Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationExploration Roundup

Notes from Montreal

Montreal: place of cobblestones and canals, of spicy Pho and this year’s History of Science Society (HSS) meeting (and Philosophy of Science Association meeting, PSA).

The conference was my introduction to the Toronto bloggers who are tearing through the HSS/PSA neighborhood. I met Jaipreet Virdi who writes From the Hands of Quacks and Aaron Wright, author of False Vacuum. Justin Curtis and Mike Thicke from The Bubble Chamber were also in attendance but we didn’t cross paths. To all of you: keep up the excellent work!

Of the travel and exploration panels I attended, I was most impressed with a talk by Christopher Parsons (University of Toronto) on 17th century French settlers in North America. He argued that these settlers organized species according to a generalized “folk taxonomy.” While exploration scholars often highlight reports of marvels and wonders, Parsons described the reverse: settlers cataloging new plants and animals according to the most general and conventional of categories.

A Short Rant

One thing I also appreciated about Christopher’s talk was the way he delivered it: framed by issues, guided by images, and given from notes. Some other presenters did not do these things adequately: giving little context, offering no images or outlines, and reading from the text.

I don’t understand this.

Most historians make their living by teaching. Most of the ones I know are attentive, innovative, passionate teachers. They care about communicating ideas. They engage their students and foster their interests in history.

What happens when we go to conferences? What force transmutes vibrant instructors into paper-reading scholastics? Who decided that the best way to present one’s ideas was to sound like a medieval instructor lecturing at the University of Paris?

I’ve heard many arguments for why academics read papers: “It’s the only way to fit my material into 20 minutes.” “I need to be precise.” “I get too nervous to go from notes.””I can write my papers in a conversational style.”

All of this may be true but it doesn’t change the fact that someone speaking from notes is easier to understand than someone reading from a text; the words and cadence are more natural and, I think, better able to carry the weight of a complex argument. I don’t have hard data on this, but consider this: most of us would recoil at the idea of reading a lecture to our students. If we wouldn’t suffer this upon students, why do it to our peers? What’s the point of maximizing time, precision, or peace of mind if, in the process, we lose the attention of our audience?

Ethics of Exploration

In other news, Peter Stanford challenges the heroism of modern day adventurers in his article in the Independent (Thanks to Richard Nelsson for alerting me to this). The article complements longer treatments of this issue by Jon Krakauer (Into the Wild) and Maria Coffey (Where the Mountains Casts Its Shadow).

Spaceflight

Curtis Forbes, writing at The Bubble Chamber, discusses the discovery of the exoplanet Gliese 581g and the hype its generated in the media as the “Goldilocks Planet.” Forbes convincingly argues that the eagerness to imagine this world as an earth-like place tells us more about culture here than environmental conditions there. Meanwhile, Cosmic Variance has raised questions about the concentration of space science funding into the James Webb Space Telescope which is scheduled to replace the Hubble Telescope in 2014.

As NASA enters the post-Constellation era, I think we will be seeing a lot more debates about science and space funding.

Academics vs. Explorers

Last week explorer Mikael Strandberg published an interesting post on his blog about Academics vs. Explorers . The post described some of the tensions that exist between explorers and university professors on issues related to exploration. I think that many of Mikael’s points ring true: academics are less than comfortable at times collaborating with travelers and explorers on matters of geography, science, anthropology, and exploration.

Why? I think there are a couple of reasons.

First, academics usually approach their subject matter from a specific viewpoint or research methodology. For example, anthropologists, field biologists, archeologists, and historians all have different frameworks for understanding the world and its peoples. Information obtained from explorers (or other fields) often doesn’t fit very well within these frameworks and, therefore, remains difficult to integrate. Most travelers and explorers, by necessity, need to approach new peoples and new regions with versatility, sensitivity, and creativity. They do not have the time to settle in one place the way an anthropologist does. They cannot carry thousands of pounds of equipment the way archeologists do. They cannot afford to set up their travels as controlled experiments.

Second, academics often don’t know how to categorize explorers. For example, as a historian of exploration, I am interested in the culture, experience, activities, ideas, and biases of explorers. This is the subject of my research. Working with explorers is exciting for me because it sometimes gives me insight into the historical expeditions that I focus on in my work. But it can sometimes also be uncomfortable because I don’t know which hat to wear. Am I a colleague listening to a fellow expert in the field? Or am I an anthropologist, analyzing my subject for information about his or her ideas, beliefs, and behaviors?

