Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationBook Excerpt: A Labyrinth of Kingdoms: 10,000 Miles Through Islamic Africa

This month, W.W. Norton comes out with Steve Kemper’s new book, A Labyrinth of Kingdoms: 10,000 Miles Through Islamic Africa. It chronicles the scientific expedition of Heinrich Barth in 1849-1855. Barth explored Africa at a time when the continent’s relationship with the West was in transition. This was still the era of missionary explorers such as David Livingstone (exploring far to the south) yet in just two decades, a new generation of explorers such as Henry Morton Stanley would survey the continent as the opening act of the “Scramble for Africa,” a European land grab which would put Africa under colonial control for almost a century.

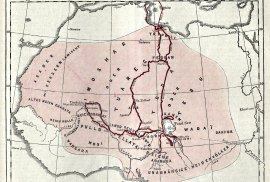

Below is an excerpt of the book in which Barth and his fellow scientist Adolf Overweg are traveling with a tribe of Arab raiders, the Welad Sliman, into Kanem, northeast of Lake Chad. Kemper also blogs about his experiences following in Barth’s footsteps here.

From Chapter 16: “The Horde of the Welad Sliman.” Reprinted from A Labyrinth of Kingdoms: 10,000 Miles through Islamic Africa by Steve Kemper. Copyright © 2012 by Steve Kemper. With the permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

“The next day the group rested at a camp on the edge of a river. “We had a good specimen to-day,” wrote Barth, “of the set of robbers and freebooters we had associated with in order to carry out the objects of the mission.” When a small caravan of Tebu people crossed the river near Barth’s group, the Welad Sliman seized their entire cargo of dates.

Barth’s troupe crossed the river the following day. The ferry consisted of six calabashes yoked together, on which the passenger sat, pushed by two swimmers. From this shaky perch Barth managed to take several measurements of the river’s depth and contours. On the other side, the Welad Sliman filched three sheep for supper. They also kindly cleared a spot for Barth’s tent. Then during the night they stole one of his valuable waterskins.

(“A new skin recently greased with goat or sheep fat is abominable,” wrote explorer Francis Rennel Rodd, “as the water becomes strongly impregnated with the reek of goat. But water from a good old skin can be almost tasteless, though such skins are hard to come by. Some of the water one has drunk from goatskins beggars description; it is nearly always grey or black, and smelly beyond belief.”)

The rulers of Bornu did nothing to protect the region’s beleaguered villagers from freebooters, yet squeezed the people for tribute. The villagers also paid off marauding Tuaregs. The Welad Sliman simply took what they wanted. Four days after stealing the dates, they plundered some cattle-herders, taking not only their milk but the containers. The herders appealed to Barth and Overweg, who recovered the vessels, empty, and apologized with some small presents. During the next day’s travel, while Barth bought milk from some cattle-herders, the Arabs stole one of the herders’ horses. Later that day the robbers snatched another cargo of dates, plus the ox carrying them. “And yet the people who were thus treated were subjects of the King of Bornu,” wrote Barth bitterly, “and the Welad Sliman were his professed friends and hirelings.”

Despite the violence and lawlessness, Barth tried to focus on his scientific mission and his faith in knowledge. “There was a feeble spark of hope in me,” he wrote, “that it would not always be so, and I flattered myself that my labors in these new regions might contribute to sow here the first germs of a new life, a new activity.”

There were compensations for his observant eye, starting with the peculiar landscape. To the north, sand hills rolled into the Sahara. To the south, marshy flats and lagoons led to the blue waters of the lake. On the grassy plain in between lived farmers and herders. The Arabs shot a beautifully patterned snake that Barth measured at eighteen feet, seven inches, with a five-inch diameter. The natives cut it open for the fat. After noting lots of elephant tracks and dung near the shoreline, Barth finally saw “one of the most interesting scenes which these regions can possibly afford”—a herd of ninety-six elephants, “arranged in a natural array like an army of rational beings, slowly proceeding to the water.” He sketched them.

Two days later, trying to find their way out of a “labyrinth of lagoons,” Barth’s horse panicked while trying to cross a deep bog and fell on its side, with Barth underneath. As both creatures thrashed to extricate themselves, the horse kicked Barth several times in the head and shoulders, without severe damage. “I had on this occasion a good specimen of the assistance we were likely to receive from our companions in cases of difficulty,” wrote Barth, “for they were looking silently on without offering me any aid.” Like vultures watching an animal stuck in a mudhole.

On October 1 they reached the outskirts of the Welad Sliman’s main camp. About 250 horsemen formed a welcoming line and greeted them with musket fire and wild war cries. At the Arabs’ urging, Barth and Overweg responded with the traditional gesture, galloping straight up to the line of horsemen and saluting them with pistol shots. (“This is a perilous sort of salutation,” wrote the explorer Dixon Denham, who knew first-hand. As he and his Arab companions galloped to greet the sultan of Mandara, they trampled and killed a mounted onlooker and broke his horse’s leg.)

Barth and Overweg were shown a spot to pitch their tents. “We had now joined our fate,” wrote Barth, “with that of this band of robbers.”

For Barth, the trip’s main purpose was to solve another geographical puzzle. The Bahr el Ghazal was a sandy valley lined with vegetation that sometimes contained water. Barth’s question: was it a source for Lake Chad, or an outlet? He asked the Welad Sliman’s young leader to arrange an excursion there, about 200 miles east. No, said the man, impossibly dangerous. Then maybe they could explore the eastern side of Lake Chad? Perhaps, said the man, since they were about to go raiding in that direction. In several ways this was not what Barth had signed up for, though he shouldn’t have been surprised.

The raiders didn’t move for several days. Barth, still weak from fever, welcomed the time to recuperate. He began learning Tebu. He also developed a taste for camel’s milk, which he began to prefer. “Milk, during the whole of my journey, formed my greatest luxury,” he wrote. But the milk in Kukawa disgusted him because the Kanuris added cow’s urine to it, to keep it from going sour.

One night there was some excitement when a prize female slave, captured as booty and destined for the vizier’s harem, ran off. The next morning they found her necklace, bloody clothes, and gnawed bones.

The Arabs broke camp on October 11 and rounded the northern edge of Lake Chad, heading southeast. Their camels carried empty sacks to hold plunder. They traveled in an atmosphere of threat and aggression, constantly on alert for attacks, their own or an enemy’s, since everyone in the region hated them. Scouts raced off to check every rumor about possible victims or assailants. Despite the oppressive heat, the horde camped in shade-less places to foil ambush by foes and wild beasts. It was physically and psychologically exhausting.

Barth and Overweg didn’t know the Welad Sliman’s objective or destination. On the route towards pillage, Barth dutifully recorded vegetation, geography, animal sightings, names of villages, and currency (white Bornu shirts). His information often came from the native peoples they passed, since they knew the region “so much better than that band of lawless robbers who took no real interest in it except as regarded the booty which it afforded them.”

On October 17, after an early start, they reached the edge of their goal—the territory of the Woghda, a Tebu tribe. The Welad Sliman prepared themselves for violence in time-honored ways, with fiery speeches and fierce cries. Galloping warriors waved white banners. To hide their approach, they camped without fires. “But as soon as it became dark,” wrote Barth, “very large fires were seen to the southeast, forming one magnificent line of flame”—beacons summoning the resistance. The Woghda would be ready for them.”

Steve Kemper has been a freelance journalist for more than 30 years. His first book, Code Name Ginger: the Story Behind Segway and Dean Kamen’s Quest to Invent a New World (Harvard Business School Press, 2003), was selected by Barnes & Noble for its Discover Great New Writers award. He has written for Smithsonian, National Geographic, National Geographic Adventure, National Geographic Traveler, Outside, Wall Street Journal, Yankee, National Wildlife, The Ecologist, Plenty, BBC Wildlife, and many other magazines and newspapers. He grew up in Louisville, Kentucky. After graduating from the University of Detroit, he taught literature and writing at the University of Connecticut while earning a Ph.D. He lives in West Hartford, Connecticut.

What is an Expedition?

A Madagascar expedition to Marojejy Mountain, 2010. Credit: Christopher J. Raxworthy

Time gets away from me. It’s May and I’ve been slow to post. I have new material that should be in the pipeline soon. I also hope to post two new interviews within the month.

For the interim, you may be interested in a fantastic conference site “What is an Expedition?” which will be hosted by Australian National University in June 2012. In addition to paper abstracts, the site has a spectacular bibliography page which would serve as an excellent reading list for Ph.D prelim students or serious exploration junkies.

Also possibly of interest: “Beyond the Extremes: Contemporary Narratives of Exploration” a panel that poet Ravi Shankar and I organized last week at the University of Hartford. The panel included artists, historians, poets, and anthropologists speaking about the points of connection between exploration and the arts. John Dankosky moderated the panel for his radio show, Where We Live. You can listen to it here.

“The Adventure” by Georg Simmel

In his entire life, Georg Simmel never ventured far from Berlin. He grew up and studied philosophy there. After receiving his Ph.D. at the University of Berlin, he settled in the city. While his peers took up jobs in other university towns around Europe, Simmel got married, published essays, and taught philosophy at the University. He died in Berlin in 1918.

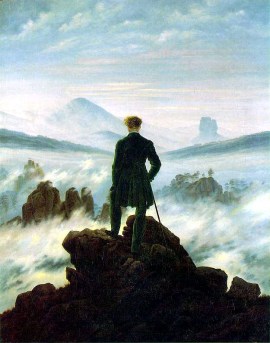

Thus it might seem surprising that Simmel would take up extreme experience as the object of study. Yet this is precisely the goal of his 1911 essay “The Adventure,” which examines the unsettled moments within the arc of an individual life. Within the continuous flow of events that make up the arc of this existence, he writes, there are experiences that seem discontinuous from the rest: moments of intensity cut off from the sensory experiences of the everyday, islands that rise up from the daily events that wash over us and circulate around us.

It is not the investigation of a particular adventure that Simmel is concerned with here, but the architecture of adventure itself. What characterizes it as a psychological phenomenon? What are its attributes as a category of experience?

Simmel concludes that adventures have qualities that are dialectical or paradoxical in nature – elements in tension with each other:

First, the adventure may seem like an island within the flow of a person’s life, but it’s defined by the ocean that swirls around it. This is because Simmel sees adventure as a state of experience rather than a fixed set of events or conditions imposed upon us from the outside. One person’s adventure, after all, might be another person’s day at the laundromat. And since this extreme experience is defined by inner conditions rather than outer ones, the adventure only gains shape according to the particular qualities of the individual. So, as much as an adventure feels extreme and otherworldly, it finds its sharp edges according to the parameters of an individual’s personality.

“It is a foreign body,” writes Simmel, “in our existence which is yet somehow connected with the center.”

Second, adventures are vivid and intense, moments when we feel fully alive. Yet there is also a dreamlike aspect to many of them, an unreal or surreal quality that separates them from the psyche. “The more ‘adventurous’ an adventure…the more ‘dreamlike’ it becomes in our memory. It moves so far away from the center of the ego and the course of life which the ego guides and organizes that we may think of it as something experienced by another person.”

Finally, adventures require intensity of individual action, yet also an extraordinary “passivity” as well: the ability to accept the precariousness of one’s position in the world, to accept the existence of unknown dangers, and yet to carry on as these dangers are known, finite, and surmountable. “Adventure has the gesture of the conqueror, the quick seizure of opportunity….[yet also] the complete self-abandonment to the powers and accidents of the world, which can delight us, but in the same breath can also destroy us.”

Simmel’s inquiry into adventure is interesting because it does not fit neatly into other categories of analysis.

It contrasts, for example, with 19th century scholars, such as Frederick Jackson Turner and Theodore Roosevelt, who viewed hardship and extreme experience as a corrective to the overly civilized life. Adventure, in other words, offered an antidote for the ills of a particular moment in time, the conditions of a discrete historical epoch.

Simmel’s view also contrasts with twentieth century scholars, such as Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell, for whom adventure was not a modern corrective, but a timeless attribute of the human psyche, an archetype or “monomyth,” that all people use to convey meaning irrespective of culture or epoch. The adventure, in other words, is not an event, but a mental device used to impart lessons about society and the natural world.

Simmel’s approach is neither historical nor mythological. Rather, his focus on interior conditions of experience and knowledge sounds a lot like Kant: what we know about the world in and of itself is limited. We should spend our time, then, examining the filters of this experience, the way the mind organizes the world and makes it whole. Simmel also, at times, sounds a lot like Georg Hegel and Johann Fichte: adventure unfolds in the paradoxes and inconsistencies, the theses and antitheses, of extreme experience. Still, Simmel’s discussion of the adventure does not always remain abstract and philosophical. He reveals to the reader, late in the essay, what he sees in his mind when he envisions extreme experience.

It is the love affair. The lover provokes, more than mountain ranges or pack ice, the colors and sharp edges of adventure. The pursuit of a lover is the most dangerous of journeys, one filled with moments of terror and ecstasy. “What is important is the violence of feeling as it alternates between joy and despair, the almost touchable nearness of the daemonic powers which decide between both.” What is achieved in this journey? Not the conquest of a person, the mapping and possession of the beloved. It is the action, rather than the object, that gives life to the adventure. It is the feeling of standing on the precipice, the singular moment when time disappears, when the violence of feeling “becomes great enough to tear life, beyond those materials, completely out of itself.”

Notes:

Read an English translation of The Adventure here.

Thanks to Erik Mueggler for bringing Simmel to my attention.

Jack White’s new song “Love Interruption” expresses many of Simmel’s ideas: action, passivity, and transformation through violence of emotion.

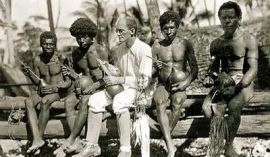

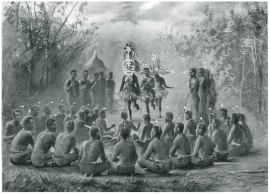

Anthropology of Expeditions: Travel, Visualities, Afterlives

Alfred Cort Haddon's painting of an imagined Malo–Bomai ceremony in pre-contact Credit: Paul Burke Australian National University

Last weekend, I attended a symposium, “Anthropology of Expeditions: Travel, Visualities, Afterlives” at the Bard Graduate Center in New York. I will post some reflections about themes of the conference, starting here with the keynote speech by historian of anthropology, Henrika Kuklick.

In her address “Science as Adventure” Kuklick describes a historical shift in thinking about anthropological fieldwork. In the early 1800s, westerners who ventured into the remote regions of the world were often seen as gofers rather than researchers, rugged collectors that did the bidding of armchair scientists back home. These sedentary scientists did not perceive their distance from the field as a bad thing. Far from it: in their labs and museums, they could pore over specimens and cultural artifacts without the distractions of life on the expedition. In their more controlled habitats, they believed they could consider objects comparatively, objectively, and dispassionately. Thus, distance seemed to offer advantages both physical and methodological: a safe environment and a privileged perspective from which to see species and human cultures without the bias of being on the ground, in the vortex of the new encounter.

By the early twentieth century, Kuklick argues, perceptions of fieldwork began to change. The New Imperialism of the late 1800s brought huge swaths of Africa and Asia under colonial control, making them more accessible to field scientists. The rise of disciplines such as public health and tropical medicine also gave new impetus to the human sciences conducted in remote places. Finally the meaning of first-hand fieldwork itself had started to evolve. No longer did the field represent a place of bias and distortion, but as a stage for adventure. In adventure, the explorer-scientists could show their passion for science, a passion great enough to risk sickness and death, and thereby enhance their reputation for trustworthiness in the process. In showing an adventurous spirit, the pith-helmeted field scientist’s credibility was revealed, not diminished. “It is because they act heroically, Kuklick writes “that their testimonials can be believed.” Kuklick presents a number of examples of this new authority of adventure within the work of anthropologists, particularly in the writings of Bronisław Malinowski, who studied native peoples of Australia and the Western Pacific.

Yet it is not clear to me that these examples are as representative as Kuklick claims. Yes, we can find prominent armchair scientists in the nineteenth century as Kuklick suggests, men such as Richard Owen and Georges Cuvier who were happy to do science from the confines of the museum. But we can also find plenty of counter examples: explorer-scientists such as Alexander von Humboldt, Charles Darwin, and John Tyndall who were not just tolerated, but celebrated, for their rugged fieldwork.

Indeed, adventure had become something of a fetish by the mid 1800s, affecting not only scientists but legions of western writers, artists, and intellectuals. This was, after all, an era still enthralled by Romanticism, a movement that celebrated the individual’s confrontation with nature as an essential component of truth seeking.

Conversely, the twentieth century is not quite the adventure-junkie paradise that Kuklick suggests. True, the early 1900s had a number of adventurous anthropologists, as Kuklick persuasively documents, but it also had plenty of scientists who lamented adventure as a distraction from serious field work. Beginning with the International Polar Year of 1882-3, western scientists sought to distance themselves with expeditions based on pure adventure. It was for this reason that the American Geographical Society tried to make its organization more rigorous at the turn of the twentieth century. Even the father of American anthropology, Franz Boas, believed that adventure could be taken too far. “We must not forget that the explorer is not expected merely to travel from one point to another,” Boaz wrote, “but that we must expect him also to see and to observe things worth seeing.”

In short, western scholars have been debating the meaning of expeditionary fieldwork for at least 250 years. Whether one views it as the peripheral, or the central, event of scientific discovery probably has more to do with issues of personality, individual opportunities, and disciplinary training than shifts in the scientific zeitgeist. If it does express a shift, as Kuklick suggests, I think it’s more likely to be confined to the discipline of anthropology. As for the meaning of fieldwork outside anthropology, the patterns are more difficult to see.

Remembering the Race to the South Pole 100 Years Ago

British Antarctica expedition at South Pole in 1912 standing near Roald Amundsen's tent. From left to right: Robert Scott, Titus Oates, Edward Wilson, and Edgar Evans. Credit: The Australian.

One hundred years ago this winter, two polar expeditions disembarked on the northern edges of the Ross Ice Shelf in Antarctica with the goal of reaching the South Pole. One party, led by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, reached 90º S on 14 December 1911. The second party, led by British officer Robert Falcon Scott, arrived a month later on 17 January 1912. Amundsen and his men returned to announce their victory, while Scott and his party of four men died on the trek back, succumbing to starvation and cold.

The meaning of Antarctic exploration has been cast in the forge of the Scott-Amundsen race ever since. There are good reasons for this. The event was significant geographically: representing the attempt to erase the last, substantive terra incognita from the modern world. It was also important politically: highlighting the competition between different Western powers on the eve of the Great War. For historians, it offered a way to demarcate the eras of exploration: signaling the key event in Antarctica’s “Heroic Age” and capping the end of a century of intense polar exploration. Lastly, it offered a great story: in the great race to the South Pole, writers have found heroes, villains, experts, and bumblers toiling on a landscape both severe and sublime.

Yet Scott and Amundsen were not the first to understand Antarctica’s power as a canvas of the imagination. Three hundred and forty years before Robert Scott and Roald Amundsen raced across Antarctica, this southern world filled the mind of Abraham Ortelius as he crafted his magisterial atlas, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (The Theater of the World). Terra Australis, as Antarctica was then called, sprawled over the page of Ortelius’s world map. Its ragged coastline reached South America and brushed up against the shores of New Guinea and the Spice Islands. It was a polar continent, but it was also a tropical one, crossing the Tropic of Capricorn in the western Pacific to come within twenty degrees of the equator. Even accounting for the distortions of map projection, Terra Australis was a vast place, dwarfing the other continents of the world.

Despite its imposing form, however, Terra Australis was built on fragile empirical foundations, something that Ortelius knew when he published the atlas. The title page of Theatrum, which depicts the continents in allegorical form as goddesses, expresses his ambivalence about the southern continent. At the top of the page, Europe sits on her throne, while Asia and Africa, semi-clothed and semi-barbarous, stand beneath her. At the bottom of the page reclines America the cannibal, naked except for her loin cloth. Terra Australis stands next to her, a figure incompletely revealed in a block of marble, a continent glimpsed but still unknown.

In seeing explorers as sculptors, Ortelius was probably thinking about the sculptors of his day, artists like Michelangelo who had been moved by the spirit of Neo-Platonism and who saw it as their task to “liberate the figure imprisoned in marble.” From this perspective, the congruence between the artist and explorer was easy to see: they were both the messengers of objective truth, vectors of knowledge rather than its creators. Terra Australis waited for the explorer to chisel her out of the hard whiteness of high latitudes, revealing her true form to the world.

Yet Ortelius’s allegory of Antarctica carries different meanings today, a time when artists do not often describe their work as the liberation of perfect forms or pre-existing ideas, but as creative and subjective acts. If sculptors fashion their figures rather than reveal them, the half-rendered figure of Terra Australis has a different message. In order to bring this continent to life, the allegory suggests, the explorer must envision it and give it shape. Its storms, mountains, and coastlines – its very identity as a place – emerge as the vision of its creator, subject to ideas, expectations, and beliefs. The marble is not silent, of course. The continent of Antarctica, like every artistic medium, carries its own powerful agency (as Scott and his party would attest) imposing its own limits on the form revealed.

Had Ortelius been alive in 1912, the year of Scott and Amundsen’s great race to the South Pole, I suspect he would have felt the impulse to finish his Antarctic goddess, to give the continent her final unchanging and eternal form, installing her in his allegorical pantheon like a stone deity in the temple of Olympus. Yet the continent of Antarctica is not so fixed. While its coastlines and topography are now stable enough to secure within the pages of the modern Atlas, its meanings are not.