The Joy of Cooking has many merits: simplicity, comprehensiveness, ease of use. It doesn’t put on airs. My 1967 copy includes a diagram for skinning squirrel along with preparations for raccoon, woodchuck, and wild boar.

The best thing about the cookbook is the “Know Your Ingredients” section which offers data about cooking equivalencies. In the Anglo-American world, many know that three teaspoons make a tablespoon and that sixteen tablespoons make a cup. But how many know that the British Imperial Gill (ie the standard measuring cup) holds ten ounces rather than eight? Or that one ounce is sixteen drams? Or that 60 drops equals a teaspoon? Or best of all, that a cup of yogurt serves as adequate substitution for a cup of buttermilk in a pinch. No yogurt? Don’t despair: you can also use a cup of milk with a tablespoon of vinegar.

Skinning a squirrel, Joy of Cooking, 1962

My point here is less about buttermilk than equivalences. They are powerful. Within mathematics, their power is expressed in transitivity relations, the most famous one of which is:

If A=B and B=C, then A=C

But mathematics and cooking are not the only disciplines which rely upon equivalencies.

Western explorers have used equivalencies for centuries. Encountering things unknown, we try to understand them in terms, ideas, and objects of the familiar. Explorers were no different. Darwin’s first glimpse of the Cordilleras in South America made him think of the Andes – mountains that he knew less from experience than from another act of translation: viewing the vertiginous landscapes of J. M. W. Turner.

"Bonneville, Savoy, with Mount Blanc," J M W Turner, 1803

Yet the most powerful equivalencies in exploration were reserved for people. Early Spanish and Portuguese explorers frequently compared American Indians to children: innocent, emotional, lacking in judgment. By contrast, Europeans tended to identify themselves with parental figures: rational, worldly, prudent. This child metaphor proved enormously powerful, creating an equivalency between children and non-western peoples that was used to develop and justify colonial policies through the mid twentieth century.

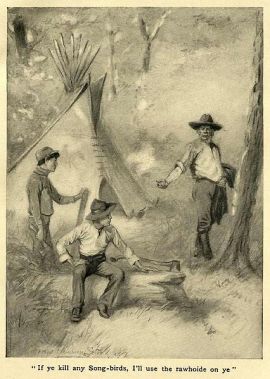

Such was the power of the savage = child equivalency that it spawned new ones. In the early 20th century, Ernest Thompson Seton helped found the Boy Scouts, an organization that put boys in the wild on the premise that if savages are like children, then perhaps children are like savages. The child (or more precisely for Seton, the white child) must pass through a primitive phase before developing into a rational, prudent, moral adulthood. Getting out into nature was not just good exercise, but a way of coaxing young savages into the next phase of their physical and moral development.

Illustration from Two Little Savages by E T Seton, 1903

The child=savage equivalency expanded to include historical (not merely personal) development. If savages were like children, nineteenth century scholars thought, perhaps they represented a child-stage in the evolution of our species. As such, the savage was not merely the equivalent of a child, but a missing link, a living artifact of our earlier history as a species. When Roy Chapman Andrews wrote a book about the “primitive” peoples of the world in 1945, he titled it Meet Your Ancestors: A Biography of Primitive Man.

Roy Chapman Andrews

Others took the equivalency into the human psyche. Freud’s study Totem and Taboo makes comparisons between the behavior of so-called primitive peoples and the neurosis of white adults. Freud’s comparison is based upon the assumption that the human mind carries the imprint of its evolutionary history. That is, humans have an animal mind which has become augmented with the higher structures of the civilized mind. By this line of thinking, the Id is not merely an abstract facet of human psyche, but a historical remnant of our animal mind, an evolutionary calling card from the deep past.

If one accepts (as one shouldn’t) that the child= savage = id = prehistoric ancestor equivalency is true, a number of claims can be made:

- children are useful in understanding primitive societies

- voyages to non-European worlds are voyages back in time

- primitive societies help us understand prehistoric life

- our prehistoric ancestors lived without the constraints of moral inhibition

Yet this set of equivalencies – so powerful in the 19th and early 20th century – has fallen out of favor. Humans do not yield so easily to the transitive processes of mathematics and basic cooking.They are categorically messy, hard to organize, difficult to understand. Perhaps this is best.

Thank God we’ve moved out of that primitive and childlike phase of scholarship!