Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationOn Biography

Every year, history conferences feature panels about biography. These are not talks which offer a biography in the manner of A & E’s Biography Channel (which profiles Kirstie Alley tonight) but ones that consider biography as a genre. They come with titles like “Making a Case for Biography: New Methods in the History of X.”

Why do professional historians feel the need to defend biographies? They have never stopped writing them. Academic presses remain eager to publish them. Yet biography still carries a reputation of being popular at the expense of being deep, of being an intellectual lightweight in a world of hipper, higher-powered genres: micro-histories, cultural histories, comparative histories, and transnational histories. In the high-cultural universe of academic writing, biography is Gilligan’s Island.

There are many reasons for this, but one key reason is structure. Biography focuses on the role of individuals in shaping events. As such, it sails against the wind of modern scholarship which, for forty years or so, has located historical change in institutions, corporations, governments, and national cultures. And individuals? Go to Barnes and Nobles.

Moreover, biography is tricky as a genre because it sometimes lures historians into thinking that they are really psychoanalysts, that they can interpret the thoughts and feelings of their subjects. If Freud couldn’t ferret out the real causes of his patients’ behavior, why do we think biographers will prove any better at it with people who are dead?

Sigmund Freud's Couch

That said, I like biographies. If the genre has limitations, it also has spirit. Whether or not people offer a useful way to look at historical change, they are interesting to read about. And the way biographers choose to tell the stories of individuals is interesting too.

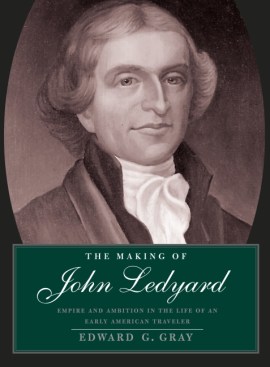

For example, Ed Gray’s biography of John Ledyard (which I reviewed here) gives a rich account of Ledyard’s travels. Yet Gray avoids the temptation to put him on the couch and Ledyard remains a mysterious figure, a shadow in the foreground of a brightly painted world.

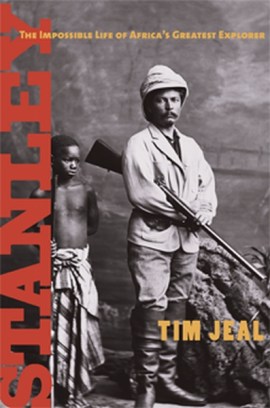

By contrast, Tim Jeal is far freer with his psychological analysis of Henry Morton Stanley. This should probably make me uneasy. But Jeal builds his psychological hypothesizing on a solid foundation of evidence. He has done his homework on Stanley, a man who left an Africa-sized archive of primary source material.

Better yet, Jeal uses his analysis of Stanley to say interesting things. For example, he observes that Stanley inflated the number of Africans that he killed from the island of Bumbireh in Lake Victoria, a strange boast given that it contributed to Stanley’s reputation as a cold-hearted killer.

Yet Jeal argues that Stanley’s actions make sense only if one understands his shame at being humiliated by the leader of Bumbireh weeks earlier, something that Stanley — abandoned by his parents and raised in a workhouse — was keenly sensitive to. Moreover, Jeal argues that Stanley misjudged his audience’s reaction to the Bumbireh story, thinking that Europeans and Americans would like stories of warfare in Africa, much as they liked “big kill” stories about the Indian wars of the American West.

Despite their very different styles, I recommend both books.

The Explorer Gene

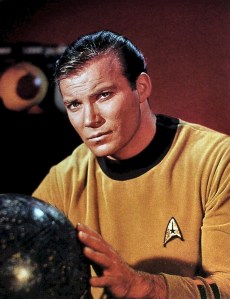

In 1987, Dr. C. Robert Cloninger created the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire (TPQ). Despite its unique, Star-Trekian name, Cloninger’s TPQ entered a crowded field of personality tests, such as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), the Enneagram, and the Oxford Capacity Analysis (OCA).

Spock administers the TPQ to Captain Kirk

The TPQ distinguished itself in two respects.

First, it came from a trusted source within the medical establishment. Cloninger, a medical doctor and professor of psychology at Washington University in St. Louis, developed the TPQ from clinical research.

Second, Cloninger’s test made claims about the genetic origin of behavioral differences. Specifically, it argued that important aspects of personality are heritable, that our temperament grows out of genetic factors as much environmental ones.

As Cloninger sees it, the route from gene to expressed behavior follows a path laid down by neurotransmitters, particularly seritonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. The three dimensions of the TPQ (which measure harm avoidance, reward dependency, and novelty seeking) correspond to different sensitivities in these three neurotransmitters.

