Guy Waterman

On February 6 2000, Guy Waterman drove his Subaru Impreza to Franconia Notch in New Hampshire, hiked up Mt Lafayette, and in the windy -16 degree night, let himself die of exposure.

Waterman was a man of many gifts and torments, a climber, writer, and environmentalist who lived for thirty years with his wife Laura Waterman off-the-grid in Vermont.

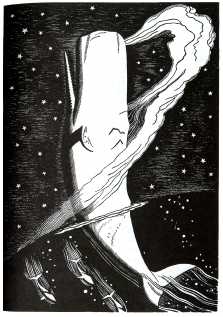

Of these torments, which drove him into deeper and deeper isolation, Waterman said little. Yet he wrote about them through the characters of literature. He was Shakespeare’s Ariel battling the witch-child Caliban. He was Milton’s proud Satan. He was tragic Prometheus. He was Melville’s Ahab.

Prosper and Ariel, William Hamilton, 1797

Ahab. As I read Laura Waterman’s spare, graceful memoir, Losing the Garden: The Story of a Marriage , it seemed an appropriate metaphor for Guy Waterman.

Then, this morning, reading Maria Coffey’s book, Where the Mountain Casts its Shadow: The Dark Side of Extreme Adventure, Ahab surfaced once again. Near the summit of Everest in 1996, David Breashears and Ed Viesturs come across a body near the Hillary Step.

They found [Bruce] Herrod’s body clipped on to fixed ropes with a figure-eight rappel breake. He was hanging upside down, his arms dangling, his mouth open, and his skin black. “Like Captain Ahab,” Breashears later wrote, “lashed to his white whale.” [Coffey, 118]

It made me pause. One hears different many different literary metaphors for explorers and adventurers, but rarely Ahab.

Successful explorers find comparison to Odysseus, the brilliant, cock-sure hero of Homer’s Odyssey. (Confined to the scurvy-ridden cabin of Advance over the long winter of 1854, Arctic explorer Elisha Kane would keep up the spirits of his men by reading them Alfred Tennyson’s Odyssean poem “Ulysses”) Those explorers who perish are commonly portrayed as Icarus, a boy whose joy with altitude overcame good judgment, causing him to fall to earth.

Both of these are figures are imperfect but bright of heart. Ahab is a different creature, a man of darker spirit, a figure turned in upon himself. Ahab’s travels to the ends of the earth bring no discovery or enlightenment; he sees only the white whale. Ultimately his obsession brings tragedy to all, not only Ahab, but to those who follow him.

Is Ahab the true spirit of extreme adventure? You would not think so reading most adventure literature. While these books reveal some of the dirty laundry of expeditionary life, they mostly chronicle struggle and attainment, heroism and transcendence. Indeed, elite climbers often speak of the transcendent moment as the Holy Grail of high-altitude climbing, that thing which brings them back, time and time again, to the most dangerous mountains in the world.

Yet transcendence, going beyond oneself, is the opposite of obsession, a psychic tunneling-in so extreme that it diminishes or excludes everything around it: Golem’s ring, Ahab’s whale, Herrod’s mountain.

Grim metaphors indeed. Perhaps the legions of 8000-meter peak baggers and Seven-Summiters should read Moby-Dick, digest the moral of Ahab, and then turn their attention to the Ahab’s Quaker First Mate Starbuck:

[H]is far-away domestic memories of his young Cape wife and child, tend[ed] to bend him … from the original ruggedness of his nature, and open him still further to those latent influences which, in some honest-hearted men, restrain the gush of dare-devil daring, so often evinced by others in the more perilous vicissitudes of the fishery. “I will have no man in my boat,” said Starbuck, “who is not afraid of a whale.” By this, he seemed to mean, not only that the most reliable and useful courage was that which arises from the fair estimation of the encountered peril, but that an utterly fearless man is a far more dangerous comrade than a coward. [Melville, Moby-Dick]

If this seems too tame or Quakerish for the modern climber, perhaps they’d learn more from a more modern Starbuck, the character Kara “Starbuck” Thrace of the Sci-Fi channel’s Battlestar Gallactica. Thrace is a woman of many demons, of violent appetites. Her thirst for transcendent experience has no limits. But ultimately she channels her dare-devilry into objects of common interest, the search for Earth, the return home.

Kara "Starbuck" Thrace (Katee Sackhoff) of Battlestar Galactica

I’m fairly sure you mean Homer’s Odyssey, right? Aeneas was a wanderer as well, but since the story isn’t quite as iconic, I’d imagine the former before the latter.