Still I think that academics and explorers would benefit from closer contact.

One way explorers might help professionals in general (and academics in particular) is in thinking outside the disciplinary box. Sometimes my greatest insights come from sources far removed from my field of expertise in the history of science and exploration. As Will Thomas has pointed out at Ether Wave Propaganda, historians sometimes forget that their “subjects” are often sophisticated observers of events and their place within them.

One way that explorers might benefit from academics is in looking at exploration more critically. I often hear travelers and explorers speak about exploration in rather visionary terms: as a way of escaping overly commercialized and routinized life in order to find a “core” self….or as a deep-seated, instinctive behavior that humans express in order to achieve their full humanity. While these ideas are inspiring, they don’t really conform with data on the history of explorers and exploration.

Christopher Columbus, Robert Peary, and NASA astronauts all reached “new worlds” far away from the civilizations they knew. Yet all of them remained deeply invested in the practical and personal payoffs of exploration back home (eg. fame, glory, professional advancement). My research leads me to believe that the desire to explore flows as much from the influence of modern culture as it does from our innate drives or inner curiosity.

In the end, however, I am fine if academics and explorers don’t see eye-to-eye as long as they keep talking to each other face to face.

For other posts here on related subjects see:

The Myth of Pure Experience

The Problem of Human Missions to Mars

The Explorer Gene

Exploration Round-Up

So much exploration news rolls through the wires that it’s impossible to write posts about all of it, even a small fraction of it. So I tweet when I can, but 140 characters is not a lot of space to offer analysis or even useful links. So I am going to the occasional round-up here: a short, annotated, links page to developing stories. Think of it as a expeditionary snack: more calories than a tweet, less filling than a post.

Polar Regions

The biggest exploration story out of the high Arctic in recent weeks is adventurer Bear Grylls’s report of finding human bones, tools, and large campfire remains near King William’s Island. He suggested that these might have been the remains and artifacts of Sir John Franklin’s doomed expedition of 1845. Russell Potter has been following the story closely on his blog Visions of the North.

Space

Roger Launius’s Blog profiles former NASA administrator Dan Goldin lecture about NASA’s efforts in astrobiology. The Journal of Cosmology just published a special issue Colonizing Mars: The Human Mission to the Red Planet. Many of the essays are quite pro-Mars. Mine is not. In The Problem of Human Missions to Mars I discuss the reasons why plans for human missions to Mars (and there have been many) never seem to go anywhere.

Mountains

Mikael Strandberg takes up the issue of Fakes and Cheats in exploration, focusing on the motives of explorers in lying about their claims. This issue has a long history, one that I’ve written about here in regards to the North Pole Controversy of 1909. Yet its a subject that never seems to goes away. The claims of high-altitude climbers routinely come into question today. In January, ExplorersWeb wrote an editorial about rampant fabrication of claims by climbers in the Karakorum. More recently, Jake Norton, author of The MountainWorld Blog, discussed the revelation of speed-climber Christian Stangl’s faked climb of K2. The BBC also challenged Oh Eun-Sun’s claim to be the fastest women to climb all fourteen 8,000 meter peaks. Yet not everyone’s ducking the hard routes. Those Who Dared profiles the survival stories of climbers who barely made it back. And for some brilliant photos of climbers in the field, The MountainWorld Blog features photos from Sir Younghusband’s 1903 expedition to Tibet. The Asia Society’s Rivers of Ice project offers a more sobering photographic record of the Himalaya today, chronicling, in mega-pixel detail, the effects of global warming on glaciers.

Mr X

There is a scholar, call him Mr X, who received his training within the academy, but who found it wasn’t enough. He wanted more: to move outside of his wonky circle of colleagues, to engage the public, to communicate ideas in a manner that was artful as well as illuminating.

While his peers wrote difficult books and debated obscure issues at their meetings, Mr X took part in the communication revolution that was bringing academic ideas into greater contact with the wider world. He wrote shorter pieces for broader audiences, telling one colleague “Publish small works often and you will dominate all of literature.” So when Mr X was offered a position far away from his bustling city home, he took it, feeling that his community was no longer defined by geography but by ideas, communicated through the new social technologies.

The new social technologies wern’t blogs or Web 2.0 applications, but the pamphlet and the salon. Mr X is not Steven Jay Gould or PZ Myers but Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis, an 18th century French explorer and polymath who led a geodetic expedition to Lapland in 1736.