Cloninger’s TPQ, now somewhat modified, remains controversial within the field of psychology. Some studies confirm a link between personality assessment and neurotransmitter sensitivity while others do not. In 1996, two studies in the United States and Israel found a correlation between a high proclivity for novelty seeking and a longer sequence in the D4 dopamine receptor gene.

Scientists hypothesized that the added length of the D4Dr sequence made certain individuals particularly sensitive to changes in dopamine. High levels of dopamine — secreted in moments of pain, pleasure, or excitement — would lead to an intense high. By contrast, moderate levels of dopamine would leave the long D4Dr individual feeling depressed.

Novelty seeking, then, was not simply an acting out against one’s parents or the product of a mid-life crisis. It was long-D4Dr individuals’ attempts to self-medicate: to BASE jump, drag race, and free climb their way to their next rush of dopamine.

The discovery of the long D4Dr gene in 1996 captured popular attention. Was exploratory behavior more a matter of genes than life experience? Did Lord Byron chase maids and attack Turks because of a mutation on his 11th chromosome? Was Columbus’s discovery of America an elaborate attempt to get high?

Such genetic arguments are simplistic. Recent studies have brought the TPQ test and the D4Dr-novelty seeking link into question. Moreover, as Maria Coffey points out in her book, Explorers of the Infinite, many of the riskiest activities — such as high altitude mountain climbing – come with long periods of drudgery. If high-risk activity is the key to unlocking an individual’s neuro-chemical Valhalla, the long D4Dr adventurer would do better working as a day-trader on Wall Street or playing the $500 tables in Atlantic City.

What’s more interesting to me is idea that “exploratory behavior” is an impulse beyond our control. This is a distinctly modern idea, though one that expressed itself somewhat differently in the 19th century. At that time, polar explorers called it “Arctic fever” a metaphor that was appropriate for an era afflicted by contagious disease. I find it interesting that late 20th century audiences have placed this impulsive, cannot-be-reasoned-with desire for danger within the human genome.

One might argue that the idea of the D4Dr is rooted in modern scientific research, that it represents something real rather than the 19th century’s metaphor of “fevers.” Still this doesn’t explain why talk of the explorer gene continues today even after the scientific evidence has left it behind.

For example, the dopamine-craving would-be adventurer can still join the D4Dr Club which bills itself as “the ultimate social club for adventure seekers of all types.”

No genetic testing is necessary. If you have an elongated D4DR, you probably know it. Be proud of it! Flaunt it! Whatever your ‘thing’ is – Adventure Travel, Extreme Sports or if you just like an adrenaline rush.

Membership benefits include a newsletter, inclusion in studies about the D4Dr gene, and a discount on flak jackets.

Mountains of the Moon

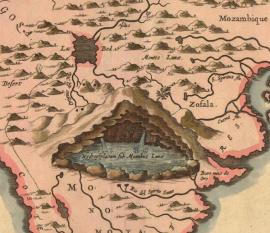

Mountains of the Moon, detail of 1655 Kircher Map of Africa

In 1788, twenty years after sailing into the Pacific with Captain Cook, Joseph Banks turned his attention to the next riddle of geographical science: the exploration of Africa. In St. Albans Tavern in London, Banks and the other members of the elite Saturday Club drafted a proposal of action:

Resolved: That as no species of information is more ardently desired, or more generally useful, than that which improves the science of Geography; and as the vast Continent of Africa, notwithstanding the efforts of the Antients, and the wishes of the Moderns, is still in a great measure unexplored, the Members of this Club do form themselves into an Association for Promoting the Discovery of the Inland Parts of that Quarter of the World.

The Saturday Club acted quickly. It endorsed the resolution, established an Association, put together an expeditionary fund, and commissioned John Ledyard (also a veteran of Cook’s voyages) to cross the African continent from east to west. Ledyard arrived in Egypt ready to complete the “efforts of the Ancients” but was struck down by illness in Cairo. He died before his boots got sandy.

Ledyard’s death was a disappointment to the Association, but it couldn’t have come as much of a surprise. Africa had proved itself resistant to European efforts for over three centuries. The first forays into Africa began badly. In 1446 Portuguese mariner Nuno Tristão took twelve men up the Gambia River in pursuit of Africans and riches. Tristão was attacked by Gambian tribesmen and killed along with half of his party.

The Portuguese learned from Tristão’s mistake. When they returned to West Africa, they abandoned their plans to explore and conquer the interior, preferring to set up outposts or “feitorias” on the coast from which they could trade with African kingdoms of the interior.

