspective represented a limited frame of reference is clear. Still, within this frame of reference, we see powerful transformations of thought and identity. Expeditionary letters and field sketches express the weight of these events, the frontiers of new experience.