Time to Eat the Dogs

A Podcast About Science, History, and ExplorationArchive for Popular Culture

Polar Hoaxes and Lost Worlds

A century ago this week Robert Peary and Frederick Cook locked horns in the “The North Pole Controversy,” an epic media battle that dominated news on both sides of the Atlantic for months. For readers it became a scandalous and impossibly compelling story, a post-Victorian Jon vs. Kate with furs and dogs.

John Tierney

John Tierney took up the story in the New York Times yesterday morning. To Tierney’s credit, he avoids the temptation to spend his entire column regaling the reader with evidence of Peary or Cook’s rightful attainment of the Pole. (He does take a position: neither man made it).

Instead he takes an interesting behavioral, rather than historical, approach to the question: why do the supporters of both explorers defend their man against all reasonable arguments? The answer, he argues, is that they become psychologically (perhaps neurochemically) committed to their candidate in a manner that is hard to alter. The use of the word “candidate” here is intentional since Tierney reports that this phenomenon is well measured in people supporting politicians and political parties.

Map of the "lost world" of Mount Bosavi

Also reported yesterday was the discovery of a “lost world” in Papau New Guinea. A team of scientists (big discoveries always follow sentences that begin with ”A team of scientists…”) discovered a unique, pristine ecosystem in the crater of Mount Bosavi. The team found more than forty new species, including the world’s smallest parrot, the world’s largest rat, and a herd of grazing brontosauruses. (I’m making up the rat part).

The use of ‘Lost World’ is an interesting way to describe this ecosystem not simply because it conjures images of Jurassic Park, Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1912 novel of the same name, and a whole genre of early twentieth-century adventure books, but because it’s not an obvious (and therefore not an unconscious) description of Mount Bosavi.

Accounts of the volcano, its geographical and biogeographical riches, have been appearing for forty years in academic journal (see for example Records of the South Australian Museum 15 (1965): 695-6; Mammals of New Guinea (1990): 236) and even further back in popular literature. Jack Hides and other Australians were writing about the Mount Bosavi in the 1930s.

Bosavi Woolly Rat, photo credit: Jonny Keeling

But “Lost World” sounds better than “Relatively Unknown Ecosystem” especially if it’s timed to coincide with a 3-part BBC Special on the expedition (titled “Lost Land of the Volcano”). Perhaps these are the necessary evils of science reporting in the digital age, a realm in which writers have two or three seconds to convey meaning and produce interest. Maybe these are the white lies required to raise the profile of meaningful and interesting projects. “Lost Land of the Volcano” pulled in 4.1 million viewers last night, an 18% share. Maybe the title of this post should be “Cow-Sized Rat Kills Cannibal, Saves Scientist.”

Where No ENFP Has Gone Before, Part II

(For Part I, go here)

I first took the Myers Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) when I was a junior in high school. This was a good time to take it since, like most sixteen-year-olds, I was self-absorbed enough to think I should spend more time trying to figure myself out.

The test labeled me as an ENTP: Extroversion, Intuition, Thinking, Perceiving.

I was a clear extrovert, someone who Jung describes as gaining energy from the world around them, or in my case, trying to set fire to the world around them. Introverts like Jung find energy through reflection. Thinking first, acting second. An interesting idea.

I also tested strongly intuitive, or as the MBTI would observe, I gathered information as concepts and abstract patterns rather than as concrete, immediate facts available to the senses.

One axiom of the MBTI is that personality types are stable, more or less. As this idea goes, the psyche sets up basic patterns of gathering, interpreting, and acting on information quite early, by age three or four.

Yet critics of the MBTI such as Paul Matthews point out that people who take the test often get different answers. My testing history confirms this as well. In high school, the MBTI tagged me as a thinker rather than feeler, deciding issues on logical and consistent premises.

When I took the test again last week, I had swung over to the feeling side of the spectrum, making decisions based upon personal association or empathy more than general principles. That a person’s psychological type seems squishy, mutable over time, is one of many criticisms leveled at the MBTI, one that challenges its claim to measure meaningful psychological differences.

