Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationPrester John

For Europeans in the 1450s, the Western Ocean (or the Atlantic as we now call it) was a frightening place. Unlike the cozy, well-mapped Mediterranean which was surrounded by three continents, the Western Ocean was unbounded, poorly understood, and filled with dangers.

The dangers were not the threat of sea monsters or falling off the edge of the world. Medieval sailors and geographers understood that the earth was spherical. (The idea that they thought it was flat is a fantasy conjured up by Washington Irving in his 1828 biography of Christopher Columbus.)

Rather, the real threat was the ocean itself. Expeditions that followed the West African coast had revealed strong winds and currents that made travel south (with the current) easy, but return extremely difficult, especially with vessels that could not tack close to the wind. By the 1430s, Europeans had even identified a spot on the West African coast, Cape Bojador, as the point of no return.

And yet Europeans, led by the Portuguese, continued to push further south despite this risk. They developed trade factories off the west coast of Africa which exchanged Europeans goods — horses, wool, iron — for gold, ivory, and slaves. And ultimately they followed the African coast around the Cape of Good Hope and into the Indian Ocean, reaching the Indies — the holy grail of luxury items — in 1498.

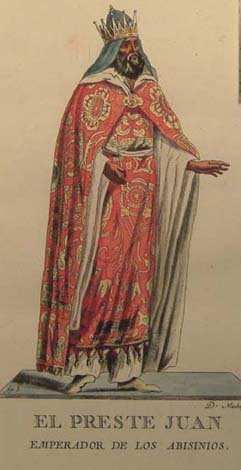

All of this makes European exploration seem logical and methodical, driven by the promise of riches. Yet Europeans were interested in more than slaves and spices. Africa attracted Europe’s attention because it was considered the most likely location of Prester John, legendary Christian king and potential ally in the fight against the Muslims who occupied the Holy Land.

Historians have long placed Prester John within the category of myth, and in so far as myths describe “traditional stories, usually concerning heroes or events, with or without a determinable basis of fact” I suppose Prester John qualifies.

But “myth” has subtler, darker meanings. The world is filled with traditional stories that have a tenuous relationship to observable facts: the Gospels, the Koran, and the Torah are filled with them. Yet we describe these stories as “beliefs” out of faith or respect. We usually reserve the word “myth,” however, for those stories — unicorns, leprechauns, a living Elvis — that we dismiss as untrue.

The point here is not to say that Prester John was real, but to say that in characterizing him as a mythic figure, historians have tended to discount his serious influence on European exploration and discovery.

This is a central argument of historian Michael Brooks in his excellent thesis, Prester John: A Reexamination and Compendium of the Mythical Figure Who Helped Spark European Expansion. Brooks shows that, while it might be clear in hindsight that Prester John was more fable than reality, it was not clear to Europeans in the 15th and 16th centuries, all of whom could point to multiple accounts of the Christian king from different, trustworthy sources. The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, one of the most popular books in late medieval Europe, even offers a first-hand account of Prester John’s palace:

He dwelleth commonly in the city of Susa. And there is his principal palace, that is so rich and so noble, that no man will trow it by estimation, but he had seen it. And above the chief tower of the palace be two round pommels of gold, and in everych of them be two carbuncles great and large, that shine full bright upon the night. And the principal gates of his palace be of precious stone that men clepe sardonyx, and the border and the bars be of ivory. [Mandeville quoted in Brooks, 87]

On the basis of these multiple, mutually supportive documents, Dom Henrique (Henry the Navigator) charged his explorers to bring back intelligence about the Indies and of the land of Prester John. This was not merely an addendum to their orders for geographical discovery. Argues Brooks:

Without the lure of making political connections with the supposed co-religionist Prester John in the struggle against the Islamic world, the European history of overseas expansions would likely have taken a different course [3].

This serious, sustained interest in Prester John helps explain the longevity of the legend well into the seventeenth century. I could not help seeing many similarities in Brooks’ account of Prester John with other stories of exploration. The one I have written the most about, the theory of the open polar sea, has also been discounted by historians as “myth” even though it was taken very seriously by scientists, explorers, and geographers in the nineteenth century, shaping the missions of numerous explorers.