Other factors inhibited exploration as well. The inhospitable conditions of the Sahara made overland expeditions difficult. The great rivers of Central Africa seemed more promising, but they were filled with cataracts that made it impossible to travel far by boat. Malaria felled Europeans who traveled inland, and sleeping sickness (trypanosomiasis) not only attacked humans but horses. The horse, so effective as a weapon of war for Europeans battling the Incas in the New World, proved useless in European efforts to dominate Central Africa.

Cataract on the Congo River

Despite Africa’s importance in the Atlantic economy as a source of slaves and gold, then, it remained poorly understood in Europe. As a result, it remained a place of mythical and geographical speculation: on the source of the Nile, the riches of Timbucktoo, the Gold Mines of Ophir, the trans-continental mountains of Kong, and the mysterious Mountains of the Moon.

This explains the power of Africa in the Western imagination even late into the nineteenth century. For writers and artists, Africa became a canvas upon which almost anything could be painted. In Anglo-American literature, Africa found a home in the work of dozens of writers including H. Rider Haggard (King Solomon’s Mines, She), Joseph Conrad (The Heart of Darkness), and Edgar Rice Burroughs (Tarzan). Interestingly, the Africa of these works was background rather than foreground, a region made dark (morally, racially, and geographically) so as to better illuminate its protagonists — Allan Quartermain, Charles Marlow, Lord Greystoke — as they found adventure and enlightenment.

How such ideas were projected upon the surface of maps is the focus of Princeton’s excellent online exhibition, To the Mountains of the Moon: Mapping African Exploration, 1541-1880. Created by curator John Delaney, To the Mountains of the Moon offers a history of Africa as seen through European eyes.

As one might expect, early Renaissance maps of Africa were colorful, fantastical documents. What they lacked in credible information they compensated for with a rich palate of speculation. On Sebastian Münster’s 1554 map of Africa one finds the home of the mythic Christian hero, Prester John, as well as a tribe of one-eyed giants, the dough-faced Monoculi, who sit above the bight of Africa.

Sebastian Munster's 1554 Map of Africa (detail)

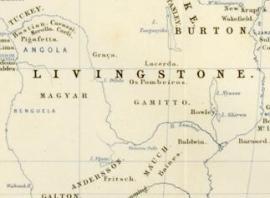

Nineteenth century maps added precision and sophistication. Gone are the mythic tribes and gold mines of early maps along with the chatty notes in Africa’s margins about river currents, astronomical observations, Biblical figures, and anything tangentially related to the continent.

Yet the later maps leave out Africans too. If Prester John and African cyclops are not representative of Africa’s peoples, at least they show it to be a place of human action and habitation. While some nineteenth century maps — by John Tallis and Victor Levasseur — present ethnographic scenes in the margins, others — such as William Winwood Reed’s Map of African Literature — shows the continent as a white text, tabula rasa, for the names of European explorers. “LIVINGSTONE” stretches across Central Africa from Mozambique to the mouth of the Congo River. Which of these maps – Munster’s or Reed’s – shows the greater distortion?

Winwood Read, Map of African Literature, 1910 (detail)

Despite the excellent maps and essays, the menus of the exhibition are not very clear. It’s easy to get lost and miss a map or two on the way out. This didn’t stop Stanley. It shouldn’t stop you.

Polar Hoaxes and Lost Worlds

A century ago this week Robert Peary and Frederick Cook locked horns in the “The North Pole Controversy,” an epic media battle that dominated news on both sides of the Atlantic for months. For readers it became a scandalous and impossibly compelling story, a post-Victorian Jon vs. Kate with furs and dogs.

John Tierney

John Tierney took up the story in the New York Times yesterday morning. To Tierney’s credit, he avoids the temptation to spend his entire column regaling the reader with evidence of Peary or Cook’s rightful attainment of the Pole. (He does take a position: neither man made it).

Instead he takes an interesting behavioral, rather than historical, approach to the question: why do the supporters of both explorers defend their man against all reasonable arguments? The answer, he argues, is that they become psychologically (perhaps neurochemically) committed to their candidate in a manner that is hard to alter. The use of the word “candidate” here is intentional since Tierney reports that this phenomenon is well measured in people supporting politicians and political parties.

Map of the "lost world" of Mount Bosavi

Also reported yesterday was the discovery of a “lost world” in Papau New Guinea. A team of scientists (big discoveries always follow sentences that begin with ”A team of scientists…”) discovered a unique, pristine ecosystem in the crater of Mount Bosavi. The team found more than forty new species, including the world’s smallest parrot, the world’s largest rat, and a herd of grazing brontosauruses. (I’m making up the rat part).