Still, my MBTI evaluation has been stable other than that, particularly in the final category of perceiving/judging which evaluates how people process information. Strongly judging individuals tend to like settling matters and, as a result, gather information in order to make decisions and tie up loose ends.

Those with strong perceiving tendencies (of which I am one) gather information like rodents in November, amassing it without end. Perceivers are the hoarders of ideas, stowing and revising them even though it keeps things unsettled. They have messy desks.

Driving on Rt 6 in Wellfleet last week, my wife Michele (an INFJ) wondered how her students might type characters in her lit courses. Ahab would have to be an INTJ. The Great Gatsby? ESFP I think.

The conversation brought me back to a post I wrote last year about The Explorer Type. At the time, I was thinking about how certain explorers, such as Roy Chapman Andrews and Louis Leakey, took on similar cultural personae: popular outsiders who contributed to, but were not a part of, the academic establishment.

Was there something deeper here? A psychological type that lay behind the public persona? The ENTP personality type (Extrovert, Intuitive, Thinking, Perceiving) is often labeled “The Inventor-Explorer.” Other analyses of Myers-Briggs tag INTP (Introvert, Intuitive, Thinking, Perceving) as the rightful home of this type. Yet what spotty data exists on this subject shows that real explorers, such Chuck Yeager and Alan Shepard, test as ISTPs (Introvert, Sensing, Thinking, Perceiving).

Alan Shepard

Then again, test pilots and astronauts offer a narrow field of explorers. Reading Goethe and ranging over the mountains of South America, would Alexander von Humboldt have been an ISTP? Never. An ENTP if ever there was one.

Nor should the military discipline and technical demands of modern spaceflight necessarily point to controlled, process-oriented types such as ISTPs. The world’s most famous astronaut is a confirmed ENFP.

An ENFP seeks out new worlds.

Take a quick MBTI assessment here.

Type profiles are available here.

Other posts on exploration and personality:

Where No ENFP Has Gone Before, Part I

Myers-Briggs personality assessments are sprouting up everywhere on Facebook this week. For those who don’t know what this is, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is the most widely used personality profile in the United States, a favorite tool of career planners, team-builders, and guidance counselors.

Isabel Briggs Myers

Brain child of Katherine Briggs and her daughter Isabel Myers, the MBTI divides the human psyche in four separate areas, each one of which has two different tendencies or dichotomies:

Extraverion (E)/Introversion (I)

Intuition (N)/Sensation (S)

Thinking (T) /Feeling (F)

Judging (J) /Perceiving (P)

There is nothing obvious about these psychic divisions. In truth, the categories of the MBTI were long in the making. In the early 1920s, Briggs was experimenting with a number of different categories for explaining the diversity of human behavior. More specifically, she was interested in explaining the strange, unBriggs-like behavior of her new son-in-law.

Then Myers read Carl Jung’s Psychological Types in 1923 and psychometric light bulbs started to go off in her head. Jung’s system seemed perfectly suited for creating a system of personality profiles. This is probably because Jung had his own strange in-law to explain, former mentor and father-figure Sigmund Freud.

Carl Jung (lower right) and Sigmund Freud (lower left), 1908

Freud, Jung observed, gained energy by focusing on the outside world, a process that Jung called extraversion. Jung, however, was different. He found succor looking inward. (As a boy Jung spent his days writing secret messages to a mannequin carved on the end of his ruler). These were not neuroses, he thought, as much as they were different expressions of personality (though Jung does make one wonder).

Indeed, Jung felt that the spectrum of introversion and extraversion expressed a key dichotomy in western thought, one that dated back to the different approaches of Plato, who usually sought truth inwardly through the world of ideas, and Aristotle, who looked for reality in the phenomena of the world around him.

All of this is to say that the roots of the MBTI go deep. By the 1940s, Myers had expanded on Jung’s types and established a test that could be used for commercial application. Since then the MBTI has rocketed into mainstream culture, used to profile everyone from religious seminarians to astronauts.