Brooks’ thesis is available in pdf here.

He also posts a number of articles and reviews on history and exploration on his blog, historymike.

Thanks Research Blogging!

Time to Eat the Dogs has been named a 2010 finalist for best blog in Social Science and Anthropology by Research Blogging. The awards panel received four hundred nominations and then selected 5 to 10 of the best blogs in each field.

For those who don’t know about Research Blogging, it is a site for “identifying the best, most thoughtful blog posts about peer-reviewed research.” They have over 1000 registered blogs and an archive of 950 research based blog posts.

Registered bloggers at Research Blogging.org will begin voting for winners in each category on 4 March, so if you are a serious blogger and fan of Time to Eat the Dogs, please register and vote.

NASA and the Ghosts of Explorers Past

By Michael Robinson and Dan Lester

NASA has always stood at the fulcrum of the past and future. It is the inheritor of America’s expeditionary legacy, and it is the leading architect of its expeditionary path forward. Yet the agency has found it hard to keep its balance at this fulcrum. Too often, it has linked future projects to a simplistic notion of past events. It has reveled in, rather than learned from, earlier expeditionary milestones. As NASA considers its future without the Constellation program, it is time to reassess the lessons it has drawn from history.

For example, when U.S. President George W. Bush unveiled the Vision for Space Exploration (VSE) in 2004, the administration and NASA were quick to link it to the 200th anniversary of the Lewis and Clark expedition, stating in the vision: “Just as Meriwether Lewis and William Clark could not have predicted the settlement of the American West within a hundred years of the start of their famous 19th century expedition, the total benefits of a single exploratory undertaking or discovery cannot be predicted in advance.” In Lewis and Clark, NASA saw a precedent for the Vision for Space Exploration: a bold mission that would offer incalculable benefits to the nation.

Yet this was a misreading of the expedition. The Lewis and Clark expedition did not leave a lasting imprint on Western exploration. The expedition succeeded in its goals, to be sure, but it failed to communicate its work to the nation. The explorers’ botanical collections were destroyed en route to the East Coast, their journals remained long unpublished, and the expedition was ignored by the press and public for almost a century. In 1809, 200 years ago last September, a despondent Lewis took his own life. NASA might do well to reflect on this somber anniversary in addition to the more positive one used to announce the Vision for Space Exploration in 2004. Doing exploration, Lewis reminds us, often proves easier than communicating its value or realizing its riches.

NASA should also remember the anniversary of Robert Peary’s expedition to reach the North Pole, completed a century ago last September. Peary’s expedition, like the ones envisioned by the Vision for Space Exploration, was a vast and complicated enterprise involving cutting-edge technology (the reinforced steamer Roosevelt) and hundreds of personnel. Peary saw it as “the cap & climax of three hundred 300 years of effort, loss of life, and expenditure of millions, by some of the best men of the civilized nations of the world; & it has been accomplished with a clean cut dash and spirit . . . characteristically American.”

Yet Peary’s race to the polar axis had little to offer besides “dash and spirit.” Focused on the attainment of the North Pole, his expedition spent little time on science. When the American Geographical Society (AGS) published its definitive work on polar research in 1928, Peary’s work received only the briefest mention. Indeed, the Augustine committee’s statement that human exploration “begin should begin with a choice of about its goals – rather than a choice of possible destinations” would have applied itself equally well to the race to the North Pole as it does the new did recent plans to race to the Moon.

But the most important anniversary for NASA to be considering is the recent 400th anniversary of Galileo’s publication of “Sidereus Nuncius” (“Starry Messenger”), a treatise in which he lays out his arguments for a Sun-centered solar system. Was Galileo an explorer in the traditional sense? Hardly. He based his findings upon observations rather than expeditions, specifically his study of the Moon, the stars, and the moons of Jupiter. Yet his telescopic work was a form of exploration, one that contributed more to geographical discovery than Henry Hudson’s ill-fated voyage to find the Northwest Passage made during the same year. Galileo did not plant any flags in the soil of unknown lands, but he did something more important: helping to topple Aristotle’s Earth-centered model of the universe.