Maupertuis is usually remembered as the scholar who described the actual shape of the earth by measuring a degree of arc at high latitude. In so doing, he helped settle a dispute with French cartographer Jacques Cassini over whether the earth was prolate (that is, longer along its N-S axis), or oblate (longer along its diameter at the equator). Cassini believed that the earth was prolate like a lemon. Maupertuis, following in the footsteps of Newton, helped prove that it was oblate like a jelly donut.

Yet as Mary Terrall points out in her book The Man Who Flattened The Earth: Maupertuis and the Sciences of the Enlightenment, Maupertuis’s most interesting work takes place back home as he tries to make a name for himself in this new theater of conversation, a world that connects elite academies and educated polite society.

As I read about the radical effects of social technology on academic writing and reputation today, I wonder: how much of this is really new? Perhaps the boundaries between elite institutions and general public have always been squishier than we’ve made them out to be. Blogs and twitter feeds feel so new, so world changing, because they have in fact changed the world we live in, the way we communicate with friends, peers, and random passers-by. Yet it’s bound to feel like this. The flood feels strongest when you’re standing in the middle of the stream. The story of Maupertuis makes me think that it is a seasonal event, a spring flood that returns with some regularity, the latest iteration of social technology (and sociable science writing) that probably dates to the printing press. Vive le café.

New With Age

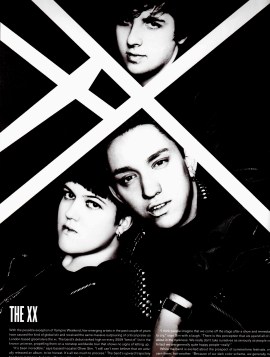

I downloaded the album XX this morning from Itunes. I’d heard bits and pieces of it over the past few months as it trickled through the estuaries of popular culture into my living room: AT&T commercials, HBO shows, and finally an interview with the lead singers Romy Croft and Oliver Sim on National Public Radio.

The shy, breathy duets of Croft and Sim sounded to me like Everything But the Girl. Lead guitarist Baria Querishi’s spare treble notes brought memories of New Order, the Cure, and Roxy Music. The XX looked new, but they sounded old, twenty-somethings channeling the spirits of the Second British Invasion. I felt conflicted at the end of it all: the music compelled attention, but at the same time, seemed derivative.

“Derivative” cuts deep, worse perhaps than “awful.” After all, there are gentler explanations for awful. It could mean that an artist is pushing through too many conventions, going farther than an audience is willing to follow. In this sense, today’s awful holds the promise of being tomorrow’s brilliant. Derivative, however, lives without hope. It can only been seen as an attempt at novelty that has fallen short, a poorly disguised act of mimicry.

Or are there other explanations for derivative? Though I heard other bands playing through XX, the label derivative didn’t really match my experience of listening to it. I like the album. I found myself listening to it again. It was in my head as I left the house. I turned it on when I got back home. Would I really be so patient with an album that was a complete knock off?

At some unconscious level, then, the XX provided something new.

Seen with the dispassion of distance, of course, there is no such thing as new. Music, like any other human expression, is forged in the crucible of culture. It cannot escape the conditions of its creation – whether you want to call it borrowing, inspiring, or mimicking. Originality in this sense is a myth. Everything grows from a source. “Nothing comes from nothing” says Parmenides (and Fraulein Maria).

Yet maybe the label derivative is born out of our emotional experience, rather than rational analysis, of art. In this sense, the sounds of older influences within new music are not just a product of the artist’s cultural borrowing, but of our own psychological interpreting. Perhaps, in other words, we are not cognitively prepared to experience things as new. How did I first experience other artists? My first encounters almost always followed the same pattern. I heard the old influences first: other bands that inhabited new music. And I can generalize further. All of my new experiences – music, trips abroad, new foods – come with reminders, comparisons, analogies with the old – the already known.

This is a well-demarcated phenomenon, particularly in studies of exploration. Christopher Columbus had never been to Asia, yet found in America all of the things that he expected to see there: cinnamon, Amazons, anthropophagi, and the Great Khan. As Anthony Grafton pointed out in New Worlds, Ancient Texts: The Power of Tradition and the Shock of Discovery, the New World didn’t look so new to Europeans at first. Columbus went to his grave thinking he had reached Asia. Only over time, as the New World became old so to speak, did it come to be framed as new, as other, as disorienting. The XX began with an old soul. Now it seems fresh. Newness, like cheese, gets stronger with age.