Next Post: MBTI and the Explorer Type

Blue Hole

In 1989, I accepted a two-year job teaching English in Egypt. The school offered $50/month and a place to live. The city of Cairo offered everything else, a theater of sound and spectacle, and a small part for me to play alongside seventeen million other residents, all acting out their lives on a stage twice as crowded as Tokyo. None of this felt comfortable.

Growing up in Maine, I was nurtured in a world of careful distances, social and spatial. This was exactly the point, I guess, in going to Cairo: to push beyond the boundaries of comfort, to come up against the hard-to-digest, to learn truths not accessible in the coffee shops of Portland or the classrooms of Boston.

Still, everyone has limits. When I reached mine, we, my roommates Joe and Alex (also American teachers), would head for Dahab, a dusty Bedouin village on the East coast of the Sinai Peninsula – about as remote and sparsely populated a place as you could reach from Cairo on our salary.

Dahab was the anti-Cairo, a place of self-indulgence and open spaces. It was our refuge from work in the city, a world of scattered huts and ex-pat dive shops, a place that always smelled of grilled fish, motor oil, and hashish, where daily calls to prayer had to compete with Sinead O’Conner’s Nothing Compares 2 U.

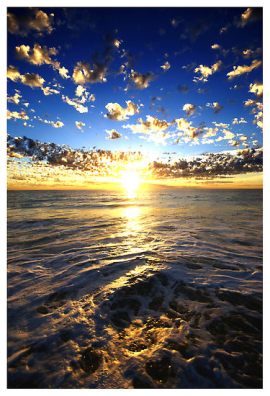

We spent most of our time there underwater. When we weren’t snorkeling, we were reading, or writing, or drinking warm beer in the bars that lined the beach. One time we arranged a ride to the Blue Hole, a coral lagoon just outside of town.

The Blue Hole, Eastern Coast of the Sinai Peninsula

From the front seat of a Fiat, the Blue Hole did not look like much. It was much like the rest of the Sinai coast, arid, brown, and rocky, devoid of life. Two things stuck out though: a giant gouge of blue water in the long shallow shelf of coral that hugged the shore, and a set of improvised memorials for dead divers on the rocky beach.

I put on my snorkel and flippers and swam towards the gouge, the tip of which was only a few feet from the shore. What I saw there made me flinch: a vertical wall of coral that dropped straight down, hundreds of feet, out of sight into blackness. The wall extended in a rough circle the size of a stadium.

Beneath me were schools of fish, angel and butterfly fish, clown fish, and beneath them, anemone fish and coral groupers, and beneath them, other fish that I couldn’t see clearly because they were so far away.

To swim in the Blue Hole was to hover at the top of a giant underwater atrium, the walls of which were alive and moving with color, a column with no bottom, no reference points except void and sky. It was unnerving and disorienting, an effect that became more pronounced the further I swam away from shore and towards the outer edge of the reef. There, I felt as if I was swimming through an electric current. My limbs felt twitchy and my heart raced. I felt exhilarated and ebullient and, strangely enough, like I was about to die.

Joe and Alex were also deeply moved. We spoke about it back in Dahab, wrote about it, continued talking about it back in Cairo. It entered our discussion of books — The Razor’s Edge, On Human Bondage, Steppenwolf, Siddhartha, and The Fountainhead — , which we swapped back and forth, the young man’s library of self-discovery.

Swimming into the Blue Hole, “the abyss” as we now called it, became a metaphor for this quest of meaning, a measure of authentic experience. Real change, it seemed to us, had to evoke fear and present dangers. It could not be controlled and would always exact something as payment. After I started graduate school in the 1990s, I laughed when I discovered that a long tradition of Romantic self-discoverers had already thought through this sort of experience and named it “the sublime.” We were only 250 years behind Edmund Burke. At twenty-three, I had the hubris to think it was something new.

Assuaging the Waters, John Martin, 1840

But I didn’t care and don’t care much now. If the questions were not historically unique, the experience was, a moment seared into our collective memory. It still is. And the questions raised by Dahab still linger: does authentic, change-provoking, experience always come through such electrifying moments? Does it have to produce terror and exaltation? Or is this a young person’s enlightenment, only one of many paths to discovery? Perhaps are there different, more incremental experiences that etch change more indelibly on the psyche: a decade of grading papers, reading bedtime stories, tying shoes, changing diapers.

