On Monday 31 January, PBS will air a documentary called “The Greely Expedition” on American Experience. I served as an advisor on the project. Organized in conjunction with the first International Polar Year, the Greely Expedition was supposed to represent a new kind of Arctic exploration, one focused on international, collaborative science rather than pell mell dashes to the North Pole. In the end, however, the expedition signaled the end of serious collaboration between Arctic explorers and scientists for decades. Here’s an excerpt from my Greely chapter in The Coldest Crucible: Arctic Exploration and American Culture.

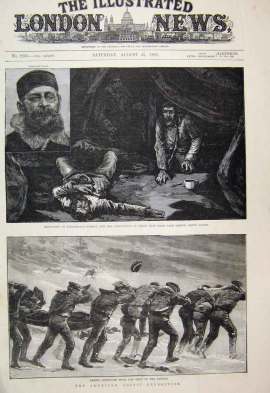

In June 1884, Commander Winfield Scott Schley cruised the waters of Smith Sound searching for Adolphus Greely and his missing party of American explorers. Greely had been in the Arctic for three years, establishing a scientific station at Lady Franklin Bay as a part of the International Polar Year. Two attempts to relieve Greely, in 1882 and 1883, had failed and Schley’s expedition represented the last reasonable chance of finding the Greely party alive. When one of Schley’s men discovered a note from Greely giving his location at Cape Sabine, Schley sent John Colwell and a small party to find him. Arriving at the site, Colwell found Greely along with six other emaciated men, survivors of the original party of twenty-five. In his narrative of the rescue, Schley described the scene:

Colwell crawled in [the tent] and took him by the hand, saying to him, “Greely, is this you?” “Yes,” said Greely in a faint, broken voice, hesitating and shuffling with his words, “Yes – seven of us left – here we are – dying – like men. Did what I came to do – beat the best record.” Then he fell back exhausted.[i]

Schley was not on the beach himself and relied upon the reports of his men to piece together events. Yet his narrative, published almost a year after the return of the survivors, soon gained authority as a true-life account of the dramatic rescue. The New York Herald excerpted it liberally in its reports about the expedition. Later reminiscences, such as Munsey’s Magazine’s 1895 account of the expedition, presented the scene exactly as it had appeared in Schley’s narrative. Even David L. Brainard, one of the seven survivors of the Greely party, used Schley’s dialogue word for word in his 1929 account of the expedition, as well as in a more candid narrative that he published in 1940. Yet others on the beach recalled the meeting differently. One member of the rescue party reported that Greely first asked him “if we were Englishmen.” Another remembers Greely chastising them. “If we’ve got to starve . . . we can starve without your help . . . we were dying peacefully until you came.” Maurice Connell, one of Greely’s men, was unconscious at the time of the rescue. Yet for him the published account of Greely’s words did not ring true. In the margins of Schley’s book he wrote: “‘Give us something to eat!’ more probably.”[ii]

Whether or not Greely, delirious and close to death, uttered his pithy remarks is unclear. What is clear is that the scene Schley described offered a far more respectable image of Greely and his party than the ones that circulated for months in the popular press upon Greely’s return. Immediately after the return of Schley’s rescue expedition, the New York Times, the Chicago Tribune, and other papers deluged readers with lurid stories about the Greely party’s demise on Cape Sabine. They uncovered Greely’s execution of a man for stealing food. They reported on rumors of cannibalism among the party and discussed charges by Greely’s men that he was inept as a commander. Schley’s account did not erase the impact of these revelations, but arriving in the wake of the reports, offered a means of capping the well of controversy, as its extensive use later suggests.

The controversy that engulfed Greely after his return eclipsed his expedition’s scientific work. Billed as the most ambitious research mission ever sent into the Arctic, Greely’s expedition marked instead the end of serious collaboration between scientists and Arctic explorers in the nineteenth century. In the decades to follow, explorers occasionally promoted their voyages as research expeditions, but their words had little bearing upon their expeditions or campaigns. New patrons of Arctic exploration freed explorers from having to appeal to the scientific community to raise funds or lobby Congress. From the point of view of scientists, Greely and other explorers had abandoned their research missions in order to give allegiance to new masters, private patrons and press moguls who cared little about Arctic science. Schley’s account of the rescue only underscored the point. Greely declared to Colwell that he “did what I came to do – beat the best record,” but he had not entered the Arctic to do anything of the kind. In fact, organizers of the Greely expedition had hoped quite the opposite: that Greely and his men would turn their backs on dangerous and irrelevant dashes to the North Pole, focus on methodical research, and embrace the collaborative spirit of the International Polar Year. To his credit, Greely carried out much of this research at first, but he eventually turned his attention to the geographical dashes so disapproved of by international organizers. Greely’s words on Cape Sabine, true or apocryphal, only confirmed suspicions that science had also been a casualty of his expedition.