As NASA lays the Constellation program to rest, the distinction between “expedition” and “exploration” remains relevant today.While new plans for human space flight will lead to any number of expeditions, it doesn’t follow that these will constitute the most promising forms of exploration. Given our technological expertise for virtual presence – an expertise that is advancing rapidly – exploration does not need to be the prime justification for human space flight anymore.

The Augustine committee has shown the courage to challenge the traditional view of astronauts as explorers in its “Flexible Path” proposal, a plan to send humans at first into deep space, perhaps doing surveillance work on deep gravity wells, while rovers conduct work on the ground. Critics have derisively called it the “Look But Don’t Touch” option, one that will extend scientific exploration even if it does not include any “Neil Armstrong moments.”

Yet perhaps 2010 is the year when we challenge the meaning of “exploration.” For too long, NASA has been cavalier about this word. Agency budget documents and strategic plans continue to use it indiscriminately as a catch-all term for any project that involves human space flight. Yet this was not always the case. The National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958, the formal constitution of the agency, doesn’t mention the word in any of the eight objectives that define NASA’s policy and purpose. Rather, NASA’s first directive is “the expansion of human knowledge of the Earth and of phenomena in the atmosphere and space.”

Geysers in the southern hemisphere of Enceladus, photographed by Cassini spacecraft, 27 November 2005

Perhaps the best way forward, then, starts with a more careful look back. The world has changed since Lewis and Clark, with technology that would have stunned the young explorers. In the year of “Avatar,” we need to think differently about the teams who direct rovers across the martian landscape, pilot spacecraft past the geysers of Enceladus and slew telescopes across the sky. These technologies are not static in their capabilities, nor as are the humans who control them. Their capabilities advance dramatically every year, and the public increasingly accepts them as extensions of our intellect, reach, and power. As Robert Peary’s quest for the North Pole illustrates, toes in the dirt (or in his case, ice) don’t necessarily yield new discoveries.

Of course robots and telescopes can’t do everything. A decision that representatives of the human species must, for reasons of species survival, leave this Earth and move to other places would make an irrefutable case for human space flight. But that need has never been an established mandate. It isn’t part of our national space policy. As we celebrate NASA’s 50th anniversary, NASA begins its sixth decade, do we have the courage to look beyond our simplistic notions of exploration’s past to find lasting value in the voyages of the future?

Michael Robinson is an assistant history professor at the University of Hartford’s Hillyer College in Connecticut. Dan Lester is an astronomer at the University of Texas, Austin.

This essay appears here courtesy of Space News where it was published on 8 February 2010.

Spring Cleaning

I’ve been in semi-hibernation for the last few months and haven’t been posting as often. But its time for spring cleaning at Time to Eat the Dogs. Have courage, reader: February is really the cusp of spring. Beneath that hard macadam of ice, crocuses are leaping out of the ground.

First, I’ve added some new links, which, because of the Illiad-sized list I’ve made in the fourth column, probably are not obvious. They are all good sites and worth a visit:

Those Who Dared (listed under Exploration Journals, Organizations, and Blogs) is a new exploration blog written by Richard Nelsson, chief librarian of the Guardian and the Observer. Nelsson’s a fine writer, the author of two books on exploration, and he posts frequently.

Savage Minds is a new group anthropology blog which has good posts and a killer list of anthropological links. The title comes from Claude Levi-Strauss’s book of the same name, and the play on words (really only funny in French) is his too.

WINGS Worldquest (listed under Exploration Journals, Organizations, and Blog and Women Explorers) is an agency which promotes women explorers throughout the world. It organizes lectures, book talks, awards dinners etc. on a wide range of subjects in science, travel, and exploration.

The Renaissance Mathematicus blog (listed in History, Science, and Anthropology) written by Thony C., tackles a number of issues in the history and philosophy of science. Thony hosted the Giants Shoulders #19 in mid-January which gives a good summary of current history of science writing in the blogosphere.

INUIT: Contact and Colonization (listed under Polar Exploration) is a new educational site for Inuit contact with traders, explorers, and whalers, focusing on native practices and experiences.

Heritage in Maine written by anthropologist Patricia Erikson features a number of posts on Maine native Josephine Peary (listed under Polar Exploration), a fascinating, complicated explorer who worked at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Second, you can follow the blog now via email subscription, RSS feed, or twitter feed, all available in the third column.