Twenty years after Dahab, I have different questions. What are the elements that most affect us when we travel? People buy guide books and travelogues and maps on the presumption that places have qualities that are important, durable, and thought-provoking, that a meaningful tour of New York City requires stops to the Statue of Liberty, Nathans, and Broadway. Historians tend to see the larger forces at work: our trip to Dahab came only seven years after Israel returned the Sinai to Egypt – and was only a few months removed from the beginning of the First Gulf War.

Yet maybe these features of landscape, culture, and politics are not always so important – the catalysts at best to a process of change that is latent, subliminal, primed for expression. Perhaps my moments of discovery — Boston 1988, Dahab 1990, Copenhagen 2009 — are about people rather than places. Perhaps Joe and Alex were the key features of this Sinai landscape, not deserts or coral reefs. Or maybe the peoples, places, and things of any trip always take on changing levels of importance, values of meaning that, like schools of fish, are always in flux.

News of the Expedition: Absolutely Free

Terra Nova, British Antarctic Expedition, 1910. Courtesy of Freeze Frame.

Sitting at the long desk of an archive, wearing cotton gloves, reading old letters on the verge of turning to powder; this is about as good as it gets for a historian. Yet more and more of my research takes place elsewhere, now on my laptop mostly, looking at materials that have been scanned and displayed online.

Frank Luther Mott, 1951

Things have changed. When Frank Luther Mott began researching his comprehensive History of American Magazines in the 1920s, he had to track down a paper copy of each periodical in libraries scattered across the country. Many of these publications, printed on acidic paper, were already falling apart.

By 1941, University Microfilms (now ProQuest) began photographing American periodicals, making them available as reels of microfilm. By the time the project was complete, UM had a collection of 1100 American periodicals spanning the years from 1741-1900.

This was the state of things when I began my dissertation research in the late 1990s. When I wanted to find out what was being written about Arctic exploration in the press, I consulted a set of books, the 19th century Poole’s Guide to Periodical Literature, which gave titles and citations of popular literature by subject. Then I would drive to Chicago (from Madison WI) with my list of citations to track down the articles on the spools of microfilm housed at University of Chicago and Loyola University.

Now Poole’s has been turned into a digital database that can be searched online. The American Periodical Series has also been scanned, and, because of character recognition software, can be searched down to the level of single words. Where I spent hours tracking down a handful of articles indexed by Pooles by title and subject, a “full text” search of the American Periodical Series online yields thousands of results, all of which are instantly readable, printable, and download-able from the comfort of my front porch.

Less romantic than heading to the archive, I understand, but infinitely more powerful and convenient.

Still, the conversion to digital has its downside. Poole’s and the American Periodical Series have been digitized by private companies which sell subscriptions to their databases at a hefty price. The result is that that Research I universities like Yale have extraordinary access, whereas smaller universities like the University of Hartford make due with less. Many of my European friends — working at institutions with little money for databases — go without.

The good news is that freely available digital resources are growing in breadth and depth. While the American Periodical Series remains a subscription-service, students of American history can access the 3.8 million pages of 19th century books and periodicals in the Making of America database developed by the University of Michigan. You can also find close to a million pages of material at the Making of America sister site at the Cornell University. Serious free research also extends to the Library of Congress’s 1 million pages of newspaper text at Chronicling America.

These are general databases for American history. Students of more specialized topics, such as the history of exploration, can also find free riches online. In addition to the links at the right, you might also want to check out:

Harvard University Library’s Expedition and Discoveries

A site of highlights and citations from dozens of 19th century expeditions fielded by Harvard and other organizations.

The Scott Polar Research Institute’s collection of polar images from 1845-1982, searchable by date, expedition, photographer, or subject matter.

Mountaineering and Polar Collection

The National Library of Scotland’s site for important historical expeditions, from the ascent of Mt. Blanc to investigations of Antarctica.