The claim that the Greely expedition marked the end of explorers’ serious collaboration with the scientists stands at odds with most historical accounts. Because Greely brought back the most comprehensive and systematic set of observations ever produced by Americans in the Arctic, historians have often held it up as a sign that U.S. scientific exploration had come of age. For historian of science A. Hunter Dupree, the Greely expedition “laid the groundwork for a really scientific interest in Arctic and Antarctic problems.”The wealth of data collected by Greely and his men has led William Barr to revisit the events of the expedition in hopes of illustrating its scientific importance. Expedition historian A. L. Todd agrees, calling Greely’s official narrative “one of the most important source books of arctic data available to the world of science.” Focused on quality of expedition data, however, these works leave unexamined the reactions of scientists, press, and public back home. Fixing our attention here, we see a different picture emerge: a diminished role for science in Arctic exploration, a waning collaboration between explorers and researchers, and a decline of scientific rhetoric in expeditionary campaigns.[iii]

The reasons for this change extend beyond the expedition. Greely and his rescuers may have sown the seeds of controversy by their actions in the Arctic, but these actions only bloomed into scandal because of important cultural and institutional changes back home. That science fell victim to scandal after Greely’s return reflected a new trend in newspaper journalism that put a premium on critical, often sensational, reporting. This was a far cry from the 1850s, when reporters generally avoided controversy in their attempts to portray Arctic explorers as American heroes. By the 1880s, however, writers proved far more willing, even eager, to expose expedition scandals even when it came at explorers’ expense.

The estrangement of explorers and scientists also grew out of changes in the patronage of Arctic exploration. Whereas Henry Grinnell had encouraged his explorers to campaign as a way of raising funds and creating broad coalitions among scientists and the public, the deep pockets of new patrons such as the New York Herald made such actions unnecessary. Flush with funds and backed by promotional power of their patrons, explorers had little need to campaign. Greely took his orders from the Army Signal Corps, not the popular press, but many of the effects were the same. With his expedition already organized and underwritten by the Corps, Greely felt no incentive to write, lecture, or rub elbows with scientists or other groups in the months before his departure. As a result, Greely established few of the personal bonds with scientists and others that had so benefitted Elisha Kane and helped to insulate him from his critics…

[i]. Two of the twenty-five members of the expedition were native Greenlanders, Jens Edward and Thorlip Frederick Christiansen. Quotation is from W. S. Schley, The Rescue of Greely (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1886), 222.

[ii]. “The Rescue of Greely,” New York Herald,” 26 March 1885; Frank Lewis Ford, “The Heroes of the Icy North,” Munsey’s Magazine 14 (1895): 296; David L. Brainard, The Outpost of the Lost: An Arctic Adventure (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1929), 312; Brainard, Six Came Back: The Arctic Adventures of David L. Brainard (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1940), 301; “if we were Englishmen . . .” comes from Charles Harlow, “Greely at Cape Sabine,” Century Magazine (undated) in Adolphus Washington Greely Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.. “If we’ve got to starve . . .” is from Frank B. Copley, “The Will to Live,” American Magazine, February (1911): 502-3. “‘Give us something to eat!’” comes from newspaper clipping “Sergeant Connell”, 31 May 1885, Box 74, Greely Papers, Library of Congress.

[iii]. A. Hunter Dupree, Science in the Federal Government (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1957), 193; William Barr, The Expeditions of the First International Polar Year, 1882-83 (Calgary: University of Calgary, 1985); A. L. Todd, Abandoned (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1961).

Thank you for bringing this fascinating but tragic Expedition back in front of the public.

Anyone wanting some insights into what the final stages of the Franklin Expedition MAY have been like would do well to study the Greeley experience. The gradual transition from hunting and fishing to cannibalism is especially sad.