The use of ‘Lost World’ is an interesting way to describe this ecosystem not simply because it conjures images of Jurassic Park, Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1912 novel of the same name, and a whole genre of early twentieth-century adventure books, but because it’s not an obvious (and therefore not an unconscious) description of Mount Bosavi.

Accounts of the volcano, its geographical and biogeographical riches, have been appearing for forty years in academic journal (see for example Records of the South Australian Museum 15 (1965): 695-6; Mammals of New Guinea (1990): 236) and even further back in popular literature. Jack Hides and other Australians were writing about the Mount Bosavi in the 1930s.

Bosavi Woolly Rat, photo credit: Jonny Keeling

But “Lost World” sounds better than “Relatively Unknown Ecosystem” especially if it’s timed to coincide with a 3-part BBC Special on the expedition (titled “Lost Land of the Volcano”). Perhaps these are the necessary evils of science reporting in the digital age, a realm in which writers have two or three seconds to convey meaning and produce interest. Maybe these are the white lies required to raise the profile of meaningful and interesting projects. “Lost Land of the Volcano” pulled in 4.1 million viewers last night, an 18% share. Maybe the title of this post should be “Cow-Sized Rat Kills Cannibal, Saves Scientist.”

Where No ENFP Has Gone Before, Part II

(For Part I, go here)

I first took the Myers Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) when I was a junior in high school. This was a good time to take it since, like most sixteen-year-olds, I was self-absorbed enough to think I should spend more time trying to figure myself out.

The test labeled me as an ENTP: Extroversion, Intuition, Thinking, Perceiving.

I was a clear extrovert, someone who Jung describes as gaining energy from the world around them, or in my case, trying to set fire to the world around them. Introverts like Jung find energy through reflection. Thinking first, acting second. An interesting idea.

I also tested strongly intuitive, or as the MBTI would observe, I gathered information as concepts and abstract patterns rather than as concrete, immediate facts available to the senses.

One axiom of the MBTI is that personality types are stable, more or less. As this idea goes, the psyche sets up basic patterns of gathering, interpreting, and acting on information quite early, by age three or four.

Yet critics of the MBTI such as Paul Matthews point out that people who take the test often get different answers. My testing history confirms this as well. In high school, the MBTI tagged me as a thinker rather than feeler, deciding issues on logical and consistent premises.

When I took the test again last week, I had swung over to the feeling side of the spectrum, making decisions based upon personal association or empathy more than general principles. That a person’s psychological type seems squishy, mutable over time, is one of many criticisms leveled at the MBTI, one that challenges its claim to measure meaningful psychological differences.

Still, my MBTI evaluation has been stable other than that, particularly in the final category of perceiving/judging which evaluates how people process information. Strongly judging individuals tend to like settling matters and, as a result, gather information in order to make decisions and tie up loose ends.

Those with strong perceiving tendencies (of which I am one) gather information like rodents in November, amassing it without end. Perceivers are the hoarders of ideas, stowing and revising them even though it keeps things unsettled. They have messy desks.

Driving on Rt 6 in Wellfleet last week, my wife Michele (an INFJ) wondered how her students might type characters in her lit courses. Ahab would have to be an INTJ. The Great Gatsby? ESFP I think.

The conversation brought me back to a post I wrote last year about The Explorer Type. At the time, I was thinking about how certain explorers, such as Roy Chapman Andrews and Louis Leakey, took on similar cultural personae: popular outsiders who contributed to, but were not a part of, the academic establishment.

Was there something deeper here? A psychological type that lay behind the public persona? The ENTP personality type (Extrovert, Intuitive, Thinking, Perceiving) is often labeled “The Inventor-Explorer.” Other analyses of Myers-Briggs tag INTP (Introvert, Intuitive, Thinking, Perceving) as the rightful home of this type. Yet what spotty data exists on this subject shows that real explorers, such Chuck Yeager and Alan Shepard, test as ISTPs (Introvert, Sensing, Thinking, Perceiving).

Alan Shepard

Then again, test pilots and astronauts offer a narrow field of explorers. Reading Goethe and ranging over the mountains of South America, would Alexander von Humboldt have been an ISTP? Never. An ENTP if ever there was one.

Nor should the military discipline and technical demands of modern spaceflight necessarily point to controlled, process-oriented types such as ISTPs. The world’s most famous astronaut is a confirmed ENFP.

An ENFP seeks out new worlds.

Take a quick MBTI assessment here.

Type profiles are available here.

Other posts on exploration and personality: