Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationArchive for Space

Let’s Get Geophysical

As some of you know, we are in the midst of the International Polar Year (IPY) 2007-2009, a global program to coordinate research in the Arctic and Antarctic. This IPY follows three earlier ones: in 1883-1884, 1932-33, and 1957-1958 (which was, technically, the International Geophysical Year IGY). The first IPY was the brainchild of Carl Weyprecht, an Austrian explorer who had grown tired of watching explorers race into the Arctic on bids to attain “Farthest North,” lose their toes to frostbite, then return home with pockets empty.

Carl Weyprecht

The “Race for the Poles” was, Weyprecht realized, a race but little else. As such, it was at odds with the needs of polar research, which required observers to stay in one place long enough to take note of what they were seeing, record measurements, and collect data. Only in this way would scientists begin to figure out how the polar regions functioned holistically, and then, how they influenced the rest of the world, particularly global weather and climates.

For over a century, science and transnational collaboration have been the twin pillars of the IPY philosophy. In combining them, scientists hoped, they could uncover the mysteries of the polar regions, all the while avoiding the need to subject their projects to the demands of the glory-hungry explorers and jingoistic leaders.

Yes, well, it was a lovely idea. In truth none of the IPYs were free from megalomaniacs (on sledges or in political office). During the first IPY, the United States outpost at Lady Franklin Bay, under the command of Adolphus Greely, dutifully collected research.

The Greely Party in 1881

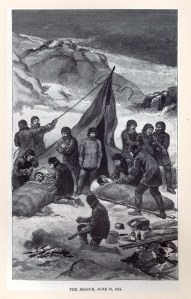

That is, until, Greely saw an opportunity to beat the record of “farthest north” held by the British. Two months of sledging and 600 miles later, Greely’s party established a new “farthest north” record of 83°24,′ exactly three nautical miles farther than the one set by the Nares Expedition in 1875. Science and latitude records were forgotten, though, with the expedition’s demise from cold and starvation. The failure of relief ships to reach Greely resulted in the deaths of most of his party. Nor did the spirit of the IPY carry on after the expedition’s rescue. The impressive pile of data collected by stations all over the Arctic could not compete with reports of Greely’s incompetence, evidence of cannibalism, and the execution of a crew member for stealing food.

The Greely Party in 1884

Fifty years later, an international meteorological congress tried to resurrect the idea of scientific collaboration with IPY-2, which took a new set of questions about magnetism, the aurora, and radio science, to the poles. Yet coming as it did in 1932, in the depths of the Great Depression, IPY-2 fell short when the money ran out.

The IGY of 1957-1958, conceived in the midst of the Cold War, seemed just the kind of feel-good, collaborative effort needed to reduce tensions between East and West. Unfortunately the first offspring of IGY was Sputnik. As the tiny satellite beeped its way over the Western hemisphere, it brought tears to the eyes of Russians, and visions of nuclear-tipped ICBMs to anxious Americans.

Despite talk of science and collaboration, then, the legacy of the IPYs has featured much of the vain-glorious and nationalistic pap that Weyprecht had been trying so earnestly to avoid. What then, can we hope to achieve in IPY-4? If my experience at the IPY-sponsored North By Degree conference is any indication, I think the ultimate benefit of getting people together is, well, getting people together. No one can offer a guarantee of future accomplishments. Most IPY subjects and discussions are too wonky to make good headlines. But ultimately the international IPY is a form of social communion, a way of building relationships. We had tense moments in Philadelphia – but we all stayed in the room – and continued to talk and argue about our positions for the extent of the conference. It is from this messy back and forth, I think, that real collaborative projects grow.

Famous Falling Objects

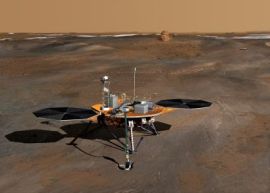

An update on Saturday’s post: The Mars Phoenix Lander successfully touched down on Sunday and has started unpacking its bags. Like any good tourist, it has started taking pictures of itself.

It’s also taken some lovely shots of the polar surface. They show a delicate pattern of polygons etched into the dirt, strongly suggesting the presence of water.

Michel Fournier has had less luck on his quest to become the first human meteor. On Tuesday, his crew began filling up the massive balloon that would be used to carry him to 130,000 ft. But for unknown reasons, the balloon decided to leave without him. After shooting upwards, it began to lose helium, eventually plummeting to earth, tearing itself to shreds on the way down.

I am not sad to see this mission fail. As I mentioned in my earlier post, Fournier’s seems like a project better designed for spectacle than science (though, as a student of the history of science, I admit the line is blurry). Fournier gets points for bravery. And this kind of jump had serious application once, in the early days of space flight, when no one knew what would happen to astronauts bailing out at high-altitude. But at 64, Fournier hardly offers science the best physiological model of a 35 year old astronaut. More to the point, for this sort of testing has been done before. Fifty years ago, Joseph Kittinger set a jump record of 96, 760 ft as part of the Man High I Project. In 1960, he set the altitude jump record that still stands: 102, 800 ft. Now, Fournier will have to decide if he really wants to continue with “Le Grand Saut,” as they call it in French, or “The Man Seriously High Project” in the lower 48.

Col. Joseph Kittinger’s seriously high jump in 1960

Touchdown! Mars Phoenix Lander

Touchdown! The Mars Phoenix Lander transmitted this image a few minutes ago. Congratulations to the University of Arizona. Go Wildcats. See yesterday’s post for more.

Mars Phoenix Mission

Tomorrow I’ll be watching two flying objects: the Phoenix Lander, a $420 million dollar spacecraft descending towards the polar plains of Mars, and Michael Fournier, a 64-year-old Frenchman who will be hurtling towards the bucolic pastures of Saskatchewan.

The Phoenix Lander comes equipped with a robotic arm camera, surface stereo imager, and thermal and evolved-gas analyzer. Fournier comes equipped with a space suit lined with wool underwear. If all goes well, both Lander and Fournier will deploy parachutes. The Mars Lander will spend its post-touchdown period testing the Martian soil to see whether water exists near the Martian poles and if it could support life. Fournier will spend his post jump moments speaking to the press and thanking his supporters. Fournier’s jump, if successful, will establish a record for highest human balloon flight and break altitude, speed, and time records for freefall. Not that this makes any difference to Fournier I guess:

“It’s not a question of the world records,” Fournier wrote via e-mail through an interpreter on Friday from his base in North Battleford, Saskatchewan. “What is important are what the results from the jump will bring to the safety of the conquest of space. However, the main question that is being asked today by all scientists is, can a man survive when crossing the sound barrier?”

Whether someone can break the sound barrier without becoming a human flank steak, is, I guess, a question that burns in the mind of Michel Fournier. But it is not “the main question that is being asked today by all scientists.” If Fournier really believes this is about science and not about personal glory, wouldn’t it be simpler (and safer) to send a crash-test dummy up instead? After all we have machines nowadays that measure pressure and temperature and others, called transmitters and receivers, that can relay this sort of information to earth. Maybe this was cutting edge technology back in the age of the V-2, but its pretty routine today. Oh, and no one dies.

Chasing the Moon

Time Magazine writes in a online special report about NASA’s current “Constellation Program,” a plan to send astronauts back to the Moon in preparation for a Mars mission in 2020. One of NASA’s first steps will be to launch the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) in Fall 2008, a craft that will be able to make detailed, wide-ranging surveys of the lunar surface. I wonder how long it will take Google Moon to get hold of these surveys. I admit, the LRO piece of this mission seems very cool, but I still have serious doubts about the broader mission as I have written in an earlier post. The Time report doesn’t talk much about the utility of the mission, or its possible negative impact on space science, but it does talk about the daunting budgetary hurdles NASA faces for the next fifteen years:

It’s unlikely, then, that any future President will make manned lunar exploration a real priority. Which means inadequate funding for NASA and a tough bind for the agency’s administrator, Michael Griffin. “If the President says you’re going to the moon with this amount of money,” says [Astronaut Alan] Bean, now 76 and an artist in Houston, “you’d better say yes, because if you don’t you aren’t going to have a job anymore.” In effect, he says, the space agency must go through the motions of building hardware until the money runs out, knowing it won’t be enough to make it to the moon.

So here’s the question: when the funding does fall short on the Constellation Program at some point over the next decade, what’s Plan B? What will we plan to do with these jacked-up Ares rockets, Orion crew exploration vehicle, etc? And in the interim, how many science projects will be the “fat” that gets trimmed in order to put humans on Mars? Will the expense justify the money spent to send them there? Spirit and Opportunity seem to be doing a terrific job on Mars as we speak, and they don’t require food, water, back pay, or golf clubs.