I’ve never seen the value of twitter to my work since issues in the history of exploration rarely unfold quickly. But it’s effective as a communication tool since I receive a steady stream of announcements about exploration events, articles, conferences, and research that never make it to my posts or links. I now announce my blog posts on Twitter as well

If you would like to follow this extra stream of information, I have provided a twitter feed that you can follow (or subscribe to) in column three. Once I have the USB port implanted in my neocortex, new posts will become available every waking moment. Surgery is scheduled.

Happy Spring!

The Death of the Constellation Program

Obama’s 2010 budget proposal is a radical document. Not because it runs the biggest federal deficit in American history ($1.53 trillion). Posting record deficits has become commonplace since Reagan started doing it in the 1980s. No, it is radical because it tries something new: killing off a multi-billion dollar NASA program that has strong support in Congress.

Constellation grew out of President George W. Bush’s Vision for Space Exploration, which he announced shortly after the Columbia Shuttle disaster of 2003. Bush’s plan was visionary: a plan to design and build boosters and spacecraft capable of returning astronauts to the Moon and, ultimately, Mars.

But visionary does not equal smart. The Constellation Program failed because it fell into the same trap that Apollo did in the 1970s: it was a massively expensive public program that, while symbolically impressive, lacked practical, real-world benefits that could match its $97 billion price tag (GAO-estimated cost through 2020).

Indeed, the Constellation Program was so colossal that it stood poised to suck the life out of every other NASA initiative, particularly space science projects that did not require humans, crew modules, or moon buggies to conduct research.

The technology of the Constellation Program may have been new but the arguments were old, a list of reasons for pursuing human space flight that have been used to justify missions for the past forty years:

1. Human space flight is an extension of humanity’s quest to explore and therefore cannot, and should not, be stopped. To do so would be to blunt human curiosity and deny human nature. In truth, exploration has been pursued for many reasons, of which curiosity has usually ranked low on the list. Even if we accepted, for the sake of argument, that an exploration impulse that is part of human nature, it still does not mean that we should obey this impulse. This is a classic “naturalistic fallacy” which says something is good because it is natural. Social Darwinists used this line of reasoning to justify poor treatment of workers and colonial subjects on the idea that survival of the fittest was natural and therefore should be allowed to run its course.

2. Human space flight will offer unforeseen benefits to science and technology. This may be true. Or maybe not. It’s hard to say really because proponents admit that any benefits are unforeseen. Still it seems an odd toss-of-the-dice way to spend public money. Would we trust a general who defended his plan of attack on the unforeseen possibilities of victory? Would shareholders trust a company selling products with unforeseen potentials of profit?

3. If we abandon human space flight, we will soon be outpaced by the China, Russia, India, [insert developing industrial nation] in the space race. The United States did gain prestige from landing astronauts on the moon in 1969, showing up our Cold War rival, the Soviet Union. But how much did that prestige, or “soft power” actually benefit the United States? Prestige did not stop the Vietnam War, or the Arab Oil Embargo, or the onset of stagflation. How much, then, is this type of prestige worth in the post-Cold War Age, a time when the United States is, arguably, supposed to reap the benefits of belonging to a multilateral world? What does the United States gain in winning the space race against China when they are losing the economic race to China back on Earth?

4. Human space flight is the first step in the human settlement of space, a process vital to continuation of the species. The idea that astronauts are really 21st century pioneers is a romantic one, but unrealistic. Going to the moon (or Mars) is a lot easier than settling there. Perhaps the real question here is why proponents of space settlement are so willing to give up on planet Earth? Global warming? Nuclear war? Overpopulation? This begs the question: if we cannot take care of a 197 million square mile habitat that’s free, self-regulating, and self-sustaining, what makes us think that we’re going to do any better on multi-billion dollar artificial habitats on other planets?

It’s time for NASA to think differently about space exploration. The Obama budget requests $18 billion for the agency over the next five years, an increase from the current budget. Now NASA has the time and the money to think about new ways of moving forward. Bravo to the Obama Administration for forcing the issue.